Historian John Dickson knows that “early” Christian music usually refers to sacred chants from the ninth or tenth century. So when he noticed a reference to an ancient hymn from hundreds of years before that—way back in the third century—he was immediately curious.

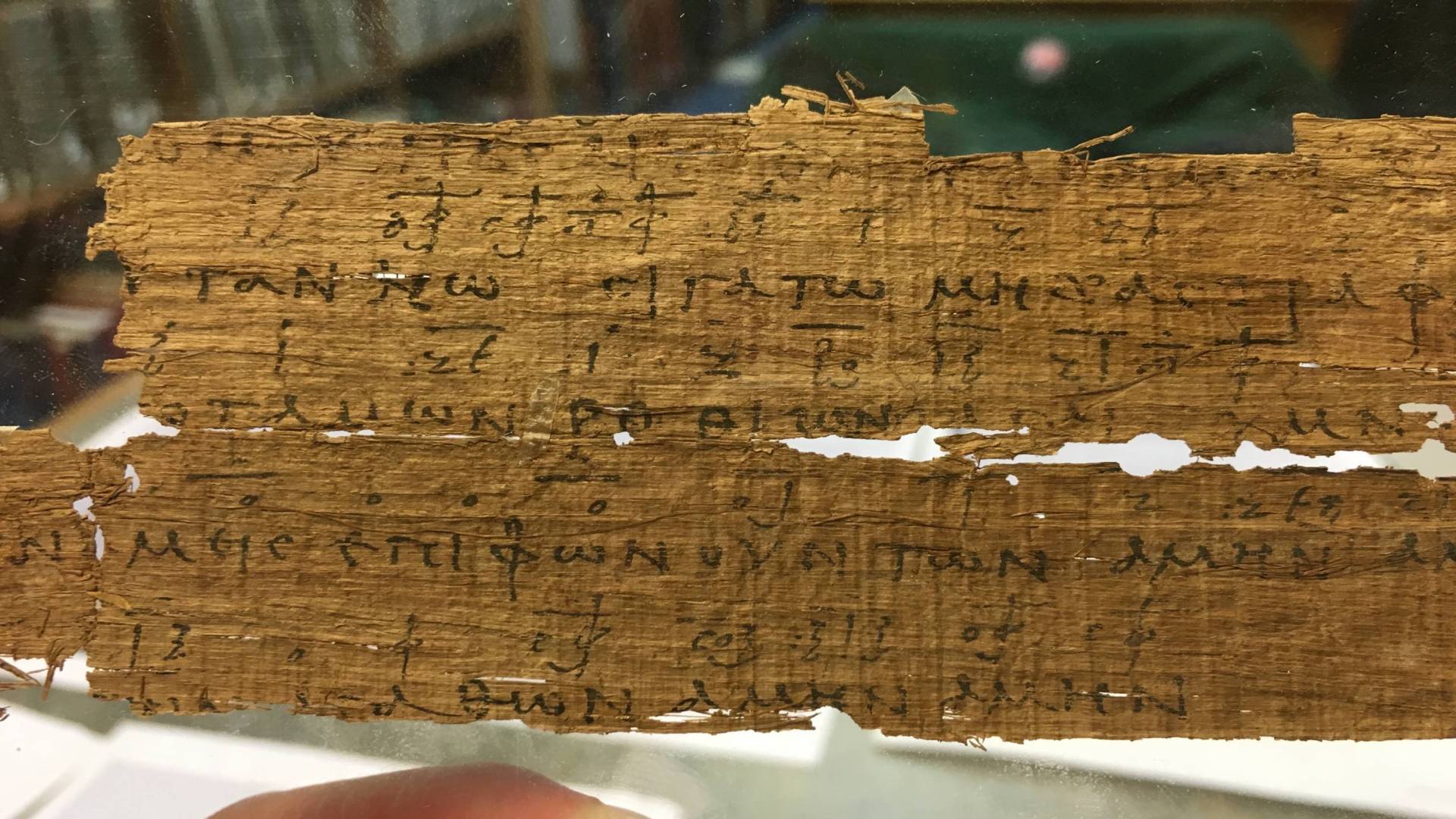

The words and musical notations to this obscure sacred song, penned in Greek on a tattered papyrus fragment uncovered over a century ago, named the “Father, Son, and Holy Spirit” and responded to pagan beliefs.

“The Christians who produced this were trying to create music that was understandable for their surrounding culture,” Dickson told CT. “It’s simultaneously worship and public Christianity.”

The ancient Greek hymn is by far the oldest surviving piece of Christian music—it predates the next notated work by six centuries. Inspired by the ancient fragment, Dickson reached out to Ben Fielding, a fellow Aussie and a songwriter for Hillsong, to turn it into a singable work for today’s church.

Early conversations between Dickson and Fielding eventually led to a collaboration with Grammy-winning worship artist Chris Tomlin, culminating in the production of a new worship song, “The First Hymn,” and a documentary about the discovery and study of the papyrus fragment containing the hymn.

Courtesy of The First Hymn movie

Courtesy of The First Hymn movieThrough the Psalms and other biblical texts, Christians have had access to words that might have been sung by ancient worshipers. But this early hymn is the first example of Christian music with both text and musical notation preserved—offering rare hints about how the music of early Christian gatherings might have sounded.

“The First Hymn” pulls from the Trinitarian themes and reverence for creation in the ancient song, showcasing Tomlin’s knack for writing simple, syllabic melodies that hold up with minimal accompaniment or full band. It feels thoroughly contemporary even though the text and melody are based on a piece of music likely sung by third-century Christians.

