When the National Labor Relations Board recently ruled that scholarship-receiving Northwestern University football players were deemed university employees and thus should be able to unionize, I had the strangest reaction, strange at least for a libertarian-leaner who believes everyone should pay less tax.

"If they're employees," I thought, "I hope the IRS sees those hefty scholarship as taxable income."

Even more peculiar: my reaction to preparing our tax folder with all our W-2s, 1099s and receipts. As I sorted and sifted through the papers, I smiled, pleased at the thought of filing our return to the IRS.

Though it's easy enough to explain away my reaction to the football players (it's a justice issue and—I confess—an annoyance, come-uppance issue with spoiled or naïve kids and with opportunistic Big Labor), the smiling at the thought of the IRS is nothing short of evidence of the mighty work of God in my life.

Not that long ago, my husband and I—both self-employed—wrote out checks to the U.S. Treasury on a quarterly basis, and I'd scowl as I filled in the dollar amounts and signed my name, silently cursing this body of government that grabbed so much of our money. In the memo section, right next to the Tax Year, I'd write: "Use wisely."

I'd imagine the eggshell-drab, low-walled cubicles that surely lined the IRS offices. I'd picture the blank faces, inputting numbers, watching the clock. I'd see our hard-earned dollars sucked up by various pork projects, as mere pennies rolled into any worthwhile programs. And I'd shake my head in disgust.

I was rendering unto Caesar like a good American and a good Christian, but I resented every moment of it. Right up till the moment when I went to write a check for our taxes and—gulp—realized I couldn't cover it.

My husband's business had dried up and shriveled. We both looked for work or more work to cover our ever-mounting bills and deep medical debt. Over time, we eventually depleted our retirement accounts, all built on pre-tax money. With every bit we drew out, our tax bill grew. During that time, the work we had prayed for and had assumed would roll our way in plenty of time to pay our taxes never did. We were broke.

When that tax bill arrived, and I sat staring at my checkbook, breathing heavy with worry, my image of the IRS changed. No longer did I see blank faces in drab confines. Now they were angry, jeering ones in courtrooms and jailhouses. I saw pointed fingers and heard tsk-tsking tongues. I saw myself led off to Alcatraz like Al Capone, wondered if I could hold some sort of IRS Tax Bill Event like Willie Nelson.

When we called the IRS to explain our situation, I couldn't shake the horror of our fate. That night, we spent what seemed like hours on hold, getting bounced through the bureaucracy that is not imagined—but very real—we were met with something other than horror, than pointing fingers, than the anger. We were met with something far beyond what I had ever imagined.

Something that looked an awful lot like grace.

We saw this grace time and again during my family's journey through financial desperation. We learned that blessings rarely look like we think they do—and that help, God's help, comes from the weirdest places. Never did I expect God's help, his undeniable mercy and grace, to come from a bureaucrat, to be blinded by God's glory through the kindness of a tax collector, through the mercy of a Big Wasteful Government and its Very Patient Payment Plan.

And yet, this is the odd economy of God's grace. It's upside down; it makes no sense. It never has. It didn't make sense when Jesus extended an arm, offering company and compassion to that tax collector in the tree, when he invited himself to Zacchaeus' house for dinner. And it makes no sense when that tax collector extends compassion and kind words to the broke family on the phone.

But there it is: nonsensical grace in action. Though of course, the grace Jesus offered wipes slates clean, keeps no record of wrongs, and the grace the IRS offers keeps it all neatly tallied and sends reminders every month, still. We broke folks need to take grace however we can get it.

And now, every month, every statement, I'm reminded of this grace, of God's goodness, of the answer to my prayers when I offered up our tax bill and asked for his help. And it's made me—gasp—love the IRS. Now when I write my check, I not only don't scowl, I can't not smile. I can't not pray for the person sitting in that cubicle—whether its painted Eggshell Drab or Glory of God Gold. And I can't not write, as dorky as it may seem, "Thanks for your grace" in the memo line, right next to the tax year.

I still don't like thinking about how much of any of our tax dollars are wasted. I'm still not a fan of Big Government. But I am a fan of the Big God who's always used the unusual, the unexpected and the highly unlikely for his Big Work.

This post is inspired by Caryn's recently released book, Broke: What Financial Desperation Revealed About God's Abundance (IVP, 2014), available on Amazon. Visit her at www.carynrivadeneira.com.

