May 26, 1838, was the start of what we know today as the Trail of Tears, the forced deportation of 16,000 members of the Cherokee tribe. This year, the anniversary falls on Memorial Day, America’s national commemoration for brave soldiers.

But not every solider wears a uniform. Some wield pens occasionally—but not usually—mightier than swords, as one Christian journalist who stood up for the Cherokee learned.

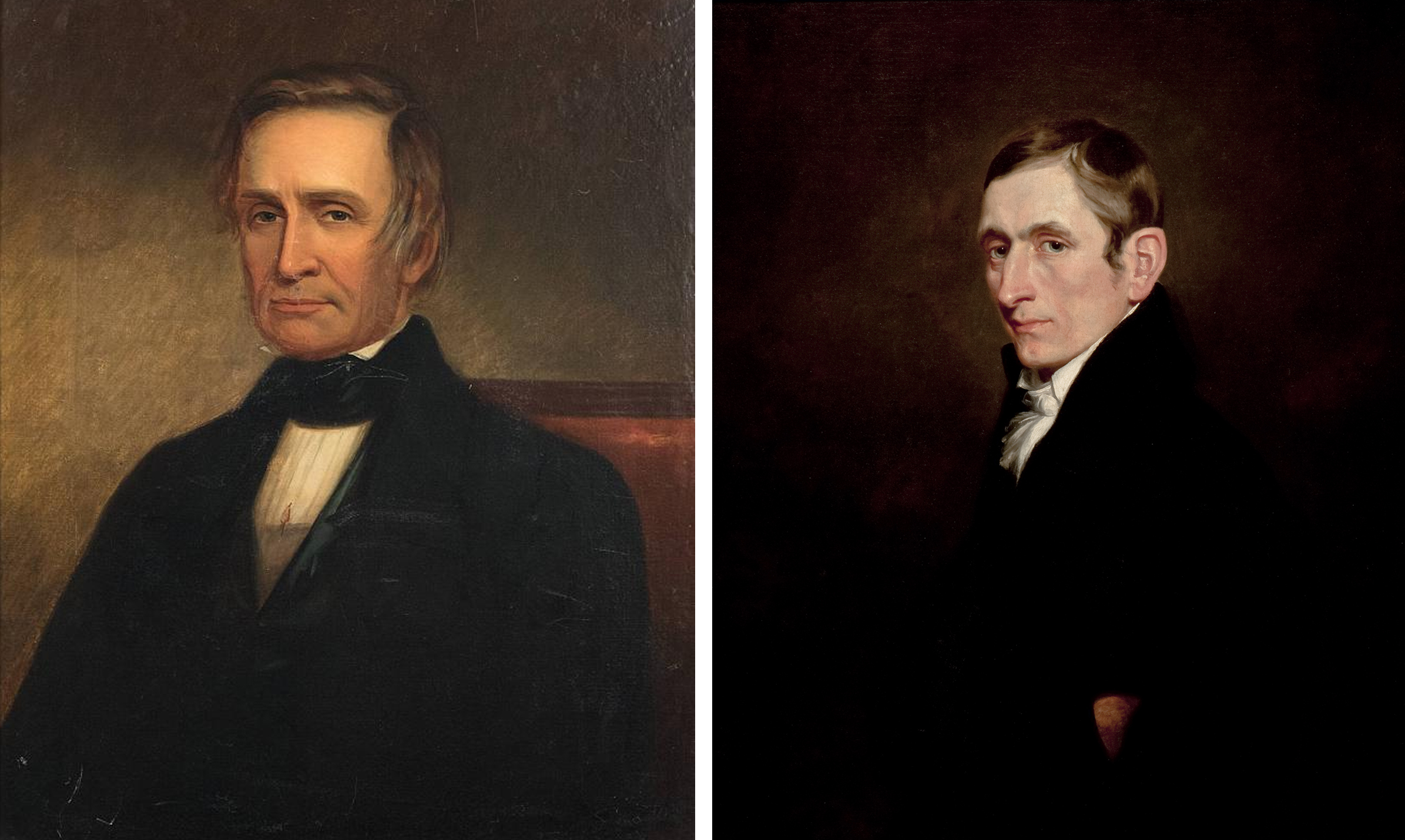

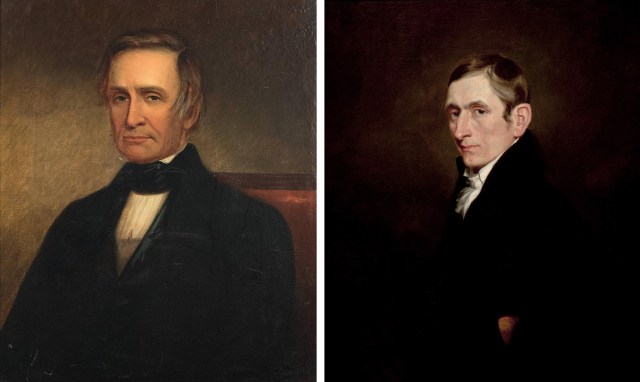

Jeremiah Evarts was born in 1781, eight months before the Battle of Yorktown brought American independence. He graduated from Yale in 1802 and edited the Panoplist, a monthly Christian magazine that later changed its name to Missionary Herald. (Panoplist means someone dressed as a soldier—or equipped with the shield of faith, the belt of truth, and other tools of a reporter as well as a warrior.)

During the 1820s, Evarts served as a missionary to the Cherokee and a columnist for the National Intelligencer, a Washington, DC, newspaper. In 1829, he wrote 24 articles opposing a forced move of the Cherokee from their farms in Eastern states to wilderness across the Mississippi River.

Evarts expressed sympathy for a tribesman scheduled to become “a vagabond, even while standing upon the very acres, which his own hands have laboriously subdued and tilled.” He tried to awaken readers’ sympathy for the Cherokee, “bound to us by the ties of Christianity which they profess … fellow Christians, regular members of Moravian, Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist churches, fellow-citizens with the saints and of the household of God.”

Theodore Frelinghuysen, a first-time senator from New Jersey, read the articles and decided to risk his political future. In 1830, in a Senate packed with orators such as Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and John C. Calhoun debating “Indian removal,” Frelinghuysen spoke up, asking whether the obligations of justice change with the color of skin.

“Is it one of the prerogatives of the white man [to] disregard the dictates of moral principle, when an Indian shall be concerned?” he asked, telling fellow legislators that their plan would “blot the page of our history with indelible dishonor [and] inflict lasting injury upon our good name.”

Frelinghuysen said the cries of the exiled “will go up to God—and call down the thunders of his wrath.” He complained about “oppressive encroachments upon the sacred privileges of our Indian neighbors” and a lack of due process: Has America become “Asiatic despotism, sinking under the crimes and corruptions of by-gone centuries, feeling no responsibility and regarding no law of morality or religion?”

