From my earliest days in ministry, I’ve been told that when it comes to criticism, I just have to develop thicker skin. The implication is that if pastors could just develop a harder shell, we could better resist the pointed pain of negative feedback, much like thicker skin can resist the puncture of sharp thorns. The pain can’t go as deep if thick skin keeps it at a distance.

Today, 16 years into ministry, I’ve come to the conclusion that thicker skin does not exist. The problem with the metaphor of thick skin is that it provides only two options: (1) Harden ourselves to prevent the pain of criticism, or (2) Remain open to criticism and be destroyed by it. The first option is a form of thick skin that makes us unreceptive to all forms of feedback, including healthy, constructive criticism. The second option means subjecting ourselves to a never-ending onslaught of criticism that inevitably leads to burnout or despair. I tried to will thicker skin for years. It never worked, and I doubt it ever will. Surely there must be a better way.

Under attack

My journey with fielding painful criticism began about a decade ago when I was part of a faith community’s transition from its traditional style of musical worship to a more modern form. This dramatic shift, which included expected changes like louder music, lighting and production updates, and, yes, fog machines, was welcomed by some and frustrating to others. It was the kind of shift that produces new-parent levels of sleep deprivation for pastors. And it produced some unsurprising feedback: The music’s too loud. The songs are unfamiliar. The staff is too trendy.

But what was truly painful were the moments when the criticism turned into attacks on people’s character or their faithfulness to God. For some who were unhappy, it wasn’t enough to disagree—their comments had to be underwritten with pseudo-theological justifications.

We were faced with a challenging question: How do we lead a church through dramatic change in a way that honors the voices of those most affected by it and honors the vision God has given us? It’s a crucial question that relates to many situations pastors face: How do we listen well yet maintain conviction? How do we discern legitimate input from reactivity? What’s necessary to create a healthy church culture around criticism and feedback?

In that worship-style transition, I began a journey of discovering that the answer to all these questions actually involves receiving more feedback and hearing more criticism, not less. For the first time, I began to understand that handling criticism well had less to do with developing a thicker shell and much more to do with the structure of our church and its rhythms for healthy feedback.

Feedback from the flock

We all have those critical voices in our churches whom we dread seeing because they seem to always have “feedback” for us. Pastor and leadership coach Steve Cuss refers to these sorts of people as the “usual suspects.” We can’t say we don’t want to hear their feedback because then we seem unteachable or prideful, yet we always feel worse after talking to them.

Meanwhile, other folks in our communities are generally conflict-avoidant and uncomfortable speaking about their concerns. These individuals must get good and mad before they’re willing to speak—so by the time they start giving feedback, we find ourselves on the explosive end of a year’s worth of bottled-up frustration! By that point, without our being aware of it, the relationship has likely already corroded so far on their end that it’s nearly impossible to recover.

The good news is that developing good habits and rhythms for feedback in our churches can help with both of these challenges. In the first case, it can provide a channel for the critical voices in our congregations. This protects pastors from being blindsided by criticism and provides us with a specific context in which we can be mentally and emotionally prepared to receive it. And in the second case, these channels become invitations and natural reward systems for sharing feedback before it gets to an explosive level.

When we create multiple feedback channels and normalize this sort of back-and-forth, we are not just creating a system—we are communicating a posture of humility. This encourages congregants to give feedback before the relationship suffers, and it enables a church’s leaders to benefit from the wisdom of their community. Though there certainly are some exceptions, most feedback begins as a desire to strengthen what these individuals already love to be a part of, not to destroy what they no longer want to see in existence. Consistent, healthy feedback rhythms in churches enable pastors to respond better to criticism personally and congregations to benefit organizationally.

Listening sessions

During all the challenges of 2020, like many churches, we found ourselves facing painful conflicts. A number of folks close to me decided to leave our church or found themselves intensely frustrated. Many talked of their concerns directly with me—which was preferable but also more painful. It was easy to feel misunderstood or to feel like others didn’t recognize the challenge of the moment for church leaders. However, as I reflected on these conversations, the common denominator was the sense that people did not feel heard in our church; hence, they did not feel at home in our church.