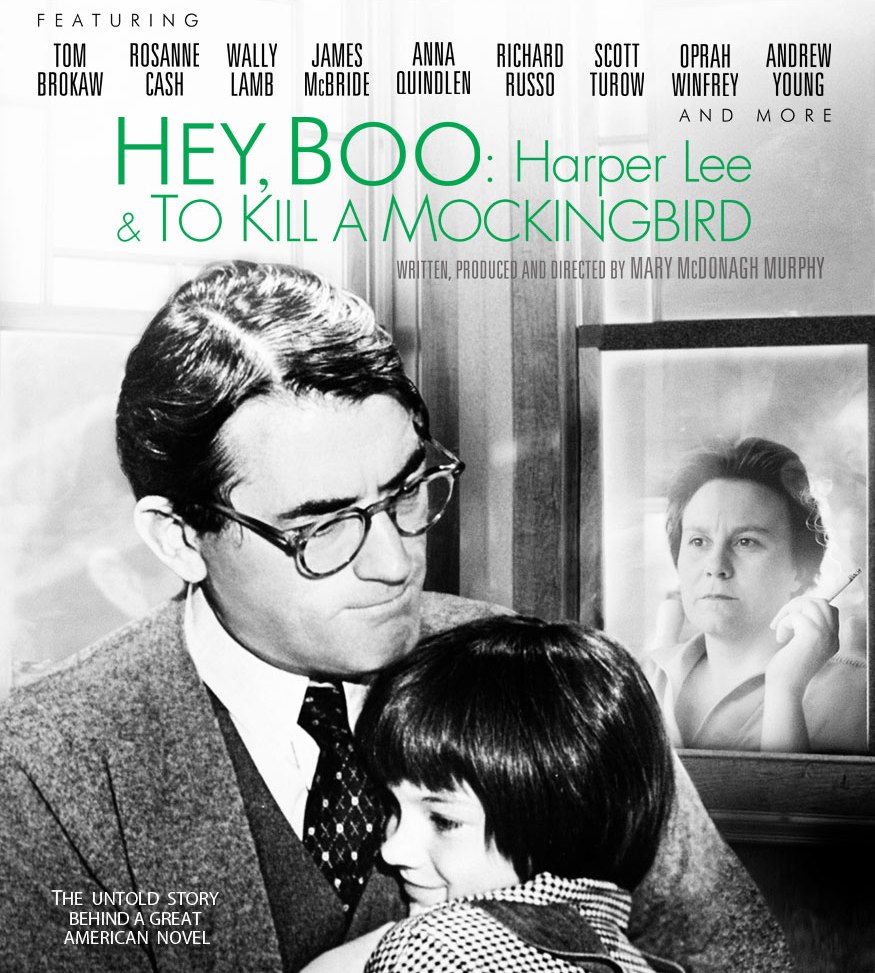

Mary Murphy’s Hey, Boo: Harper Lee and ‘To Kill a Mockingbird,’ which opens in limited theaters this week, is more celebration than investigation . . . and I’m perfectly fine with that.

Few works in the history of American literature are more universally beloved than Lee’s bildungsroman. Add to the novel’s immense popularity the fact Richard Mulligan’s film adaptation consistently tops lists of fan favorites and the task of a documentarian covering this material is simultaneously daunting and alluring. Finding people willing to talk about what the book means to them is seldom a problem. Harnessing that enthusiasm to deepen the appreciation of the work about which every reader thinks he is an expert can be a difficult task indeed.

The key to Hey Boo‘s success lies in director Murphy’s ability to balance critique and appreciation, providing both historical and biographical context – including insights into Lee’s friendship with Truman Capote, and how that plays into the story and the film – to explain the novel’s importance and testimonials to attest to its timeless qualities. Lee Smith, Scott Turow, Oprah Winfrey, Tom Brokaw, and James McBride read from and express admiration for Mockingbird, and, for the most part, eschew the temptation to use the forum to try to make themselves look smart, keeping the focus on Lee’s work.

That’s not to say that the film is superficial. It has plenty of insights for people who know the novel, not just for new fans. Two elements stood out upon reflection. Murphy chronicles how Lee worked with her publisher for approximately two years after the book manuscript was accepted, honing, polishing, and revising the text. Fifty years later, it’s a lot easier to get one’s work into print – but has this relative freedom led to a decline in quality? It’s hard to imagine a book from an unknown artist getting that kind of detailed attention today, and by and large we tend to buy into the Romantic notion that masterpieces are fully-formed offsprings of the minds of creative geniuses rather than hard polished products of sweat equity.

The other element of the documentary that is truly enlightening is Murphy’s putting the novel in its historical context. The further we get from the civil rights movement of the 1960s, the more we tend to misremember To Kill a Mockingbird as a postscript rather than a preface to it. Written in the late ’50s and published in 1960 (the film adaptation was released in 1962), Mockingbird often doesn’t get the credit it deserves for speaking out against racism before doing so was fashionable in white America.

Several of the white interviewees speak out about the complicated, at times even subversive, cultural work performed by the novel. If, as Shelley said, the imagination is the moral instrument, then the book instructs us how to read it when Atticus tells Scout that we must walk in another man’s shoes to truly understand his point of view. For many of us, Tom Robinson’s shoes were the first we walked in that belonged to a man of a different color. Once we took Atticus’s advice, it was hard, if not impossible, to go back to the old ways of thinking.

Here’s the trailer for Hey, Boo:

This review originally ran on Ken Morefield’s 1More Film Blog.