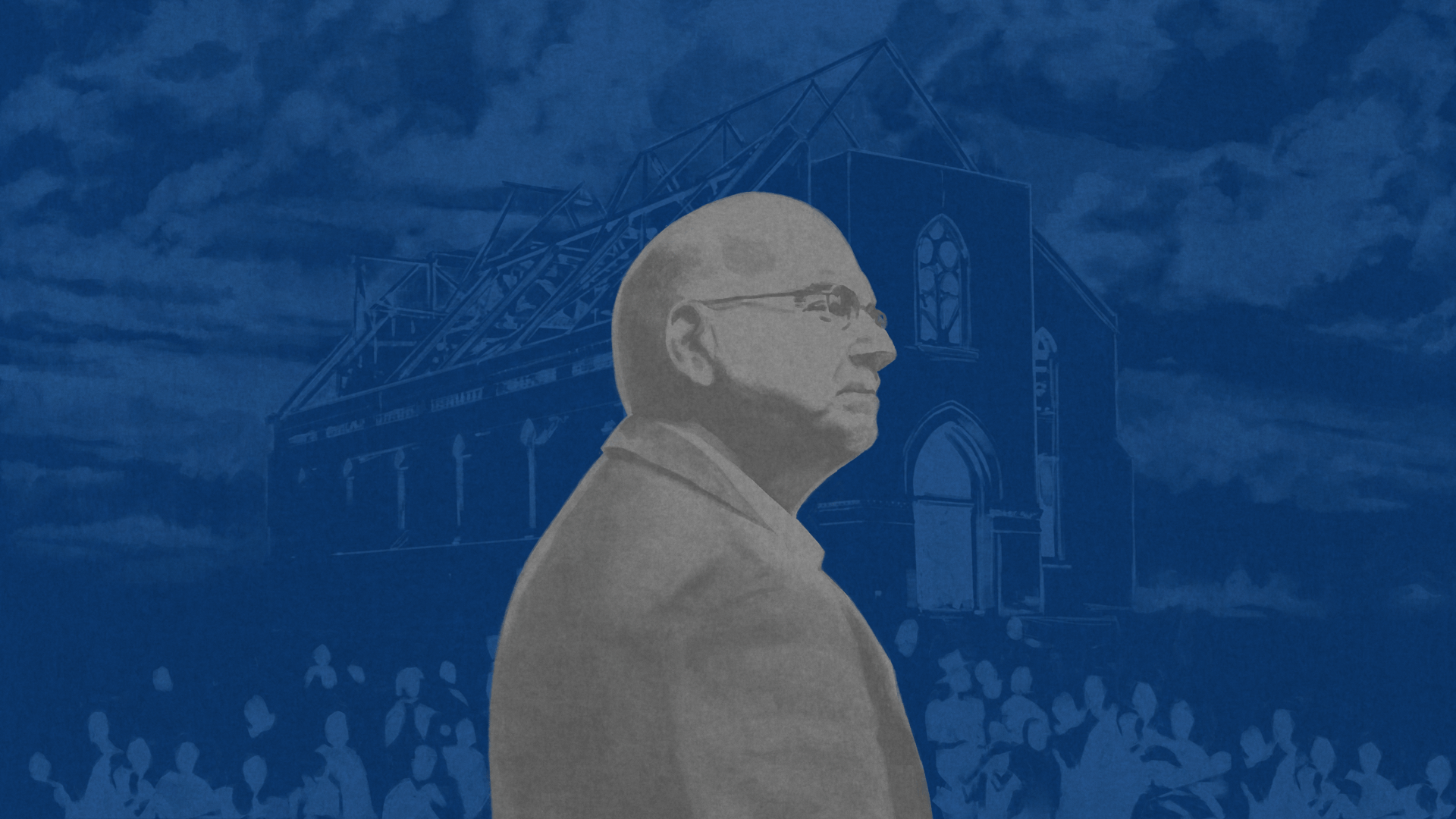

I first met Tim Keller nearly 20 years ago at the inaugural conference of The Gospel Coalition while covering the event for Christianity Today. I had recently written the 2006 CT cover story “Young, Restless, Reformed,” about the New Calvinist resurgence then popularized by figures like John Piper, Albert Mohler, and C. J. Mahaney. Keller became one of the most important leaders in that movement, especially by inspiring church plants in the world’s most influential cities.

