Hundreds will meet near Pittsburgh in June as part of a 120-year tradition deemed the longest-running annual missions conference in the US.

This year’s New Wilmington Mission Conference, held at a lakeside pavilion on the campus of Westminster College, will welcome as special guests some of the 54 mission workers who lost their jobs when Presbyterian World Mission shut down in March.

The end of Presbyterian World Mission—founded in 1837 as the Presbyterian Church (USA)’s foreign mission board—represents the latest consequence of declining giving and shifting stances around overseas evangelism in the mainline denomination.

PC(USA) blamed the decision on financial strain and Christianity’s global shifts away from the West to the Global South. Officials said some missionaries—the denomination calls them “mission coworkers”—were offered severance packages or new positions in the denomination. Some will serve as liaisons to immigrant communities, churches in the US, and mission networks abroad.

“As a denomination and as individuals, the future is unclear, and the callings are developing,” PC(USA) stated clerk Jihyun Oh said during an online chapel service in March honoring the legacy of Presbyterian World Mission. “Standing on the shoulders of the communion of saints that have embodied nearly 200 years of Presbyterian mission, we step forward in the knowledge that our desire to please God does please God.”

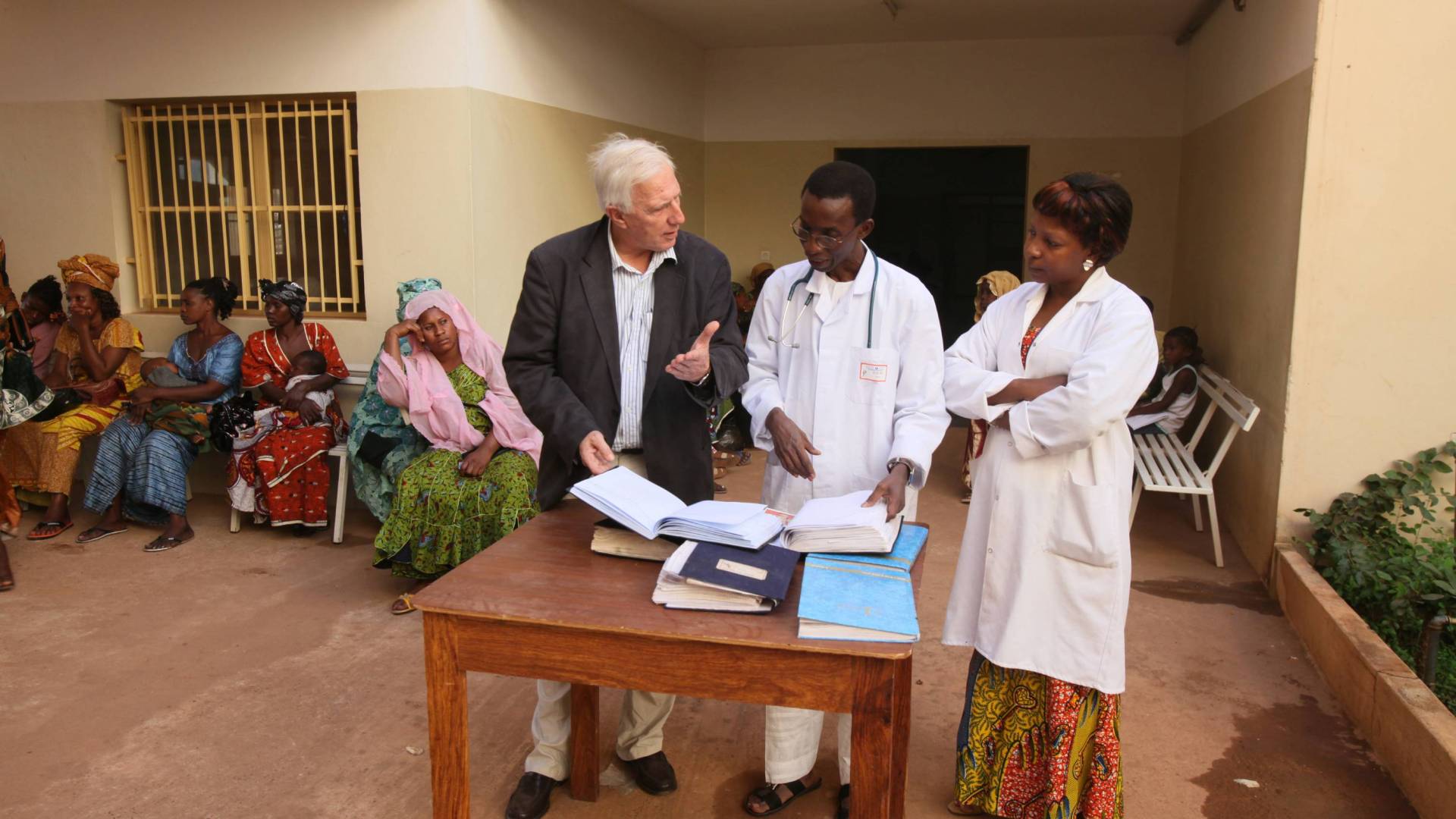

The closure comes at a time when faith-based organizations and ministries abroad are struggling to make up for funding deficits after the US State Department cut funding for programs like PEPFAR and USAID.

