This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here.

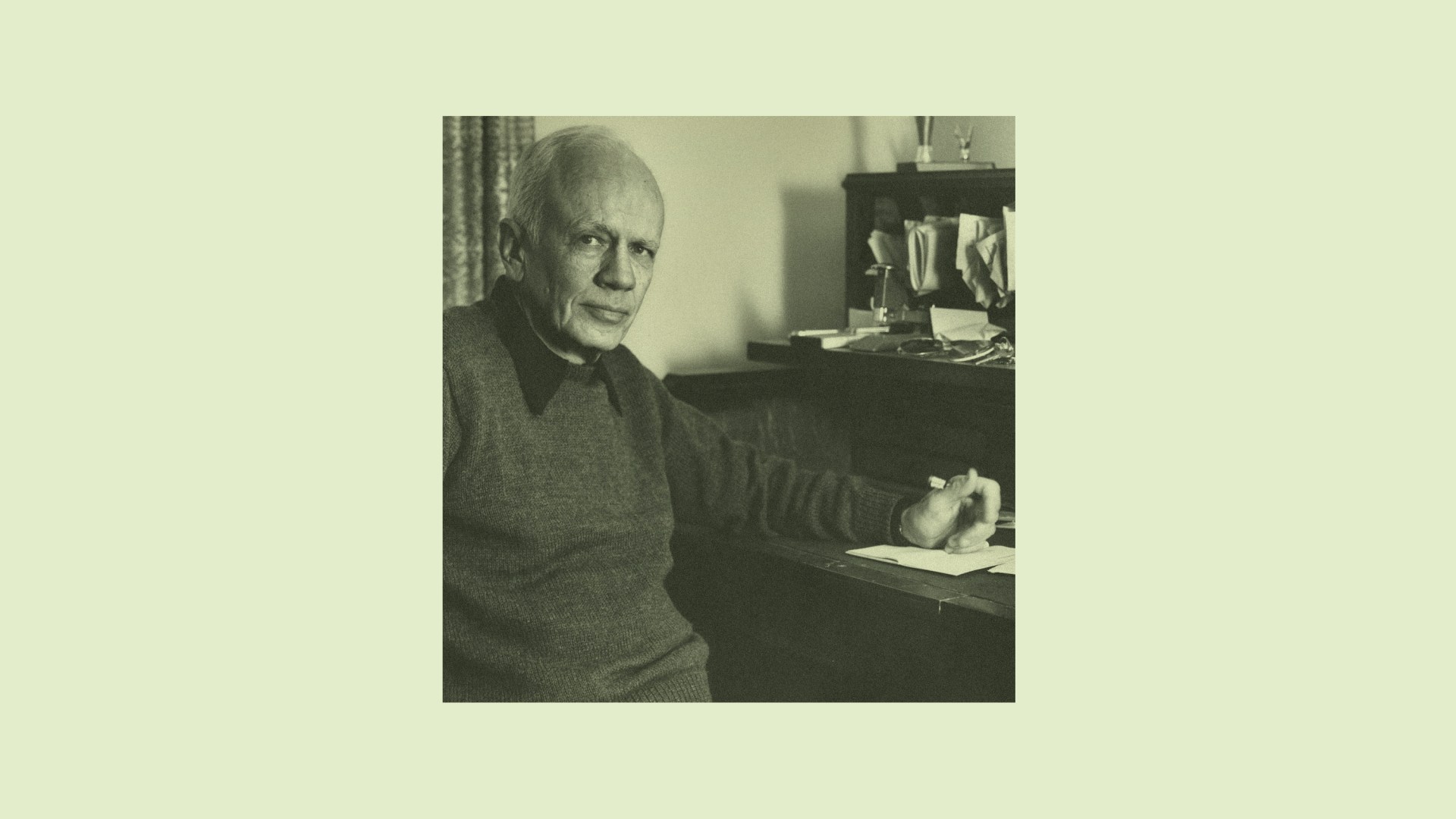

If you’ve ever looked around at the chaos of the current moment and wondered, “Who could have seen this coming?” I have an answer: Walker Percy.

Percy, an American writer, died 35 years ago this week—long before Trump, Twitter, TikTok, or transgender sports debates. But more than half a century ago, he eerily foresaw something like 2025, in which technology, tribalism, and spiritual emptiness converge. If we’re to find our way through the madness, maybe we should listen to what he had to say.

