On a chilly Saturday morning, Hmong women sit in the sun and chat while embroidering and selling their harvest of jicama. In the marketplace behind them, a woman uses chopsticks to flip balls of dough in sizzling oil. A man displays handmade knives atop a wooden box.

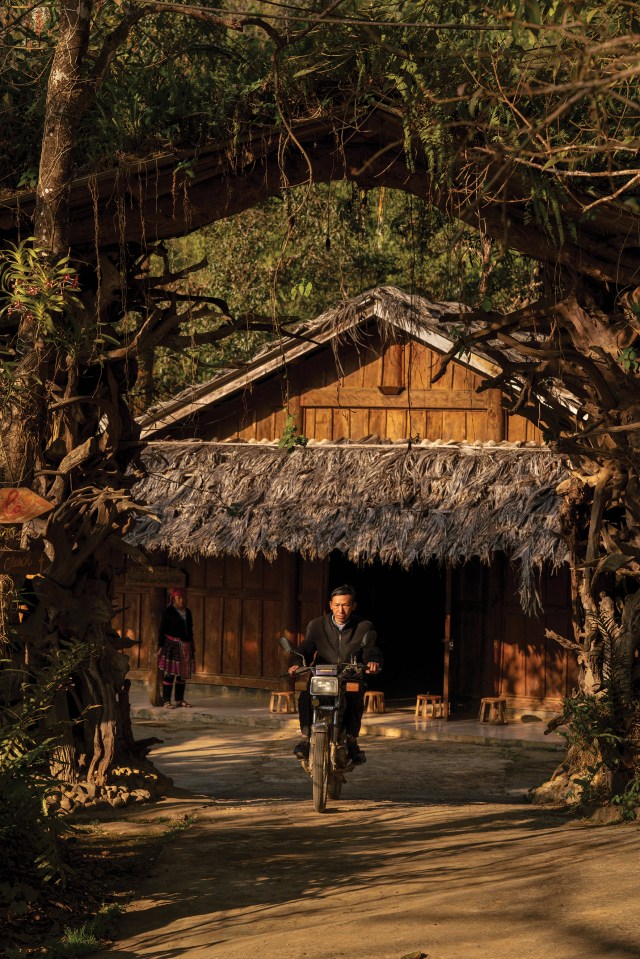

The Hmong village of Sin Suoi Ho, home to more than 100 families in the highlands of northern Vietnam, draws weekend shoppers from nearby Hmong and Dao villages, as well as tourists from the capital of Hanoi. Until just recently, getting here required an 8-hour, 250-mile trip past terraced rice paddies and up winding, teeth-chattering dirt roads that reach high into the mountains.

The shoppers browse stalls filled with colorful hats, bags, and clothing. They examine pillowcases covered with traditional Hmong embroidery. They snap selfies in Hmong dresses and giggle at elaborate silver headdresses. Beyond the market, visitors stroll along a lane lined with potted orchids for sale. They eye young men lashing peach tree branches to motorbikes (the budding limbs will go to another market to be sold as decorations for Tet, Vietnam’s lunar new year celebration).

The tourists come not only for the wares but also to partake in a story of transformation—a story of economic advancement and changed hearts.

Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim BarkerFifty-nine-year-old Chang A Hang is a witness to the change. I find him sitting in a plastic chair outside his store next to the marketplace. Children gripping ice cream cones drop coins into Chang’s outstretched hand. The lines etched into his face and the weary look in his eyes betray the hard life he’s lived.

For much of Chang’s life, Sin Suoi Ho was the poorest village in Lai Châu province. He and his family often lacked rice to eat. Residents grew opium poppy, and Chang, along with most of the village, was addicted to opium. Chang was also one of the village’s 10 shamans, responsible for curing the sick through the spirit world, yet tormented by spirits himself.

In 1992, villagers began hearing the gospel through a Christian radio broadcast. Faith spread quickly, despite government persecution. Chang at first brushed the new religion aside. But everything changed in 1998, when he says that one night he saw a spirit float to the bed where his wife lay fast asleep. The next morning she was deathly ill. Powerless to help, Chang asked the village pastor to come and pray for his wife. She was healed immediately.