One of the hallmarks of listening well is the ability to keep the focus on the person who is vocalizing his or her perspective. The challenge with receiving criticism is the instinctive urge to turn the focus back to us, usually by attempting to defend ourselves. In church (and in relationships in general), feedback conversations go poorly not just because people leave feeling disagreed with but because they leave feeling unheard. Making people feel heard is directly related to our ability to receive—to truly hear—feedback. In this light, James’s admonition calls for a high level of relational intelligence: “Be quick to listen, slow to speak and slow to become angry” (James 1:19).

As a result of studying resources and techniques for listening well, our church developed listening sessions in which church leaders sat down with members of our community, and our only role was to ask questions around contentious topics and then listen and take notes. We weren’t there to challenge, question, critique, or even respond. We simply listened and asked clarifying questions in an attempt to communicate a desire to hear. We found these sessions extremely helpful in creating space for people to communicate their perspectives on a whole host of things, and for us as a church leadership team to grow in listening nondefensively.

Skip-level meetings

I first heard of skip-level meetings on The Andy Stanley Leadership Podcast. Essentially, they are feedback conversations in which leaders at one level of an organization skip one level or more of leadership below them to gather input. In our church, our elders are above me positionally, so they “skip over” me and seek input from team members who report directly to me. These conversations are used to gather feedback on the staff culture and experience, including how I can better serve and lead my team, what areas lack clarity, unique challenges they are experiencing, and anything else the elders might find helpful for serving our staff and church.

Skip-level meetings allow the elders to accomplish two things: First, they’re able to get more candid, honest feedback from each team member (because the person isn’t being asked to give it directly to his or her boss). Second, the elders can hear the feedback as it is given rather than through my interpretive filter. After several skip-level conversations, the elders then take the information they have gathered, extract the areas for growth, and report them to me (with anonymity). This process frees team members from worrying about how their feedback will affect our relationship or endanger their jobs. It also frees me to hear the feedback through the filter of how I can improve, and not of “What does this person think about me?”

But the greatest payoff of all is the cultural one. This feedback tool helps team members feel their perspectives are valued and welcomed, they have a voice, and they have an avenue through which to communicate their needs or concerns.

Skip-level meetings were extremely beneficial as we returned to regular weekly, in-person services in 2021. Our church was losing a lot of volunteers early in that process, so I initiated some skip-level meetings directly with the volunteers to understand why. In the feedback gathered from both those who had quit and those who were still serving, the frustrations they shared ranged from disorganization of supplies, lack of planning ahead, and an overuse of the same people over and over (due to a shortage of volunteers) to insufficient training, inconsistent communication, and a chaotic, hurried experience as a portable church.

From these conversations, we were able to distill the most important priorities and put together a plan of action for improving the experiences of our volunteers. Most importantly, though, the process communicated to them, We are listening, we care about your experience, and we are working to improve it.

Quarterly assessments

A third tool I’ve used for gathering feedback is quarterly assessments. Since we did not want to create a culture in which one person’s value was directly connected to his or her performance, our staff initially resisted such tools. Yet as I discovered the need to receive better feedback, I reconsidered assessments, and we’ve since made them part of our staff’s rhythm—but with some crucial modifications.

First, and most importantly, in a culture of healthy feedback rhythms, I know it’s crucial that I be subject to an assessment myself (instead of just other staff members). Second, we incorporate a self-assessment as part of the process. I find this very helpful in my pastoral ministry. In the self-assessment, I answer the same questions about myself that our elders (my bosses) will be answering about me. This infuses the whole process with a bit of humility—if I am honest with myself, it’s unrealistic to expect to get perfect marks on everything. It prepares the way so that when we come together for a conversation, I am ready with thoughts regarding my own areas of needed improvement and I’m also in a posture of humility to receive their feedback. This makes those conversations much less personal and much more constructive.

More, not less

The secret to dealing with negative feedback isn’t to try to develop some mythological skin impervious to the emotional puncture of criticism. It’s absurd to think we pastors could somehow receive negative comments about us, our performance, or our leadership and never be hurt by them personally. That’s a lie we have somehow perpetuated on and on, simply because it sounds good. But it’s time to acknowledge the truth: Thick skin is a myth.

However tempting it may seem, the secret to dealing with criticism as pastors isn’t to avoid it or hear less of it. The secret to handling criticism well is to create channels and practices that allow for more of it, but in healthier ways. Of course this won’t entirely remove the sting of criticism, and it won’t remove the critical spirit of an individual in our flock. But healthy feedback tools do provide less-personal pathways for this communication to take place so that we, as leaders, can remain humble, teachable, and receptive to wise counsel without being destroyed by the emotional blows that often accompany it.