“Between the decline of mainline denominational missions and foreign aid gutting, there’s a much greater need for other churches to step up their giving,” wrote Matthew Loftus, a Christian doctor in Kenya, on X.

Loftus works at a hospital associated with the Presbyterian Church of East Africa, but it receives financial support from the PC(USA)’s Medical Benevolence Foundation, separate from Presbyterian World Mission.

The decision to close Presbyterian World Mission, in part, results from the “theological loss of nerve in the mainline,” according to David Dawson, a missiologist and retired PC(USA) executive presbyter for Shenango Presbytery in Western Pennsylvania.

The shift away from international missions dates back to the mid-20th century. Denominations like the PC(USA) and the Episcopal Church have grappled with missionaries’ associations with colonialism and with a broader “uncertainty in mainline settings for how to talk about evangelism and how evangelism relates to mission more broadly and social justice specifically,” said Scott Hagley, who teaches world mission and evangelism at Pittsburgh Theological Seminary.

As recently as 2010, Presbyterian World Mission supported 200 mission coworkers. In 2025, that number was down to 60, with 54 laid off in February.

By comparison, the Presbyterian Church in America’s foreign mission agency says it trains and serves 509 long-term missionaries. World Outreach, the foreign mission organization associated with the Evangelical Presbyterian Church, had 141 missionaries and co-op partners in 2021. Unlike the missionaries with Presbyterian World Mission, who were paid by the PC(USA), missionaries with these organizations raise their own funds.

With a few exceptions, such as the Southern Baptist Convention’s International Mission Board—which supports around 3,500 missionaries—denominational missions agencies are working on a smaller scale, with many missionaries raising their own funds and partnering with parachurch missions agencies instead.

Several mainline missions agencies have restructured or made cuts, wrote Jeff Walton with the Institute on Religion and Democracy.

According to Walton, the PC(USA)’s annual giving toward supporting missionaries peaked at $16 million in 2000 and fell to about $6 million by 2023. Denominational leaders say financial considerations were part of the decision to close but not the only factor.

The changes are the result of “two decades of listening to global partners across varied settings and context,” they wrote, and “the reality that more and more global partners are sending missionaries to the U.S. and have diaspora communities in our midst.”

Since the early 2000s, Dawson and fellow Presbyterians suspected the denomination would get out of international missions.

Frontier Fellowship and The Outreach Foundation, two other Presbyterian missions organizations, teamed up in 2006 to launch The Antioch Partners; the venture was meant to create another avenue for supporting Presbyterians on the mission field, Dawson said, “when it became clear the denomination was going to send fewer and fewer missionaries.”

Individual PC(USA) churches have also developed their own relationships with missionaries. In Washington, Bellevue Presbyterian (BelPres) Church belongs to a group of evangelical PC(USA) churches called The Fellowship Community and supports 9 missionaries and 15 ministries across the Americas, Africa, and Asia.

Richard Leatherberry, mission pastor at BelPres, said Presbyterian World Mission hadn’t “been a good fit for the focus areas we believe God has been calling our church to.”

Presbyterian World Mission staff have not always shared the PC(USA)’s progressive social stances. When the denomination approved same-sex marriage in 2014, Hunter Farrell, then-director of Presbyterian World Mission, said to “expect a significant decrease in the number of its global mission partners.”

In response to the March layoffs, some former mission coworkers signed an open letter to PC(USA) leadership expressing concern that theologically conservative missionaries would take up the work that Presbyterian World Mission had abandoned.

“When progressive Christians, communions, and mission-sending organizations leave a mission field, their absences are inevitably and invariably filled with voices, personnel, and mission partners who view Jesus and his ministry differently, in less inclusive and liberating ways,” the letter states. “Specifically, this impacts work with women and the ordination of women, with people in the queer community, and with communities on the margins.”

Some theologians see Presbyterian World Mission’s closure as the logical conclusion when a denomination embraces liberalism. More than 100 years ago, Presbyterian theologian J. Gresham Machen warned that liberal Presbyterians were using the same terminology as conservatives but with different meanings.

“History has proven Machen a prophet,” wrote Nathan Finn, professor of faith and culture and director of the Institute for Faith and Culture at North Greenville University. He notes that in 1983, the PC(USA) had over 3.1 million members. Today, membership is less than 1.1 million.

“Theological liberalism is incompatible with authentic Christianity. When churches or denominations begin to adjust to the spirit of the age, they inevitably deny the faith that was once and for all delivered to the saints (Jude 3).”

At the New Wilmington Mission Conference, missionaries will regroup and ask where Lord might be pointing them next. Dawson believes “healthy missiology recognizes that foreign mission is always done by congregations. Denominations help to foster it.”

Though the PC(USA) has “abdicated that responsibility,” Dawson said, the ministry will not stop. Presbyterians will find new ways to commit to it.