But in 2007, Keller was not yet a household name. He hadn’t published his 2008 bestsellers The Prodigal God and The Reason for God. Even then, however, Keller had begun to help Christians navigate the social and academic pressures driving down church attendance, especially in urban areas and universities. Keller was early to recognize this secularizing trend. In the past 25 to 30 years, some 40 million Americans have left the church—the largest and fastest religious transformation in American history.

When Keller died in 2023, he was still working toward a unified Christian response to this shift occurring across nations and institutions, training urban church planters and devising evangelistic strategies. Together, he and I founded The Keller Center for Cultural Apologetics. In annual retreats and online cohorts, we continue to build on what so many learned from Keller, applying an unchanging gospel to an ever-changing culture.

Not everyone agreed with how Keller counseled Christians to engage with this “great dechurching,” though. And the roots of that division go back to the origins of the Young, Restless, and Reformed movement.

At CT 20 years ago, we weren’t just trying to be clever when we described this nascent movement as “restless.” Keller represented a more academic and urban wing of the movement, comfortable in the neo-evangelical institutions where he studied, taught, and published.

But in the 2000s, a more populist wing of this Reformed movement adapted the methods of shock jocks and standup comedians to bring disaffected young men into the church. Other populists criticized denominational leaders as corrupt, out of touch, and lacking in zeal to confront cultural elites, largely through partisan political activism.

This populist-institutional divide has widened, especially as the United States continues to move away from Christianity. And the not-so young and Reformed remain restless, often directing their ire toward each other.

Keller lamented these divisions. He didn’t dwell on them, however, even as they intensified near the end of his life. He remained focused on the same evangelistic projects that had occupied him since moving to New York City and planting Redeemer Presbyterian Church in 1989.

Keller was the first to insist that his ideas weren’t novel. The Bible and historical Reformed confessions directed his teaching, from his start as a small-town pastor to his legacy as one of the most globally well-known evangelical preachers. When looking to the future, Keller looked backward for guidance.

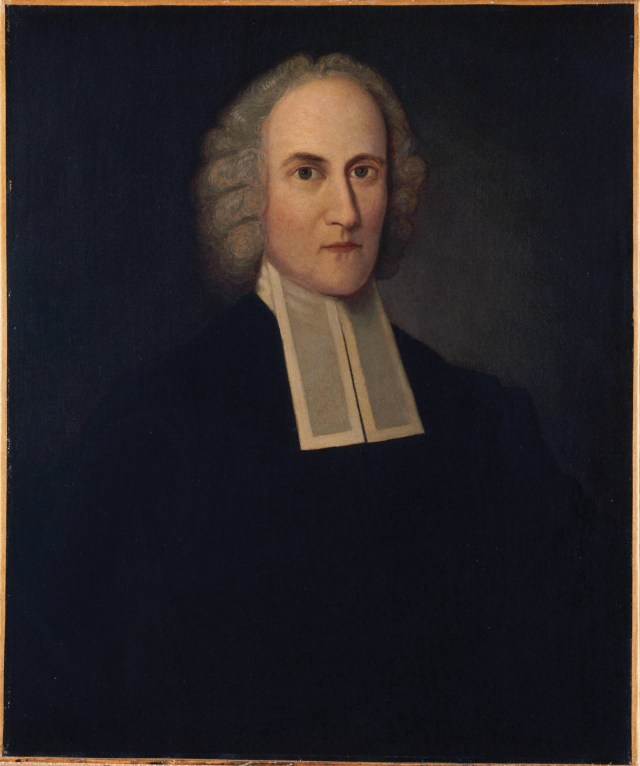

When he cofounded The Gospel Coalition in 2005, he lamented how evangelicalism had declined since the previous generation of leaders like Francis Schaeffer and John Stott. Reaching back even further for a model of maintaining orthodoxy amid modernity, Keller turned to one of the most influential pastors in American evangelical history, the 18th-century New England revivalist Jonathan Edwards.

Alamy

AlamyKeller lauded Edwards as theologically orthodox, pious, and culturally engaged. The problem, as Keller saw it, was that when Edwards died, evangelicals couldn’t hold together these three traits. While they flowed separately in different ministries, Keller bemoaned that they didn’t always join together in one mighty spiritual river. He believed that if Christians could unite these three streams once more, we would see an end to the spiritual drought of the post-Christendom West.