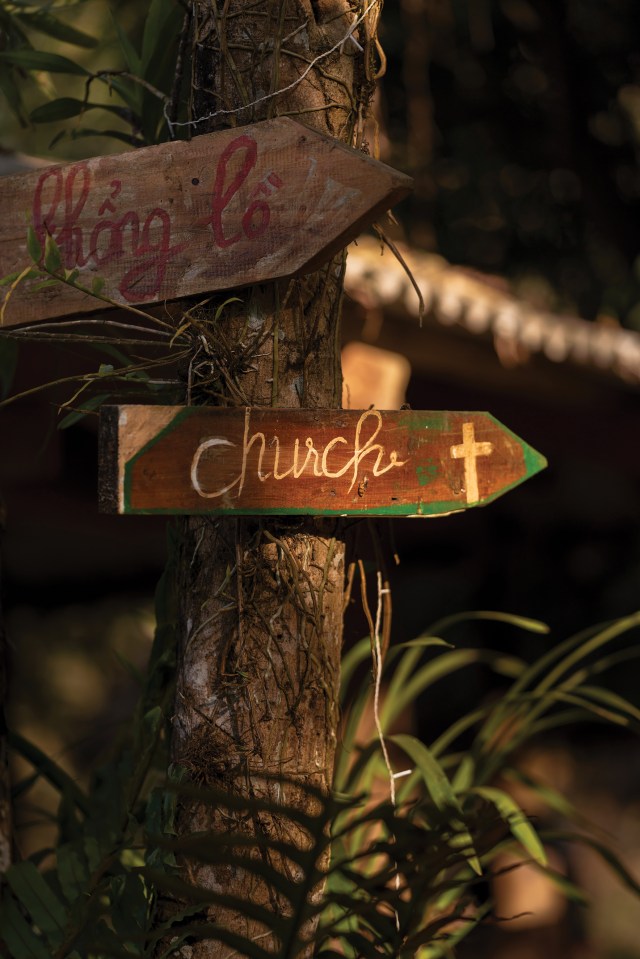

The encounter changed Chang completely; he is now a pastor too, working in a nearby village church. Thirty years later, the majority of Hmong families in Sin Suoi Ho are Christians, save for about 20 families.

For these converts, the gospel has manifested itself not only in personal transformations but in community-wide change. Village pastor Hang A Xa, who prayed for Chang’s wife, taught villagers to apply the Bible to every aspect of their lives. They detoxed from their addiction. They gave up opium cultivation and grew orchids instead. They cleaned up their village and built a road. Because the Bible declared that men and women were equal, parents stopped the practice of demanding prohibitive bride prices, and they allowed young women to complete more schooling.

Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim BarkerAnd against all odds, Sin Suoi Ho became a tourist destination.

Villagers tell their story in religious terms, not economic ones. Across Vietnam, Christian belief has faltered among Vietnam’s majority Kinh population, who possess more of the country’s freedoms and wealth. But in ethnic-minority communities like Sin Suoi Ho—only 11 miles from the Chinese border, in a sensitive region where the Vietnamese government prohibits outside visitors—Christianity has spread.

Vietnamese pastors say the country’s rapid economic growth and the trappings of wealth are obstacles to sharing the gospel in the cities. In hardscrabble places like Sin Suoi Ho, however, the good news can bring beauty, flourishing, and a taste of Eden.

Vang A Chu, the associate pastor in the village, noted that Adam and Eve’s sin forced them out of the Garden. Yet in Sin Suoi Ho, “Jesus has come to earth and now we have freedom.”

“Where we live is Eden,” he said. “And we have to take care of our village.”

The Hmong people originated in China and began spreading to the mountainous areas of Laos, Vietnam, and Thailand in the 18th and 19th centuries in search of agricultural opportunities and to escape persecution from the Qing dynasty.

During the Vietnam War, the United States recruited Hmongs in Laos to help fight against the Communists. Hmong soldiers, led by General Vang Pao, blocked Hanoi’s Ho Chi Minh Trail in Laos and rescued downed American pilots. After the US military withdrew, many Hmongs were targeted by the communist government in Laos, leading thousands of Hmongs to resettle in the United States and other Western countries. Many Hmong refugees converted to Christianity. Their history of resistance led the government in Vietnam to view them suspiciously. Decades of government attempts to resettle, develop, and assimilate the Hmong left them “marginalized by programs that purport to development,” wrote anthropologist Tam Ngo in The New Way: Protestantism and the Hmong in Vietnam.

Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim BarkerForeigners and missionaries had largely fled Vietnam by 1975, but the Far East Broadcast Company (FEBC) continued broadcasting the gospel into the country in minority languages. Beginning in the 1980s, Hmongs in Vietnam started tuning into a broadcast from a Hmong pastor in California who went by the radio name John Lee. Families, then whole villages, came to Christ. The new Christians started sharing the gospel with other Hmong villages.

Initially, Lee didn’t realize the impact his program was having in Vietnam, according to Reg Reimer’s Vietnam’s Christians: A Century of Growth and Adversity. By the late ‘80s he was receiving thousands of letters from Hmongs in Vietnam who had accepted Christ and wanted to learn more about the faith. Today more than a third of the 1 million Hmong in Vietnam are Christians.

