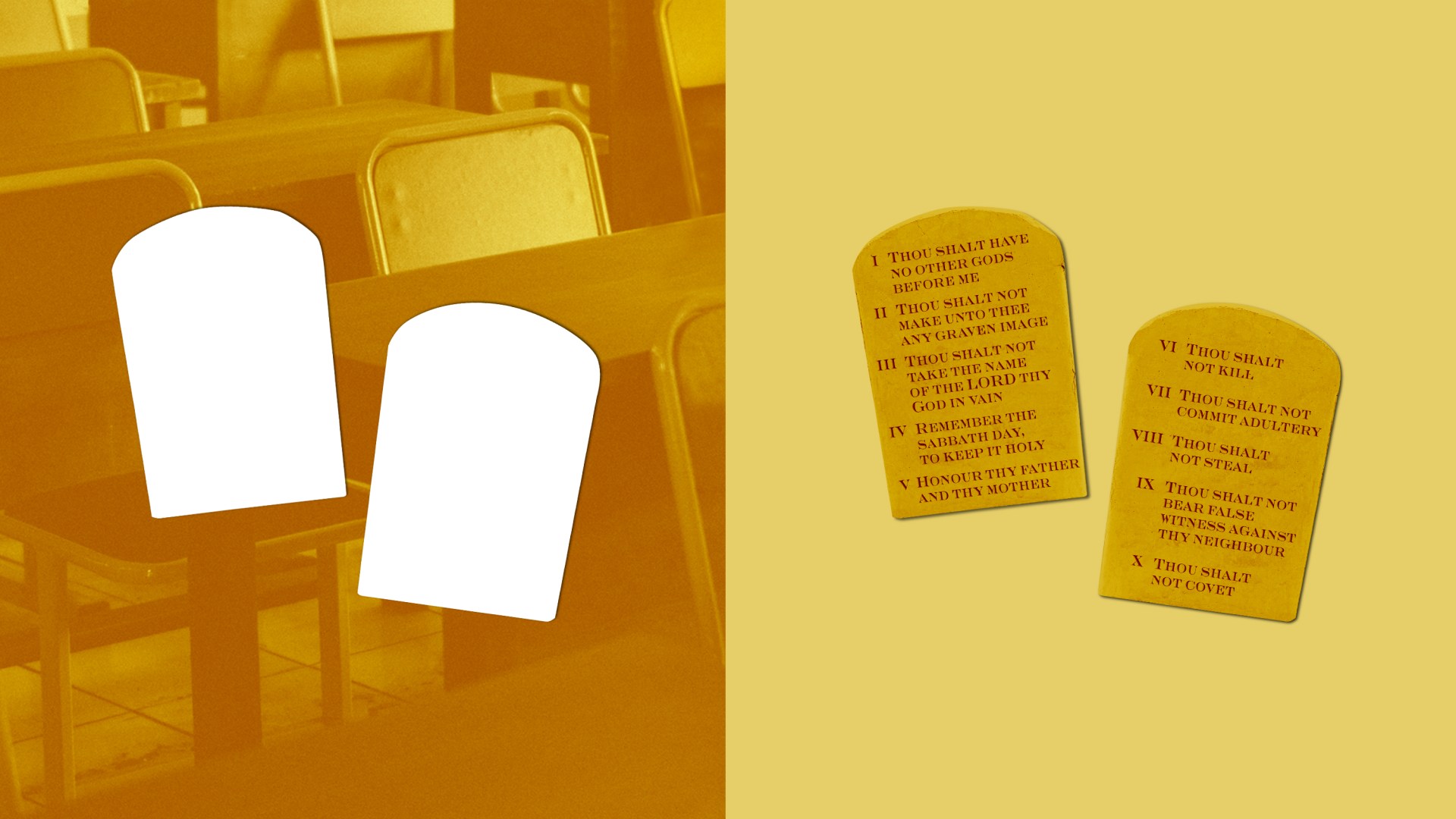

Efforts to post the Ten Commandments in public schools are not new, but the United States is seeing an uptick in support for these measures. Last year, Louisiana state legislature passed bill HB71, which requires the display of the Ten Commandments in a “large, easily readable font” in public classrooms from kindergarten to university.