Ike Miller is the author of Seeing by the Light and lead pastor of Bright City Church in Durham, North Carolina. He holds a doctorate in theology from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School.

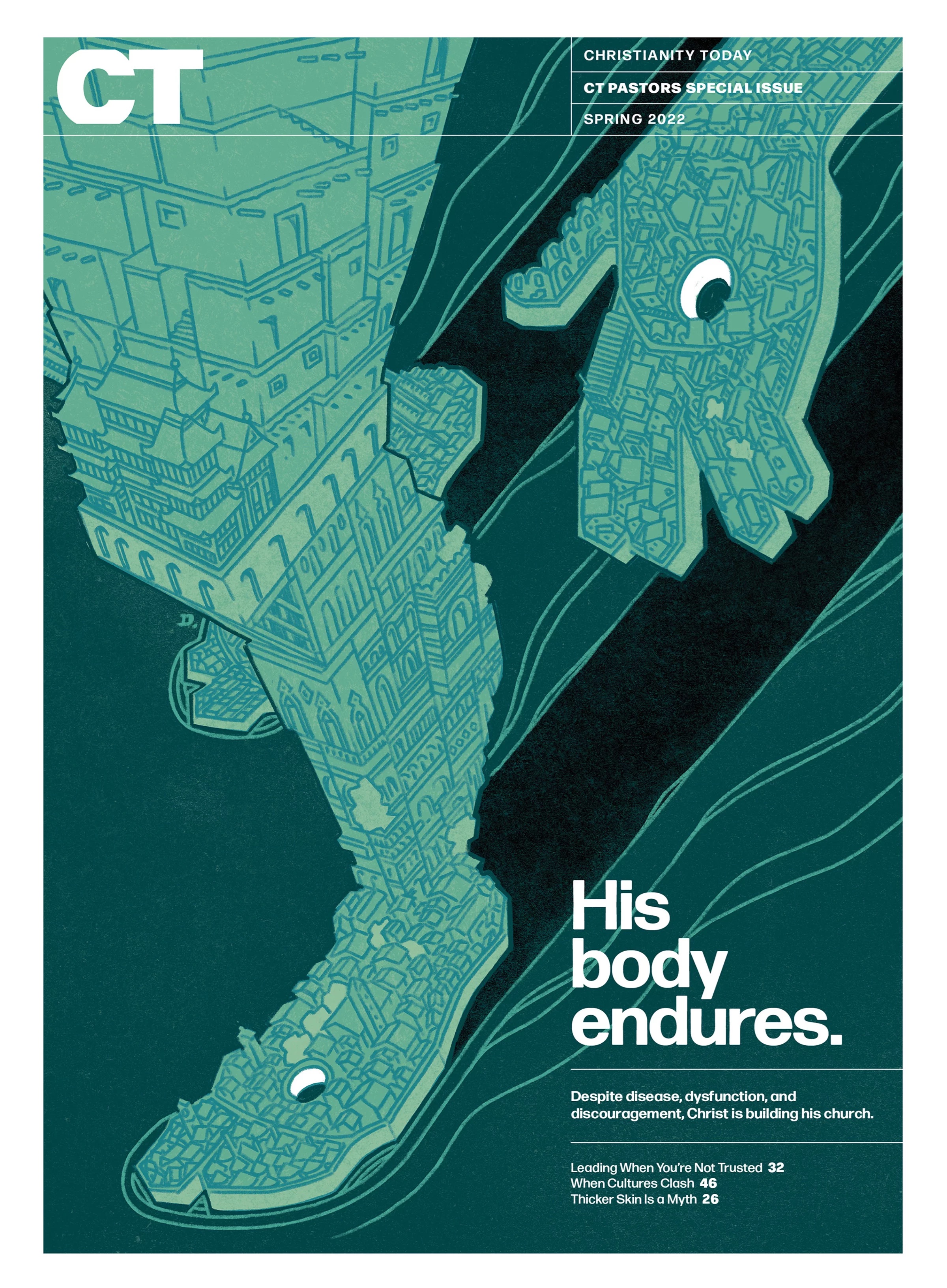

This article is part of our spring CT Pastors issue exploring church health. You can find the full issue here.