In America, I mocked politicians who plundered for votes by shaking hands and plopping kisses on baby’s plump cheeks. Who do they think they’re fooling? Now, after more than a decade of working in Sudan and South Sudan, I’d take those friendly baby-kissing politicians in a heartbeat.

In a region where armed forces drop bombs on the sick and helpless, the leaders don’t clean up their acts and put on a smiling face for elections, which took place last week in Sudan.

President Omar al-Bashir and the governing National Congress Party declined dialogue with the opposition, and he has shown no sign of ceasing the kind of violence that resulted in a 2009 indictment by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for allegedly directing a campaign of mass killing, rape, and pillage against civilians in Darfur. He’s the first sitting president to face such charges.

Al-Bashir has continued his bombing campaign against the rebels, who say their recent offensive is an effort to support election boycotts. Verified attacks in February and March killed 10 people and injured 61 more, including 16 children.

I recently returned from a month-long trip to the Nuba Mountains region of Sudan, where the organization I lead, Make Way Partners, supports an orphanage for 450 children. In my 30 days on the ground, we only had three without bombs.

The day before I left, the kids gathered to sing one last round of songs to celebrate our time together. When they finished, they waited for me to give a final address, reminding them to obey their teachers, do their lessons, and open their hearts to the goodness of God.

Just as they settled down under their school tree to sit and listen, they shot right back up, whirring past me like dervish dust devils. I hadn’t even detected the sound before their stampede, but in the distance, the thunder of Antonov AN24s rolled toward us. The planes sucked up the blue space of sky over our orphanage.

I helped four-year-old Kaka up from being trampled by the bigger kids. I spotted 10-year-old Rabi, whose right leg was blown off by one of these same machines the year before. His single crutch propelled him up the hillside. The staff directed each child into a foxhole, where we stayed as Antonovs circled us for more than an hour.

When they passed out of sight, we called the children out to take shade under nearby trees. When the planes returned, we didn’t have to tell them to dive back in, the thunder told them for us. We had no water, and the 130-degree heat took its toll.

During one respite under a mahogany, a student nuzzled into my lap. I said, “Welcome, Commander Abdel-Aziz.” He smiled. While collecting child-sponsorship information, he told me, “When I grow up, I will be like our high Commander Abdel-Aziz, and I will kill Bashir and all his people like he is killing ours.” In their region, nearly 1,000 bombs were dropped on civilian targets at the start of 2015 alone, according to local reports.

The next day, the school’s headmaster said his goodbyes. “May you make your journey home safely. I am glad the Arab bombings were not so bad or many while you visited with us this month.”

“But Abdallah,” I told him, “they bombed us every day except three! What do you mean, ‘Not so bad’?” Based on experience, he believed al-Bashir would use heavy bombing to prevent the Sudanese from coming out to vote.

“It’s not possible that I hide in the mountains from airstrikes, Antonov bombers, and then go and vote,” one resident told The Guardian. “What if a citizen goes to cast his vote and gets hit by a bomb? Who is accountable for this citizen’s safety? That’s why there is no such thing as elections here.” News reports, however, attribute the low voter turnout (about 30-35 percent) to either political cynicism or boycotts by opposition.

Shortly before Etty Hillesum was killed in a Nazi Concentration Camp, Dr. Carol Lee Flinders tells us she came to believe, “If she could look straight in to the eyes of the eight-months pregnant wife of an epileptic man who was being transported to Poland, and if she could then look that same day, and just as unwaveringly, into the eyes of the bully who was pushing him onto the train…and if she could then still swear that life is meaningful, then and only then, she maintained, would her words carry weight.”

I cannot yet say that I abide in that sort of love. I know it to be the abundant life Jesus promises us, but the cost is steep: letting go of our comforts and surrendering all the things we don’t understand. I wasn’t able to see the eyes of the pilots flying bomber planes, nor the president who sent them, but as I locked eyes with little “Commander Abdel-Aziz,” I asked God to make room in the inn of my heart for all of them.

Kimberly L. Smith is the president of Make Way Partners, the only indigenously operated relief organization in [North] Sudan and South Sudan providing anti-trafficking efforts to the most vulnerable orphans and former slaves. Smith is also the author of Passport through Darkness, which chronicles much of her experience in Sudan.

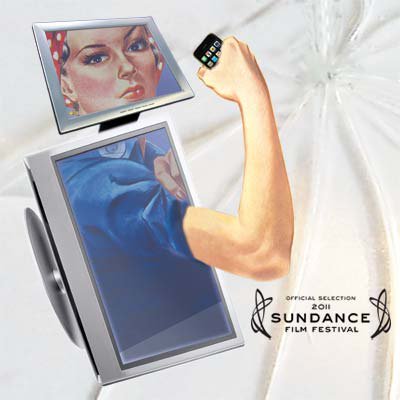

Jennifer Siebel Newsom’s Miss Representation highlighted a group of strong, nuanced, and thoughtful films at the recent Women’s Film Festival in Brattleboro, Vermont. A compelling, persuasive argument about how the media shapes cultural attitudes toward women to the especial detriment of girls, Representation avoids partisan politics—Condoleeza Rice and Nancy Pelosi both appear. It deftly mixes personal testimonies from women in the entertainment industry, interviews with academics and social policy makers, and young people who talk candidly (and often heartbreakingly) about how it feels to grow up in a sex-saturated culture.