Some Hmong villages saw their standard of living improve as they abandoned religious practices that required expensive animal sacrifice and learned to read in order to study the Bible.

Nowhere is the transformation more apparent than in Sin Suoi Ho, now a burgeoning destination for tourists who want to experience “untouched” Hmong life. In the 1980s, the village was no more than a few wooden houses in the jungle. Neighboring communities called it “Opium Village,” yet growing opium was never profitable; it left villagers poor, sick, and addicted.

Former village chief Hang A Lung first came across Lee’s program, Source of Life, in 1992 on a radio gifted to him by local government officials. He kept listening, as it was the only program in his native Hmong language. Soon he was hooked. Speaking in a melodious lilt, Lee incorporated Hmong folktales into his teaching to help Hmongs understand the gospel.

Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim BarkerA Lung was struck by Lee’s declaration that Jesus is the only way to heaven. During the rice harvest that year, he and his family became the village’s first Christians. They burned their altars to the spirits and their traditional burial clothes. “We prayed to Jesus to come into our house,” remembers A Lung’s daughter, Thi Do, who was 13 at the time.

Christians from a neighboring Hmong village came to teach the family more about Christianity and joined them in sharing the gospel with other families. Some, unhappy with Hang’s eagerness, reported them to the authorities.

Fearful that conversion to a “Western” religion would lead Hmongs to resist government power, local officials arrested and beat the new Christians. They confiscated radios, Bibles, and cassette tapes. Thi Do’s husband was beaten so badly that he could only eat rice porridge for weeks. Police held her brother-in-law in a house and tied him to a table. He gnawed through the rope to escape.

At the time, Thi Do said, their faith was so strong that they didn’t think about turning back. Other families joined their number: Villagers came to Christ after miraculous healings or finding freedom from the constant fear of spirits. By 1995, about 20 more families had turned to Christian faith. They started to gather for weekly worship in homes or in the jungle to avoid detection.

Most were still addicted to opium. Some worshipers smoked before and after services. One day while studying Matthew 5:16 (“Let your light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven”), the believers felt the Holy Spirit convicting them to quit. “We had to stop using opium so that we could shine for other people to know about God,” said A Lung’s son, A Xa.

Church leaders brought addicted believers up into the jungle-covered mountains to help them detox. They cooked them meals, massaged their aching bodies, and washed their soiled clothes. To help pass the time, they taught them about God and sang worship songs. When withdrawal kicked in, they stopped them from running back into the village.

Returning to the village at the end of a two-week detox session, most eventually relapsed. But the few who stayed clean led the next group into the jungle. Some returned seven times before they could completely kick the habit, A Xa said.

It took 10 years, but by 2005 every Christian in the village had stopped using opium.

Escaping opium’s grasp was the first step of Sin Suoi Ho’s transformation. Next came breaking the village from cycles of generational poverty.

After deciding to become a pastor at age 20, A Xa went to study the Bible with other Hmong Christians in Yunnan, China, and later in Hanoi, despite having only a primary school education. Each time he returned to the village, he’d teach about the Bible and how it applied to everyday life. He led a small group—the first one in 2005, after which members went on to lead their own. By 2010, 100 villagers were trained to lead house church–like groups.

God called Christians to be witnesses, A Xa taught. So villagers needed to clean their homes and their village. Both humans and livestock shared the village roads. Feces, food scraps, and trash littered the ground. Even inside their homes, chicken and pigs roamed free. A Xa taught them that cleaning their living spaces prevented disease and sicknesses from spreading and was a way to take care of the land God had given them.

“It will be like salt and light to other villages,” said his sister, Thi Do. “They will know about God, that God is good, and that Christians are good, not bad.”

Next, A Xa taught villagers about setting goals and planning ahead, rather than being content with subsistence farming. He taught basic business skills to help them make more money for their labor. He pushed against the Hmong tradition of early marriage, where girls wed as young as 13 and cut short their education. He encouraged parents to keep both their sons and daughters in school.

A Xa also advocated against the custom of marriage dowries. Traditionally, a Hmong man’s family would pay the wife’s family a large dowry, saddling the newlyweds with debt and effectively selling the bride to her husband’s family.

To combat this, A Xa had to lead by example. His own daughter became the village’s first bride to not seek a dowry when she was married. (All three of his daughters graduated from college, another pioneering act.)

Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim Barker Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim BarkerNone of these changes happened overnight. Some villagers protested against A Xa’s ideas. “It’s so difficult to change people’s minds,” he said. “If we didn’t have the Bible, we couldn’t change.”

