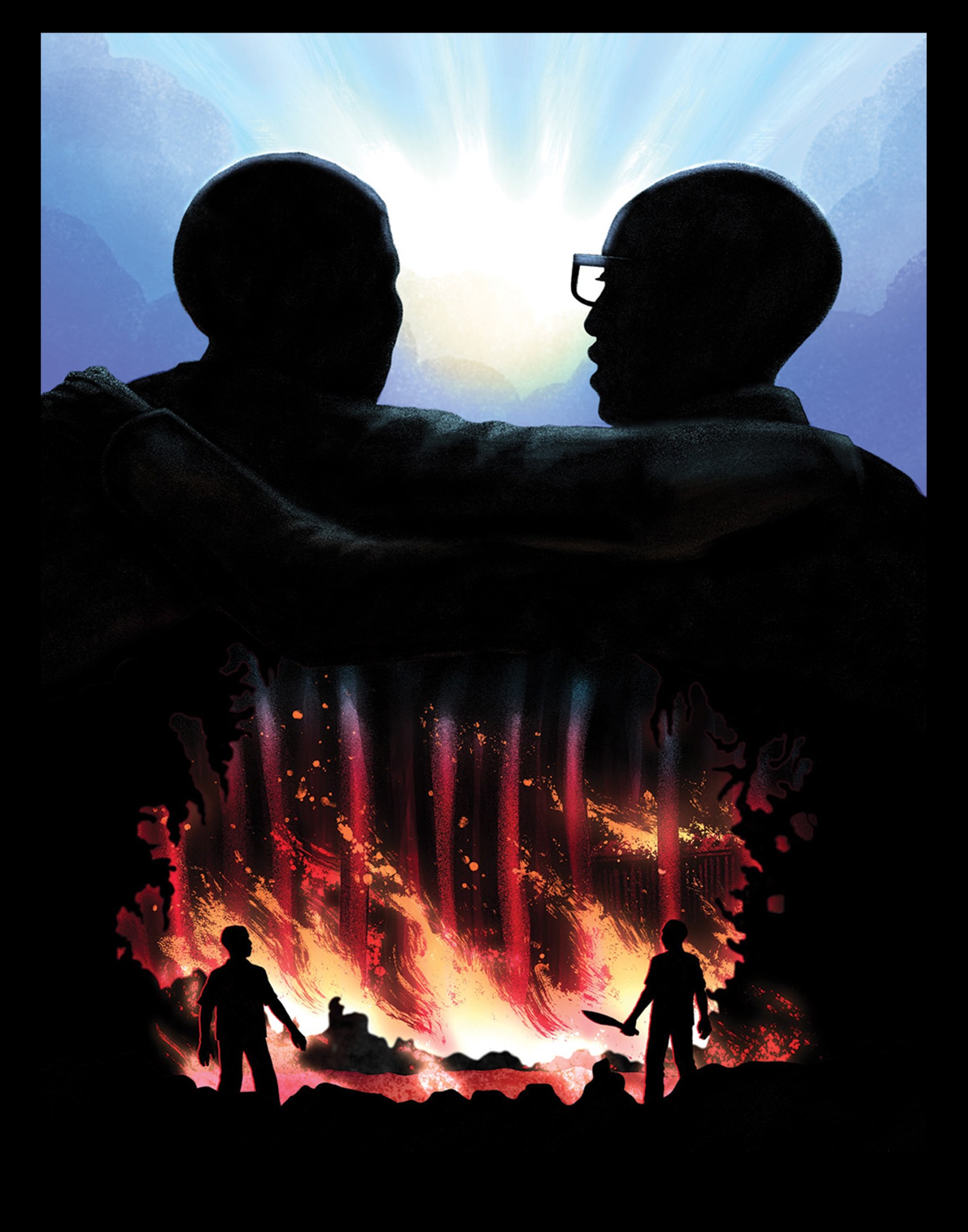

Gahigi Stephen and Sendageya Matias were once neighbors in a small village near Rwanda’s border with Burundi. Stephen, a Tutsi, is tall and slender with a broad smile. A pastor, he had a wife and children and a small farm where he raised cows.

Matias, a Hutu, has widely spaced dark eyes, a humble manner, and a ready smile. He and Stephen were friends. Once, when the pastor saw that Matias was in need, he gave him a cow—a gift that provided milk, manure for crops, and extra income.

In April 1994, Stephen knew that something terrible was going to happen. He had heard about killings in other areas. In the rural countryside, the machetes had all been sharpened.

Stephen and his family fled their home. If they could only get to the border with Burundi, perhaps they’d be safe. They and other Tutsis from the village ran through fields of sorghum, pushing through thick jungle bushes in the night. As they neared the border, there was a burst of gunfire. Stephen saw friends and neighbors running one second and then punched down by bullets the next, lying still in the dirt. Stephen and his family were surrounded. He saw Matias, his Hutu neighbor and friend in the darkness, a machete in his hand. The man’s face did not look right.