“A serious novel about the destruction of the United States and the end of the world should perform the function of prophecy in reverse,” Percy wrote of his 1971 novel, Love in the Ruins: The Adventures of a Bad Catholic at a Time Near the End of the World. “The novelist writes about the coming end in order to warn about present ills and so avert the end.”

Love in the Ruins is a kind of Narnia, except the children walk through the wardrobe into a post-Christian West with no Aslan in sight. The central threat isn’t nuclear fallout or alien invasion but a nation fractured along the lines we now call red and blue America.

In this “time near the end of the world,” the country is split into a right (self-identified as “Knotheads”), driven by resentment toward minorities and rage at elites, and a left fueled by ideologies of sexual liberation and secularism. Religion becomes politics; politics becomes religion.

The protagonist is Tom More (yes, named after that Thomas More), a psychiatrist, sex-addicted alcoholic, and lapsed Catholic living in a Louisiana suburb after the spiritual and political collapse of America.

More observes that there are left states and right states, left towns and right towns, even left movies and right movies. The center is gone. The younger generation, he says, are would-be totalitarians: “They want either total dogmatic freedom or total dogmatic unfreedom, and the one thing that makes them unhappy is something in between.”

Families are fractured by politics, churches by ideology. More’s Catholic church splinters into three: a booming “American Catholic Church” in Cicero, Illinois, defined by right-wing politics and celebrating “Property Rights Sunday”; a “death-of-God” progressive church, where priests monitor sexual response in scientific labs; and a tiny, irrelevant remnant still loyal to Rome—now politically unintelligible in a world ruled by ideology.

Two characters survey the news:

“There are riots in New Orleans, and riots over here. The students are fighting the National Guard, the Lefts are fighting the Knotheads, the blacks are fighting the whites. The Jews are being persecuted.”

“What are the Christians doing?”

“Nothing.”

The collapse in Love in the Ruins is not just political or cultural—it’s personal. The world is falling apart because people are falling apart. The underlying issue is a civilization that no longer knows what a human being is for. That’s a question politics cannot answer, yet politics has become a surrogate religion for people without a deeper anchor.

Percy’s vision is strikingly familiar: a society beset by mental illness that seems tailored to political tribe.

“Conservatives have begun to fall victim to unseasonable rages, delusions of conspiracies, high blood pressure, and large-bowel complaints,” More observes. “Liberals are more apt to contract sexual impotence, morning terror, and a feeling of abstraction of the self from itself.”

More invents an “ontological lapsometer,” a device meant to diagnose and correct psychological imbalances—massaging rage out of right-wingers’ brains and anxiety out of left-wingers’. It’s treated as a technological fix for what ails us. But More knows better.

The deeper problem is that people now see themselves either as angels—disembodied, limitless, with pure will—or as beasts driven by appetites and enemies. We see it now too. Tech billionaires promise artificial intelligence chatbots to supply friendships we no longer cultivate, authoritarian ideologies rise again, and many political and religious leaders defend or ignore it. The center does not hold.

Percy recognized that religion often seems helpless in such moments. He imagined scientists walking home from the lab on a Sunday morning, passing a church where the door is ajar and a preacher says, “Come, follow me.”

How do the scientists respond? Percy suggested they wouldn’t reject the invitation—because they’re not in the kind of predicament that allows them to even hear it.

“The question is not whether the Good News is no longer relevant,” Percy wrote, “but whether it is possible that man is presently undergoing a tempestuous restructuring of his consciousness which does not presently allow him to take account of the Good News.”

So what do we do? The answer is not utopian schemes or dystopian despair. It is, paradoxically, to move deeper into the crisis—until we can feel what’s missing. As Percy put it, the goal is to recover the self “as neither angel nor organism but as a wayfaring creature somewhere in between.”

That requires humility. We can’t fix the world or ourselves. The novel ends not with More’s invention saving the day but with its failure. What was meant to heal only deepens the wound.

And yet More finds a way forward—not through grand solutions but through the small, human steps of humility, connection, and grace. Even recognizing his lack of contrition becomes its own kind of mercy. He stops trying to save the world. He starts to live.

We can begin again only when we are willing to be asked—and to answer—the question “What are you seeking?” In this way, catastrophe becomes the precondition for hope.

Only when we realize we are not “organisms in an environment” to be perfected—or to perfect others—can we begin to feel our cosmic homelessness, which might just point us home. Only when we see that we are in the ruins can we begin to look there for love.

Maybe the world is falling apart. Maybe it always has been. But that doesn’t mean you have to fall apart with it.

Russell Moore is the editor in chief at Christianity Today and leads its Public Theology Project.