He never quite saw that happen. Indeed, the populist-elite division stems the spiritual tide. But two years after his death, we find that Keller has left us enough clues that could, if the Lord wills, guide the church into faithful and effective mission for the 21st century.

J. T. Reeves was a senior at Wheaton College in 2023 when he and his friends drove down to Wilmore, Kentucky, to join the Asbury Awakening, along with an estimated 50,000 people who flooded the university campus over 16 days of prayer and worship.

Asbury’s events resonated with Keller’s description of the central role of prayer in past awakenings. As he wrote in his paper “The Decline and Renewal of the American Church” (first published in its entirety in 2022):

There is always corporate prayer—extraordinary, kingdom-centered, prevailing prayer. Prayer not merely for our individual needs but for the power and gospel of God to be manifest (Acts 4:24–31). This is prayer beyond the normal daily devotions and worship services and, as much as possible, should be united prayer, bringing together people who do not usually pray together.

The Asbury outpouring was a model collaboration between institutional leaders who resisted outside influences and students who followed the unpredictable leading of the Holy Spirit. Reeves wrote how the revival jolted him into a deeper prayer life and how God awakened him from a spiritual haze accelerated by “the current of our screaming algorithms.” Corporate prayer seems less plausible when we’re scrolling ourselves to death.

Compared to older generations, you’re less likely to hear younger adults today describe their “quiet time” and more likely to learn about their “rule of life” or “daily liturgy.” Edwards would understand—as a teenager, he adopted 70 resolutions for his life. To follow suit today, we need habits that keep us from reaching for the smartphone every spare moment. Hearing from God often requires taking out the earbuds.

“Spiritual renewal brings an extraordinary sense of God’s presence, of increased communion with God (1 John 1:3), of ‘joy unspeakable and full of glory’ (1 Peter 1:8),” Keller wrote in 2022. Only God knows if we’ll see unspeakable joy wash over the country in our lifetimes. If we do, it probably means younger adults are practicing the “liturgy of the ordinary,” as Tish Harrison Warren put it, seeking and sensing God’s presence in all of life.

Keller modeled this life of prayer, this evangelical thirst to taste and feel the love and presence of God. In the tumultuous days of the COVID-19 pandemic and George Floyd protests, criticism of Keller increased, especially from populist corners of the Reformed community. Institutions creaked and cracked under pressure. Many leaders lost their bearings and moorings. Longtime friendships fractured under the pressure of social media spats.

As he fought for his life after his 2020 diagnosis of terminal pancreatic cancer, Keller grew more patient, joyful, hopeful, and forgiving, even though he was blamed for much that had little or nothing to do with him. The power of his prayer life was evident.

When he died, tributes poured in from across the Christian community. Cardinal Timothy Dolan offered St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York for the memorial service. Few Christian leaders could boast a better ministry résumé than Keller’s. But in eulogies published across mainstream publications, I didn’t see much discussion of his accomplishments. Instead, I saw repeated homages to his pious character, in private as in public.

Whether populist or elite, skeptical or institutional, younger Christian leaders should aspire to his example as he followed Christ in prayer. Spiritual outpourings such as the Asbury Awakening come neither from central planning nor from social media condemnations but by patient and persistent prayer from God’s people.

Even though Keller counted friends among institutional elites, he shared many populist critiques of Western cultural decay. As Christianity declined, he observed that the Enlightenment had failed to deliver cultural solidarity and meaning. Families, neighborhoods, and institutions—such as the academy—have faltered without a unifying vision provided by Christianity. This resulted in “greater isolation, loneliness, anomie, anxiety, and depression,” Keller wrote in 2022. He continued,

As the percentage of the population going to church declined, and as the radical individualism of the West became more pervasive, the original Enlightenment vision of a society based on secular human reason alone came largely to pass. But it has not led to unity at all. Western society in general and U.S. society in particular are polarized, fragmented, and ungovernable as everyone adopts their own meaning in life and moral values.

One example of renewal comes from the life of Molly Worthen (who wrote a tribute after Keller’s death for The Atlantic). Worthen had reached the pinnacle of her academic field with a PhD from Yale University and articles in The New York Times. She taught history at the highly ranked University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She looked forward to a long career as a respected public intellectual.