Christians across denominations have been captivated by the idea of singing songs with deep roots in the historic church. Over the past two decades, some evangelicals in the US have migrated to Orthodox or Anglican churches in search of historically rooted faith practices. The Catholic church is experiencing a resurgence of enthusiasm for tradition. Interest in hymns and hymnals is on the rise in a variety of church settings.

“The First Hymn,” like the preceding “ancient-future” worship trend of the 2000s, offers connection to early believers by adapting or reviving an artifact of the faith for modern Christians.

“I’m skeptical of fads, including the fad of ‘going back,’” said Dickson. “I don’t think of this as ‘going back.’ It’s giving something back to the church.”

Now a faculty member at Wheaton College, Dickson has been a lecturer in Hebrew, biblical studies, and classics at institutions in Australia, the UK, and the US. But in the ’90s, he was a singer-songwriter in a rock band. He’s long had an interest in putting ancient words to music, and the text of what scholars call “the Oxyrhynchus hymn” (or P.Oxy. XV 1786) presented the opportunity to join in what Dickson sees as a work of public theology by early Christians.

The Oxyrhynchus hymn was found in a massive collection of papyri uncovered in Egypt. The Oxyrhynchus Papyri contain an estimated half-million fragments, mostly records and correspondence.

The fragment on which the hymn was written preserves 35 words and the accompanying melody and rhythm in ancient Greek musical notation. It is believed to be the conclusion of a longer song.

Let all be silent:

The shining stars not sound forth,

All rushing rivers stilled,

As we sing our hymn

To the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit,

As all Powers cry out in answer,

“Amen, amen.”

Might, praise, and glory forever to our God.

The only giver of all good gifts.

Amen. Amen.

“‘Giver of good gifts’ was one of Zeus’s epithets,” said Dickson. “But the writer says ‘only giver of all good gifts.’ This may be a nod to Zeus.”

Dickson suggested that the writer of the hymn may have been directly answering or conversing with the competing religious beliefs of the time, something Paul modeled in his letters.

“The phrase ‘in him we live and move and have our being’ comes from a hymn to Zeus,” Dickson observed. “Paul can quote it [in Acts 17:28] and say that this finds its fulfillment in the one true God.”

The theme of cosmic silence (“Let all be silent”) would have resonated with non-Christians in ancient Greece and Egypt, said Dickson.

Musica mundana—the music of the spheres—was a philosophical concept articulated by ancient Greeks to describe the harmony and balance of the heavenly bodies, governed by mathematical relationships. The call to silence of the heavenly bodies was something the Greeks would recognize as a command that only a powerful god could give.

“The thematic setting of silence is pagan,” said Dickson, noting that biblical texts like Psalm 148 most often call the natural world to join in a chorus of praise. “Asking all creation to be silent instead of joining in praise is weird from a biblical point of view.”

Courtesy of The First Hymn movie

Courtesy of The First Hymn movieWhile “The First Hymn” is the first effort to introduce the ancient song to a general audience, musicologists and historians have been studying it since 1922. Charles Cosgrove’s 2011 book, An Ancient Christian Hymn with Musical Notation: Papyrus Oxyrhynchus 1789: Text and Commentary, provides extensive analysis and history of the fragment.

Cosgrove observed that the hymn is a challenge for researchers because it isn’t of central importance for scholars of ancient Greek music and because historians of Christian liturgy generally lack the specialized knowledge necessary to fully grasp and analyze the Greek musical notation.

In academia, the hymn has remained in no man’s land. Its relative isolation and obscurity has to do with the fact that there are so few contemporaneous artifacts to compare it to.

“One hopes that in further discoveries … another such hymn will come to light,” wrote Cosgrove. “But for now, P.Oxy. 1786 is our only example of pre-Gregorian Christian music. For that reason alone it deserves a comprehensive treatment.”

The adaptation of P.Oxy. 1786 by Dickson, Fielding, and Tomlin is perhaps their version of a comprehensive treatment: an accessible song and a documentary about its history for those hungry for a connection to the historic church.

The documentary premiered at Biola University on April 14, followed by a live premiere of the song at the Museum of the Bible in Washington, DC, on April 15.

Resources for churches interested in using the song for congregational worship are already available on platforms like MultiTracks, where worship leaders can download charts and a collection of performance tracks—including all six electric guitar parts and a background choir.

“The First Hymn” is a stirring anthem in the recognizable style of today’s popular worship music, featuring layers of synth textures and a clear verse-chorus structure that builds in intensity from a relatively sparse first verse.

Other than the title, there’s nothing in the text or production that hints at the song’s ancient origin, as the modern setting avoids the potentially gimmicky inclusion of tropes to signal the old or exotic (such as the use of harmonic minor scales or the sound of a zither). Tomlin and Fielding have reworked the lyrics so they fit neatly over a singable melody.

Tomlin calls the song “a sacred gift passed down from the early Church,” connecting its story to the lives of martyrs and persecuted Christians throughout history. “Now, 1,800 years later, we stand in a long line of brave and bold believers, singing alongside them.”

Dickson said that today’s church can learn from the openness of early Christians and their ability to “use pagan motifs to convey Christian doctrine,” even complicated doctrines like that of the Trinity.

“The cool thing is, there’s nothing new here,” Dickson said. “The Trinity is the center; it’s the nature of God in three persons. And here’s the oldest hymn we have, reminding us of that.”