Two short films, Angel for Hire and Eggs for Later, deal with the moral implications of fertility technology. Partially a biographical sketch of Noel Keane, the Michigan lawyer who drafted the first surrogacy contract, Angel is most interesting when it shows how implicit conflicts of interests between the prospective adoptive parents (who prioritize the life and health of the unborn child) and the surrogate mother (who may prioritize her own financial and health interests) when complications arise in a surrogate pregnancy. Eggs is a bit more introspective, in part because Marieke Schellart is both documentarian and subject. Thirty-five and single, Schellart hears of a new technology that allows women to harvest their own eggs and freeze them for later insemination and implantation. While most of Schellart’s friends and family are supportive of her attempts to extend her fertility window, her father raises questions and concerns that she struggles to answer. Even if science could enable her to become pregnant after she has stopped ovulating, has she considered the consequences of pushing back not just pregnancy but motherhood?

In America, I mocked politicians who plundered for votes by shaking hands and plopping kisses on baby’s plump cheeks. Who do they think they’re fooling? Now, after more than a decade of working in Sudan and South Sudan, I’d take those friendly baby-kissing politicians in a heartbeat.

In a region where armed forces drop bombs on the sick and helpless, the leaders don’t clean up their acts and put on a smiling face for elections, which took place last week in Sudan.

President Omar al-Bashir and the governing National Congress Party declined dialogue with the opposition, and he has shown no sign of ceasing the kind of violence that resulted in a 2009 indictment by the International Criminal Court (ICC) for allegedly directing a campaign of mass killing, rape, and pillage against civilians in Darfur. He’s the first sitting president to face such charges.

Al-Bashir has continued his bombing campaign against the rebels, who say their recent offensive is an effort to support election boycotts. Verified attacks in February and March killed 10 people and injured 61 more, including 16 children.

I recently returned from a month-long trip to the Nuba Mountains region of Sudan, where the organization I lead, Make Way Partners, supports an orphanage for 450 children. In my 30 days on the ground, we only had three without bombs.

The day before I left, the kids gathered to sing one last round of songs to celebrate our time together. When they finished, they waited for me to give a final address, reminding them to obey their teachers, do their lessons, and open their hearts to the goodness of God.

Just as they settled down under their school tree to sit and listen, they shot right back up, whirring past me like dervish dust devils. I hadn’t even detected the sound before their stampede, but in the distance, the thunder of Antonov AN24s rolled toward us. The planes sucked up the blue space of sky over our orphanage.

I helped four-year-old Kaka up from being trampled by the bigger kids. I spotted 10-year-old Rabi, whose right leg was blown off by one of these same machines the year before. His single crutch propelled him up the hillside. The staff directed each child into a foxhole, where we stayed as Antonovs circled us for more than an hour.

When they passed out of sight, we called the children out to take shade under nearby trees. When the planes returned, we didn’t have to tell them to dive back in, the thunder told them for us. We had no water, and the 130-degree heat took its toll.

During one respite under a mahogany, a student nuzzled into my lap. I said, “Welcome, Commander Abdel-Aziz.” He smiled. While collecting child-sponsorship information, he told me, “When I grow up, I will be like our high Commander Abdel-Aziz, and I will kill Bashir and all his people like he is killing ours.” In their region, nearly 1,000 bombs were dropped on civilian targets at the start of 2015 alone, according to local reports.

The next day, the school’s headmaster said his goodbyes. “May you make your journey home safely. I am glad the Arab bombings were not so bad or many while you visited with us this month.”

“But Abdallah,” I told him, “they bombed us every day except three! What do you mean, ‘Not so bad’?” Based on experience, he believed al-Bashir would use heavy bombing to prevent the Sudanese from coming out to vote.

“It’s not possible that I hide in the mountains from airstrikes, Antonov bombers, and then go and vote,” one resident told The Guardian. “What if a citizen goes to cast his vote and gets hit by a bomb? Who is accountable for this citizen’s safety? That’s why there is no such thing as elections here.” News reports, however, attribute the low voter turnout (about 30-35 percent) to either political cynicism or boycotts by opposition.

Shortly before Etty Hillesum was killed in a Nazi Concentration Camp, Dr. Carol Lee Flinders tells us she came to believe, “If she could look straight in to the eyes of the eight-months pregnant wife of an epileptic man who was being transported to Poland, and if she could then look that same day, and just as unwaveringly, into the eyes of the bully who was pushing him onto the train…and if she could then still swear that life is meaningful, then and only then, she maintained, would her words carry weight.”

I cannot yet say that I abide in that sort of love. I know it to be the abundant life Jesus promises us, but the cost is steep: letting go of our comforts and surrendering all the things we don’t understand. I wasn’t able to see the eyes of the pilots flying bomber planes, nor the president who sent them, but as I locked eyes with little “Commander Abdel-Aziz,” I asked God to make room in the inn of my heart for all of them.

Kimberly L. Smith is the president of Make Way Partners, the only indigenously operated relief organization in [North] Sudan and South Sudan providing anti-trafficking efforts to the most vulnerable orphans and former slaves. Smith is also the author of Passport through Darkness, which chronicles much of her experience in Sudan.

Pregnancy also plays a key role in Maggie Betts’s The Carrier, the story of Mutinta Mweemba, a Zairian woman who is HIV positive and terrified of passing on her virus to her unborn child. Betts carefully and dispassionately lays out the social and political conditions affecting African women and making it hard for them to protect themselves. Mutinta’s marriage is polygamous; she claims her husband lied about already being married but her parents could not afford to return the wedding dowry. Even as she struggles to keep from passing the disease on to her own child, she faces fears of who will raise her children as one of her husband’s other wives dies of the disease and the other faces an initial diagnosis.

Additional films of note at the festival included Living Downstream, Carol Channing: Larger Than Life, Aung San Suu Kyi: Lady of No Fear, and Jane’s Journey, about anthropologist Jane Goodall.

Kenneth R. Morefield, a CT film critic, is the editor of Faith and Spirituality in Masters of World Cinema (Volumes I & II) and the founder of 1More Film Blog.