Though the bill is currently experiencing legal challenges, that has not deterred Texas, South Carolina, Arkansas, and other states from attempting their own versions of legislation that require the Ten Commandments in public schools. Texas Senate Bill 10 passed in March and awaits confirmation by the state House of Representatives. Arkansas Senate Bill 433 passed in early April and was signed into law April 14.

Supporters of these bills, appealing to the historical influence of the Ten Commandments on the US Constitution, argue they do not violate the separation of church and state. However, it is evident that those putting forward these bills have more than history in mind. Others may be motivated by a desire to rebuild the moral foundation of our nation or to gain the trust (and votes) of those who do.

Opposition from the American Civil Liberties Union and the Freedom from Religion Foundation is no surprise. These groups eschew any attempt to bring God into the classroom. But perhaps more surprising is the opposition to these bills from Christians themselves. Why wouldn’t every Christian want to return our nation to its Judeo-Christian roots? Why not relish the opportunity to provide a moral foundation for our young people?

Republican Steve Unger from the Arkansas House of Representatives is an evangelical Christian and military chaplain but said he could not support the bill. Although Unger agrees the Ten Commandments are part of our “American heritage,” he worries that posting them in the classroom trivializes them and focuses on the “outward trappings of holiness” rather than inward transformation, creating a brand of “cultural Christianity” that bears little resemblance to the Christianity espoused by the Bible.

I am not a politician, but I have built my academic career—and written an entire book—on the premise that “Sinai still matters.” A photo of Mount Sinai has been the home screen on my computer for at least five years. After writing my doctoral dissertation on Exodus 20:7, the command not to take the Lord’s name in vain, I’ve worked to help churches and individuals better understand the ongoing relevance of Old Testament law for the Christian life. Still, I wouldn’t advocate for a bill such as those currently under debate. Why not?

I agree that the moral foundation of our nation is in a serious state of deterioration. I would love nothing more than for a revival to sweep through. But I have concerns about the constitutionality of posting the commands in public school, which could violate the establishment clause. More importantly, I remain unconvinced that posting the Ten Commandments would either repair our nation’s moral foundation or prompt greater faith. To explain my perspective, I want us to consider more closely the purpose and audience of the Ten Commandments.

The Ten Commandments are one of the most familiar passages of the Old Testament, but such familiarity can often breed sloppy theology. We think we know what they mean, so we don’t engage in the careful reading and reflection required to understand them as they were intended to be understood. Two distortions, in particular, tend to plague evangelical approaches to the Ten Commandments.

At a popular level, many Christians are under the mistaken assumption that obedience to the law was how ancient Israel earned salvation under the old covenant—and since we now believe salvation is offered to us by grace through faith in Jesus under the new covenant, the law should be abandoned altogether.

In other words, if the law was how Israelites were saved, then our salvation in Jesus would now replace and supersede it. But if the purpose of the law was not salvation and instead offered a larger vision of how to live in Yahweh’s world, then it might still be valid for Christians today. Those in the former camp might affirm the ongoing value of the Ten Commandments only insofar as Jesus reaffirms them in the New Testament.

A second distortion of the Ten Commandments sees them as based on “natural law,” meaning that they are timeless and universally valid for all people of all time, regardless of the context. While it’s true that the commandments are worded more generically than some of the other Old Testament laws, they are neither timeless nor universal. For example, the command against coveting (in the context of adultery) is directed only at adult males. And the only people who are capable of taking the Lord’s name in vain (Ex. 20:7) are those who have become part of God’s covenant people so that they bear his name in the first place.

Both misconceptions about the Ten Commandments—seeing them as either salvific or timeless—ignore their biblical context and extract them for other purposes. If the commands were salvific, then wouldn’t the Lord have sent Moses directly to Egypt with two stone tablets listing prerequisites for getting rescued from Pharaoh? Instead, all that was expected of the Israelites to demonstrate faith in Yahweh’s promise was to participate in the Passover and pack their bags.

It wasn’t until the Israelites arrived at Mount Sinai and were invited into a covenant relationship with Yahweh that he specified its parameters. The laws were not a means of salvation but a matter of mission. To be the people who represented Yahweh among the nations—those who bore his name and functioned as a kingdom of priests (Ex. 19:6)—they needed to live in a way that was consistent with his character and rule.

