Every April since 1963, thousands recall Martin Luther King Jr.’s Letter from Birmingham Jail and its timeless call to reject complacency in the face of injustice. Aimed not at staunch segregationists but at well-meaning white moderates, King’s letter sent shock waves through the nation and countless churches. His words still challenge us today—but back then, they forced many to reckon with their own passivity in real time.

One of those people was R. B. Culbreth. As pastor of Metropolitan Baptist Church (today Capitol Hill Baptist Church) in Washington, DC, Culbreth pastored a congregation that, like many Southern Baptist churches, had not yet integrated its membership. For years, Metropolitan embodied the kind of moderation King decried: supporting civil rights in theory while hesitating to take a firm stand. But around the time King penned his letter, Culbreth shifted his views, which we know about because of a recently discovered letter written by Carl F. H. Henry, a Metropolitan member who was also the first editor of Christianity Today.

On May 2, 1963, Culbreth would have watched in horror, alongside millions of Americans, as television channels broadcast brutal scenes from civil rights protests against racial segregation in Birmingham, Alabama. Day after day, newspapers printed vivid pictures and television networks aired shocking footage of peaceful demonstrators being knocked off their feet by high-pressure hoses and attacked by police dogs. For Culbreth, the images would have been more than just headlines—Birmingham was his hometown, a city he loved.

Just weeks before those images hit the news, King wrote directly to people like Culbreth. As clergy far and wide were digesting the letter and the violence in Birmingham, something happened that changed Culbreth from a typical white moderate to someone who publicly supported integration.

By 1963, Metropolitan Baptist Church was nearly a decade into grappling with how to navigate the changing racial and political landscape as a downtown church in the nation’s capital. In the early 1950s, Black Washingtonians endured a city nearly as rigidly segregated as any in the Deep South. The only privilege they had over their counterparts in Atlanta or Birmingham was the ability to ride in the front of a bus—until it crossed into Virginia.

Many African Americans lived in Washington’s notorious “alleys”—cramped, squalid areas hidden behind main thoroughfares. These dwellings, originally built as horse stables, lacked plumbing and basic sanitation. Some 15,000 were forced out of their homes during the redevelopment of southwest Washington in the 1950s, relocating to the area of southeast Washington known as Anacostia. To this day, many of the city’s low-income and predominantly Black communities remain concentrated in Anacostia, a lasting legacy of mid-century displacement and segregationist housing policies.

Following the Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 striking down segregated public schooling, resistance to integration intensified, leading to an explosion of private Christian schools. In 1953, Metropolitan considered starting its own Christian day school modeled after a church school in Charleston, South Carolina, citing concerns about evolution and racial integration. But after heated debate, the board of deacons narrowly voted against it.

By that time, Metropolitan had begun sponsoring a Sunday school and chapel in Anacostia, the fruit of the labors of an elderly widow and longtime white member named Anna Johenning. However, the once-majority-white neighborhood around the chapel, like much of the city, was undergoing demographic changes, and Metropolitan’s leadership, fully aware of the sensitivities of “racially mixed areas,” adhered to the Southern Baptist policy of segregated services. African Americans were welcomed to weekday programs but were encouraged to attend a separate afternoon service on Sundays.

As the conscience of the nation came under growing pressure to desegregate, members began questioning the chapel’s practice of segregated services. In response, Culbreth explained the church’s position in a 1962 letter to Samuel Southard, a professor at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary. He noted that while Metropolitan had no Black members, African Americans who visited Sunday services were seated without discrimination. The Southeast Chapel followed a similar approach in its morning worship service, while Black attendees were encouraged to attend an afternoon service designated for them. Weekday programs for children were fully integrated, with roughly 60 percent white and 40 percent Black participation.

It’s unclear why the chapel’s children’s programs were integrated while Sunday services were kept separate. Culbreth insisted that the church was neither seeking integration nor actively maintaining segregation, and he acknowledged that many members would oppose any formal integration efforts: “We are not seeking to integrate, neither are we making an issue of it to remain a segregated church as such,” he wrote in his letter to Southard. Then came Birmingham.

The brutal images of police dogs and fire hoses turned on peaceful demonstrators shocked the nation. But what I believe moved Culbreth even more was King’s open letter, which was addressed to white pastors and civic leaders sympathetic to the cause of justice yet cautious about its methods.

“I have almost reached the regrettable conclusion that the Negro’s great stumbling block in his stride toward freedom is not the White Citizen’s Counciler or the Ku Klux Klanner, but the white moderate, who is more devoted to ‘order’ than to justice,” King wrote on April 16, 1963. He rebuked those who called on African Americans to “wait” for relief while shielded from the suffering that flowed out of “the disease of segregation,” noting further that “shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will.”