But she wasn’t fulfilled. She entered the academy looking for truth, yet it seemed that the purpose of the academy had evolved into something less certain and clear—more political posturing than searching for knowledge. In an interview with Southern Baptist pastor J. D. Greear, she mentioned how she sometimes wanted to believe as evangelicals do. Greear could hardly ask for a better prompt. Knowing her academic inclination, he put her in touch with Keller.

At Keller’s recommendation, Worthen read N. T. Wright’s The Resurrection of the Son of God, which challenged her with overwhelming evidence for the bodily resurrection of Jesus. C. S. Lewis’s Space Trilogy opened her imagination. Combined with Greear’s urgent appeals, these resources eventually led Worthen to confess faith in Christ, wading into the waters of baptism at Greear’s Southern Baptist megachurch wearing a “Jesus in my place” T-shirt.

Worthen is hardly alone in turning to Christianity amid dissatisfaction with modern life, which feels increasingly unlivable to many. Sarah Irving-Stonebraker, another professional historian, tells the story of her adult conversion in Priests of History. When Keller published The Reason for God, New Atheists such as Ayaan Hirsi Ali were riding a wave of cultural skepticism toward organized religion, from evangelical Christianity to radical Islam. Yet by 2023, Hirsi Ali had become a Christian too.

“The only credible answer [to the decline of the West] . . . lies in our desire to uphold the legacy of the Judeo-Christian tradition,” she wrote of her conversion. At first, some wondered whether Hirsi Ali had only fallen in love with the Western culture that delivered her from abusive expressions of Islam. Subsequent interviews indicated deeper spiritual transformation that caught the attention of Richard Dawkins, who has taken to calling himself a “cultural Christian.”

High-profile conversions reveal one path toward influencing and ultimately changing culture-shaping institutions. Revival could come again from the top down, as it did under Jonathan Edwards’s grandson Timothy Dwight, who was the president of Yale University during the Second Great Awakening. But Hirsi Ali’s conversion suggests a possible revival from the bottom up as populist dissatisfaction spreads across the West, especially with elite institutions enforcing divisive identity politics around sexuality.

Though Keller was more identified with the elite strategy than the populist alternative, he personally experienced revival on the margins. Keller and his InterVarsity Christian Fellowship friends at Bucknell University could hardly count on support from the administration or professors as their chapter grew overnight during the Jesus Movement of the 1970s. And no one I know was predicting revival on the Upper East Side of Manhattan in the 1980s after nearly a century of steady church decline.

Toward the end of his life, Keller anticipated widespread dissatisfaction with the Enlightenment and its aftermath. Like the populists, he saw an opening for the gospel as the sexual revolution turned bitter.

At least since the 1960s, a historical, orthodox sexual ethic has hampered the appeal of Christianity in the West. Between 2012 and 2016 in particular, popular perception of Christian views on sexuality shifted from embarrassment to harassment, especially among cultural elites. Once dismissed as prudes, Christians became ostracized as bigots in the culmination of a long-building shift in how individual identity develops across the West.

“The triumph of the modern self and of the sexual revolution for the loss of Christianity’s credibility can’t be over-estimated,” Keller wrote in 2022.

The Christian sex ethic is seen now as unrealistic and perverse. This is massively discrediting and makes biblical faith implausible to hundreds of millions both inside and outside the church. . . . The idea that you simply discover and express yourself is an illusion. Nevertheless, this view has swept society and is seen as common sense.

But when I talked to Keller just a month before he died, he could see the outlines of a shift in popular circles. Witness secular feminist Louise Perry with her 2022 Case Against the Sexual Revolution. Or Christine Emba’s Rethinking Sex from the same year. J. K. Rowling’s relentless feminist critique of transgender ideology combines the elite influence of an enormously wealthy author with populist disregard for institutional pressures. And President Donald Trump’s successful 2024 campaign channeled populist anger toward institutions—media, schools, entertainment, and hospitals—that have foisted unpopular transgender policies on the public.

The sexual revolution has led to a sexual recession, Nancy Pearcey observes in her 2023 book The Toxic War on Masculinity. By pushing the sexes away from each other and then turning them against each other, the sexual revolution has failed to deliver on its promises of progress.

Far from needing to update our theology, we can hold to orthodoxy to keep from being swept into the dustbin of history with cultural fads. It may not always be in season with popular culture, but God’s law is always good. If you want to write tomorrow’s headlines, stick with the old, old story—the gospel wins out in the end.

As much as any other Christian of his generation, Keller engaged with the hardest arguments against Christianity. He defended the gospel and proclaimed Christ in some of the most hostile settings of the elite West.