Another first: Residents decided to grow orchids to beautify the village in 2011. They trekked out to the jungle to find them and planted the orchids outside their homes. Then visitors from around the border region began offering as much as $42 to buy the plants. (Orchids are a common decoration for Tet.)

Sensing opportunity, villagers grew the flowers in earnest, making three times as much from selling orchids as they did their traditional crops. Today in Sin Suoi Ho, the orchids grow in pots and cover off-season rice fields. Growers train them to bloom during the week of Tet, when they fetch the highest price.

By 2012, A Xa and the new village chief, Vang A Chinh, realized the village needed a working road. It would make it easier to transport their rice crops to markets where they could sell it for more money, and it would allow people to visit the remote community.

The two men approached local officials. Would the government provide cement if the village provided its own sand and gravel? The officials agreed, then taught villagers the basic steps for construction. And the people of Sin Suoi Ho came together to build three miles of road.

Next, they opened a Saturday market. To lure customers, villagers put on roadside performances showcasing Hmong singing and dancing, catching the attention of passing motorists. Tourism grew, and the government began holding up Sin Suoi Ho as a model for local development without any outside help.

The persecution of Christians in Sin Suoi Ho gradually eased too. A Xa’s church, which is now part of the Christian and Missionary Alliance denomination, earned official government recognition in 2011.

When they talk about their success, A Xa and other villagers don’t withhold their strategy: “If it was only based on the work of humans, we can’t change,” Vang, the associate pastor said. “Now you can see the village looks beautiful. It’s because we use the Bible for living our life.”

In 2015 the government officially recognized Sin Suoi Ho as a tourist destination, an act that effectively removed government restrictions on outside visitors. That sealed the transformation: A village once persecuted and isolated could now host visitors from across Vietnam and from around the world.

Photo by Tim Barker

Photo by Tim BarkerFamilies opened up their homes to tourists. They set up beds in their living rooms and extra seats at their tables. Those who couldn’t house visitors could sell their orchids, their vegetables, livestock, and handiwork—all at higher prices. They could run herbal baths or rent out Hmong dresses.

By the time the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, Sin Suoi Ho saw about 100,000 visitors a year.

“When I was a kid, I never dreamed Sin Suoi Ho would become a tourism destination,” said Vang A Chinh, the village chief, sitting in the courtyard of his homestay with a creek flowing through a jungle-like garden and outdoor café. “After we became Christians, we learned how to make a plan for our lives and work to follow that plan. God changed Sin Suoi Ho into this.”

The pandemic paused tourism for two years. Villagers focused on growing orchids, cardamom, and rice. They built new bungalows and guesthouses. And they waited for the tourists to return.

Today, the main road in Sin Suoi Ho is clean and paved, running up the mountain past the thatched-roof church framed by an imposing gate made of curved tree branches. A woman dressed in a patterned Hmong jacket and skirt—over sweatpants—talks on her smartphone while a buffalo and her calf feed on a nearby tuft of grass. Further up the mountain, a coffeeshop overlooks the village and beyond—to rice paddies and jagged layers of blue mountains.

The owner of Ka Sha Coffee is A Xa’s daughter, 28-year-old Hang Thi Su. Rather than wearing traditional Hmong clothing, she’s dressed in a fuzzy brown jacket and jeans as she snaps photos for her Facebook account to promote the village. Not only was she the first woman here to sidestep an early marriage and graduate from college, but she was also the first to marry someone who is not Hmong (her husband is Kinh, Vietnam’s largest ethnic group). She is Sin Suoi Ho’s only English speaker.

When Thi Su and her sisters went to college, villagers called them lazy and whispered that they’d lost their way. “But [my father] didn’t care because he knows us, he knows what we are studying and what we are doing,” Thi Su said. “Now parents say, ‘Go to school and be like them.’”

Since returning in 2018, Thi Su has taken to heart her father’s exhortations that tourism doesn’t just help the village financially but is also an opportunity to share the gospel. When tourists visit, she introduces them to time-honored Hmong traditions like handwoven hemp clothing, harvest season dances, or tuj lub, a game where competitors try to knock each other’s giant spinning tops off balance.

But she’ll also tell them about traditions they’ve left behind: flutes and drums used in religious rituals, shamans, and bride kidnappings. She repeats the story of how God brought their village from filth to beauty, from addiction to freedom, from barrenness to bounty.

“Everything we do is for God, not only to make money,” Thi Su said. “I hope we can keep the Hmong culture, we can share our culture with the world, and we can share the gospel through our culture.”

Angela Lu Fulton is CT’s Southeast Asia editor. She reported this story from Sin Suoi Ho, Vietnam.