A few weeks later, Culbreth delivered a sermon titled “The Musts of Jesus.” In it, he decisively broke with his previous moderation, publicly coming out in favor of integration and condemning the silence of white ministers in Birmingham, the position he had previously defended. It’s unclear whether Culbreth viewed the shift as repentance. The change, though, was big enough for others to notice.

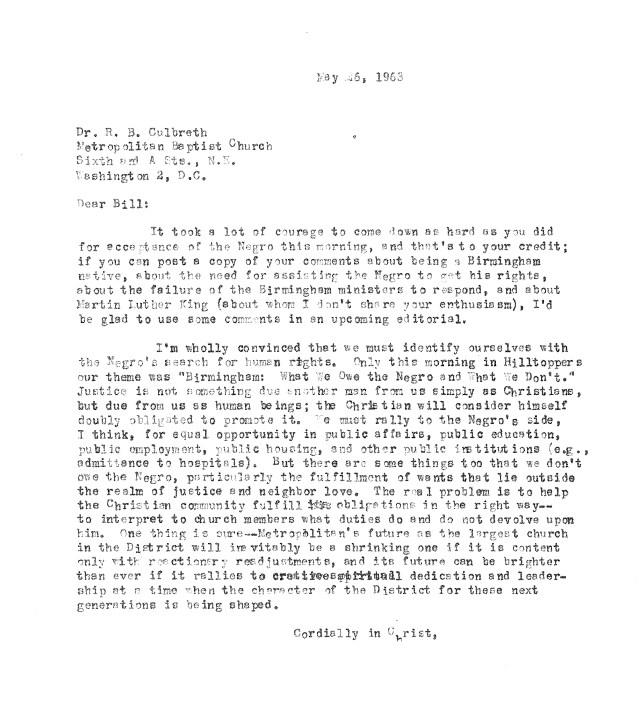

After the Sunday sermon, Henry, CT’s top editor at the time, told Culbreth in a letter that his call “for acceptance of the Negro” had taken “a lot of courage.”

“And that’s to your credit,” Henry added, while also expressing some concern regarding King (“about whom I don’t share your enthusiasm,” he wrote, without offering further details). Among other things, Henry commended Culbreth for his words about “the failure of the Birmingham ministers to respond” to civil rights demonstrations.

“I’m wholly convinced that we must identify ourselves with the Negro’s search for human rights,” continued Henry. “Justice is not something due another man from us simply as Christians, but due from us as human beings; the Christian will consider himself doubly obligated to promote it. We must rally to the Negro’s side, I think, for equal opportunity in public affairs, public education, public employment, public housing, and other public institutions.”

CHBC Archives

CHBC ArchivesWhat Metropolitan needed, concluded Henry, was “creative spiritual dedication” at a time when the character of Washington (and of the nation) was being determined. Was the church ready for the challenge? Was it ready to repent from the sin of partiality and the comfort provided by silence?

After Culbreth’s sermon, members began showing a change of heart and moved toward desegregating services at the chapel in Anacostia.

The church’s deacons soon affirmed that “all candidates for membership shall be treated in the same manner,” rejecting any two-tiered approach to membership. By 1964, segregated services at the chapel were a relic of a not-so-distant past. When the chapel was finally ready to constitute itself as an independent church in 1966, the majority-Black congregation adopted the name Anna Johenning Baptist Church as a tribute to the member of Metropolitan who had initiated the work.

Metropolitan, which changed its name to Capitol Hill Metropolitan Baptist Church in 1967 and then to Capitol Hill Baptist Church in 1995, welcomed its first African American member in 1969: Margaret Roy. The fight for racial integration, however, was not quite complete. Four white families left the church when Roy joined. But despite experiencing some serious unpleasantness, Roy resolved “that she would treat people right regardless of how they may treat her,” she recalled in an interview conducted in 1997. At a women’s Bible study, Roy said one woman “turned her back on her,” but the same woman later “became a friend.”

Today, Anna Johenning Baptist Church—now called The Temple of Praise—and Capitol Hill Baptist Church, where I pastor, continue to preach the gospel in their respective communities on separate sides of the Anacostia River. They don’t maintain special ties. But a shared history unites them into one story, and a shared Spirit unites them into one body. And though a river divides them today, one day a river will unite them.

In Revelation, the apostle John paints a picture of the saints gathered around the river of the water of life, a crystal-clear body of water flowing from the throne of God. On either side of the river are the branches of the tree of life, whose leaves are “for the healing of the nations” (22:2). One day all the saints will join at the foot of that river to worship the Lamb. On that day (v. 4), every wound of sin and strife and every tear of injustice will be wiped away because we will see his face.

Caleb Morell is an assistant pastor at Capitol Hill Baptist Church and the author of A Light on the Hill: The Surprising Story of How a Local Church in the Nation’s Capital Influenced Evangelicalism.