The Israelites were not called to be missionaries in the sense of being sent out to teach God’s laws. They were simply supposed to live by them, which would result in the curiosity of others, who would be drawn in to find out more (Isa. 2:1–4). When Yahweh pronounced judgment on the nations through his prophets, they did not berate people for worshiping other gods or breaking the Sabbath. Instead, the nations warranted judgment simply because they were excessively violent toward their neighbors.

The Book of Amos offers a good example of this. Yahweh condemns the Arameans for cruelty against Gilead, the Philistines and Phoenicians for human trafficking, the Edomites for unchecked rage against Judah, the Ammonites for brutality fueled by greed, the Moabites for excessive dishonor of the Edomite king (1:1–2:3). But when the prophet turns to the southern kingdom of Judah, the basis for his condemnation takes a decisive shift:

For three sins of Judah,

even for four, I will not relent.

Because they have rejected the law of the Lord

and have not kept his decrees,

because they have been led astray by false gods,

the gods their ancestors followed. (2:4)

God judged Judah because of Torah violations, such as the worship of false gods. The Israelites knew better. The standard was different for those whom God had drawn into covenant with himself. As recipients of God’s law, they were held to a higher standard.

And what about us today? Obedience to the law helped Israel fulfill its mission to represent God to the nations, and New Testament believers are incorporated into that mission by faith in Jesus (1 Pet. 2:9–10). Therefore, Old Testament laws, including the Ten Commandments, are an important source of revelation for us about God and his purposes in the world. But they were never meant to be held up as a standard for the general public.

If we want a godly example of how to interact with a nation that has lost its moral compass, we might consider Daniel. What can we learn from Daniel about how to steward power in an ungodly empire? After all, as Marvin Olasky has argued for CT, we do not live in ancient Israel but in a modern-day Babylon.

The Babylonian army dragged Daniel from his home along with other Judeans who showed promise. Shockingly, King Nebuchadnezzar elevated him and his friends to government positions. When Daniel arrived in Babylon, we might have expected him to lobby for religious reform or at least to advocate for religious protections for Jews like himself. But while he refused to compromise personally on matters of worship, as far as we know, Daniel did not petition for the Decalogue to be posted in public institutions around the Babylonian empire.

Daniel warned the king of the folly of arrogance toward Yahweh, but he did so with kindness (4:27). Daniel did excellent work and demonstrated wisdom and discernment. Dedicated to the God of Israel, he maintained his personal convictions in the sight of others without trying to change anyone around him—or complaining about the persecution that came as a result.

Beyond Daniel’s example, pastor and professor Mark Glanville has made an excellent case for why posting the commands in public school classrooms may actually signal a failure to love our neighbors well. Pointing to ways the Old Testament law encourages generosity and care for the vulnerable among us, Glanville asks, “Will those Christians who cherish these laws enough to have them displayed in every public classroom also submit to their prophetic call?”

In addition, I worry that by divorcing the commandments from their literary and theological context, we send the message that the God of the Bible is someone who demands obedience without offering himself. Yahweh did not lead with the law; he began by hearing the cries of the oppressed and working to set them free. Shouldn’t we follow his example and do the same?

Instead of working to post our convictions on the walls of public school classrooms, what if we invested in the health of our public schools? What if Christians approached local principals to find out how we could serve? What if, instead of hanging posters, we offered to pick up trash? Instead of lobbying, what if we showed tangible expressions of love, such as sending backpacks with school supplies for impoverished students? What if we volunteered to be lunch buddies for lonely kids? What if we offered to tutor struggling students?

I wonder if many American Christians have lost sight of the heart of Christ’s gospel. After all, John 3:16 does not read, “For God so desired to correct the world that he gave his one and only law, that whosoever obeyed that law would not perish, but have everlasting life.” If we want the children of our communities to experience everlasting life, then our mission ought to be to demonstrate the love of Jesus, not whip them into shape outwardly.

The Bible makes it clear that only our transformation by God’s Spirit enables us to obey his law. Putting it the other way around results in either hypocrisy or a salvation based on our own works.

Carmen Joy Imes is associate professor of Old Testament at Biola University and author of Bearing God’s Name, Being God’s Image, and a forthcoming book, Becoming God’s Family: Why the Church Still Matters.