“I was filled with hate,” Matias says now. “The government supported us; they told us to go and kill. The district officials told us to get going, do your work, massacre them all.”

Matias was 37 at the time. He felt like Satan was twisting his mind. “I was in a terrible state. I would kill people and take their clothes. Even the women we found dead, we would take their clothes.

Illustration by Matt Williams

Illustration by Matt Williams“I went to Pastor Stephen’s family with so much hate. I wanted to do harm even though he had given me a cow. I killed the rest of his cows. I killed six of his family.”

In the chaos of that horrific night, after Stephen recognized his neighbor among the angry mob, the pastor became separated from his family. He ran again through the bush. He heard a child crying. He stopped. In the dim light he could see a boy, about four years old, whimpering near the base of a tree, blood all over him.

“My heart!” Stephen says with tears even now, three decades later. In his confusion and terror, he had almost not recognized his own son. He rushed to the tree and knelt in the dirt. He whispered to the child, “Who am I? Who am I?”

“Papa!” cried his son.

Stephen scooped up his only surviving child and ran and ran and ran. He and his son made it to Burundi.

In 2024, Rwanda marked the 30th anniversary of its genocide, which began after assailants shot down a plane carrying the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi. Rwanda’s Hutu-led government blamed the crash on Tutsi rebels, unleashing a campaign of systematic killings of Tutsis. They used machetes, guns, and clubs to kill 800,000 people in 100 days.

“Rwanda was completely humbled by the magnitude of our loss, and the lessons we learned are engraved in blood,” President Paul Kagame said at an April 2024 ceremony.

When the genocide was over and almost a million people lay dead, Stephen returned to his village. Matias was arrested and thrown into prison, along with tens of thousands of his fellow perpetrators.

Stephen had survived. But each day was excruciating for him. “How could innocent people be killed like this?” he says. “I was full of hate. I didn’t want to see or hear people like Matias. So much pain. In Rwandan culture, men are not supposed to cry. I had my life and my little son; I was lucky. But I had lost everything else. My wife, my other children, my aunties, my parents, my sisters. I was hungry. I was poor. Nothing!”

It was hard to pray. When Stephen did, pouring out his pain to God, there was only silence. Then one night Stephen felt God say to him, “I want to take away your pain. I have preserved you to use you. I want to use you to show my glory.”

Stephen wept and punched his fists in the dirt. He sobbed all night. Then, impossibly, in the morning he began to feel rest. “I began to feel a new mind,” he says. “Christ, on the cross, said, ‘Father, forgive them, they don’t know what they’re doing.’ My boss Jesus Christ went through this. I began to take small steps.”

In taking those steps, Stephen discovered that forgiveness could mean life for him. Without forgiveness, he would spend the rest of his years in a bitter monotony of mental torture and anger. And if Christ had the power to forgive, then surely he would share that power with Stephen.

It wasn’t merely an internal mental or spiritual process. Forgiveness required small, active steps—doing what Stephen perceived God was telling him to do.

So the pastor went to preach the gospel at the stinking, overcrowded prison where Matias and other killers were behind bars. When Matias saw the pastor in the crowd in the prison yard, he hid. He knew Stephen had come to kill him. And he understood why.

Photo courtesy of ICM

Photo courtesy of ICMStephen did find Matias. He told him a few simple facts. Because of Jesus, Stephen told Matias, he had forgiven him for killing his family. He told Matias that if he repented, God would forgive him. God could make him new.

No. Matias couldn’t believe it. Too good to be true. Impossible.

But eventually, Matias began to believe Stephen’s sincerity, and the power of his forgiveness helped him believe his message. He confessed his crimes to God, to Stephen, and to government authorities. He told Stephen where his family’s bodies had been thrown on that dark night years earlier. Stephen found a measure of closure in news that he could bury their remains.

After almost 10 years in prison, Matias was released. He’s in his late 60s now. Most days he meets up with Stephen. “He drives me in his car,” Matias says. “I share food with him. We want to carry this message of forgiveness and reconciliation all over Rwanda.”

They speak to Rwandan groups and visitors to tell their story and show the miracle of their rekindled friendship. Matias speaks simply about the darkness of the past. He doesn’t philosophize. “I was saved. I felt my guilt removed. Now Stephen and I are friends.”

Stephen feels the same way. He says that forgiveness and a desire for reconciliation don’t come from human determination, but from the power of the Holy Spirit.

“After the genocide I had many enemies,” he says. “Now, because I forgave, I have no enemies. And I have a friend. Matias.”

Ellen Vaughn, an author and speaker based in northern Virginia, reported this story from Kigali, Rwanda. Her latest book is Being Elisabeth Elliot.