Keller approached these exchanges with the biblical assumption that his opponents were made in the image of God. Before he identified where Christians and non-Christians disagreed, he tried to affirm something good and right in a religious skeptic’s outlook on the world.

He approached people with curiosity, not speaking contemptuously or dismissively. He acknowledged some critiques of the church as valid. And he didn’t pretend that Christians have everything figured out. His apologetics assumed that, in a secular age, Christians have many of the same questions or doubts as non-Christians.

Yet anyone who has listened to his sermons knows Keller didn’t coddle his left-leaning Manhattan neighbors. He challenged them—directly, forcefully. He exposed them as believers—in something or someone that would inevitably fail them. And he invited them, with passion and pleading, to trust in Christ alone for the forgiveness of their sins and the life everlasting.

It may surprise some to learn what Keller prioritized for the church in an increasingly secular society. “Christian education, in general, needs to be massively redone,” he stated in “The Decline and Renewal of the American Church.”

We must not merely explain Christian doctrine to children, youth, and adults, but use Christian doctrine to subvert the baseline cultural narratives to which believers are exposed in powerful ways every day. We should distribute this material widely to all, flooding society, as it were, with it.

Like many populists, Keller saw the need to prioritize Christian education for spiritual formation. He saw the temptation for those inside the church to lose their way, especially when they’ve been inundated with the values of elite institutions.

The thing about exposing secular cultural narratives around identity and progress—to take just two examples—is that Christians aren’t immune to them. It’s not as if only non-Christians think that happiness can be found in accumulating goods and experiences, or that a political party can help them feel secure in the world. And the pursuit of institutional power drives populists as much as elites. Regardless of our religious or political beliefs, we’re all shaped by similar goals and desires. The real questions are: For what? For whom? And how?

To use institutional and cultural power for good, Keller believed, Christians need counter-catechesis. For instance, the world says power should be wielded to enact vengeance. In contrast, how can Christians exercise power in ways that don’t turn victims into victimizers or compound injustice with injustice? How can we love our enemies in obedience to Jesus?

Keller didn’t exactly recommend removing ourselves from the secular world. But he did believe that Christians need “moral ecologies”—especially churches—to help us live what we profess.

To this end, he labored through Redeemer City to City to help start more than 2,000 churches since 2001. He commended vocational groups that shape Christians working in specific professions and valued the role of singles in churches. Like many evangelicals before him, Keller saw deep power in small groups united in prayer, confession, Bible study, and practical support.

These moral ecologies have become more important in the past two decades, when the internet has made it far easier to live according to the cultural narratives of the world than according to the Scriptures. Social media can create moral ecologies too—but often negative ones that form around what a group opposes. Such communities fail to produce the fruit of the Spirit. They don’t help disciples of Jesus pursue the good, including love for the outgroup.

It’s hard to imagine widespread spiritual revival that doesn’t bear the fruit of the Spirit. What would the world find compelling in a church that mirrors society’s own sins?

Instead, non-Christians will find refreshment in a church that puts down the smartphones to pray together. Choking on the dust of loneliness kicked up by the sexual revolution, they’ll discover true belonging among Christians who have counted the cost and followed Jesus. Betrayed by the Enlightenment, they’ll follow the river of life to the light that will never be extinguished (Rev. 22:1, 5).

With history as our guide, revival in the 21st century will be a spiritual torrent fed by three streams—personal piety, biblical orthodoxy, and cultural engagement. These streams will bring spiritual refreshment to lands parched by the failed modern pursuit of individual identity apart from Christianity.

The time is right for evangelical elites and populists to collaborate once more. We agree on many of the problems. We agree on many of the solutions. And we can unite as Christians around an apologetic method grounded in biblical theology and adorned with spiritual fruit.

Christians, whether elite or populist, shouldn’t feel comfortable in this world. We should feel restless for our forever home with God in the new heavens and the new earth. Maybe revival won’t come in our lifetimes. But every revival starts with Christians desperate to catch a glimpse of that future on this side of eternity.

Tim Keller didn’t see that national revival during his ministry. But he prayed that we would.

Collin Hansen is vice president for content and editor in chief of The Gospel Coalition, executive director of The Keller Center for Cultural Apologetics, host of the Gospelbound podcast, and the author of Timothy Keller: His Spiritual and Intellectual Formation.