The United States in 1830 had an operating Congress. The debate was lively, but both the House and the Senate approved the deportation plan as Southern Democrats fell in line.

Evarts in the National Intelligencer quoted one congressional leader explaining, “We have succeeded in making the Indian subject a party measure. There may be some chicken-hearted fellows at the North, who will not stand by the party; but we shall carry the measure in both Houses.”

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsThat’s what happened, although a few Southern Democrats resisted. Rep. Davy Crockett of Tennessee said the treatment of the Cherokee was “unjust, dishonest, cruel, and short sighted in the extreme.” He said he had been “threatened that if I do not support the policy of removal, my career will be summarily cut off.” That’s what happened: Crockett, with his political career ended, eventually had a brief military career in Texas at the Alamo.

Other leaders did not want any delays. When a Georgia court condemned to death for murder George “Corn” Tassel, a Cherokee, and others questioned the verdict, Georgia responded by immediately executing him. When Cherokee chief John Ross was preparing to head to Washington with hopes of delaying removal by force, his opponents imprisoned him in a cabin with the decaying corpse of a hanged Cherokee dangling from the rafters.

By then, Evarts was dead: tuberculosis. We have records today of the pleas of Cherokee Christians. One protest stated, “Our cause is your own. It is the cause of liberty and justice. We have learned your religion also. We have read your sacred books. Hundreds of our people have embraced their doctrines. … We are indeed an afflicted people! … Spare our people!”

To no avail: The Cherokee removal deadline became May 1838. The first general in charge of preparation, John Wool, had some compassion. He ordered the purchase of 7,000 blankets, 4,000 pairs of shoes, and 4,000 “yards of assorted cloth goods from New York to distribute among poor Indians.” The War Department said no because the secretary of war, told to make the move as inexpensively as possible, had not authorized the purchase. Wool complained and gained reassignment to the Canadian border.

Some among the Cherokee did not believe America would be brutal. In May 1838, fake news spread through the tribe: The deadline would be extended for two years! They were surprised when soldiers arrived on May 26 and at gunpoint drove them toward wooden stockades, not even giving them time to pack.

A correspondent of The New York Observer, a conservative Presbyterian newspaper, publicized eyewitness reports of families “startled by the sudden gleam of bayonets in the doorway. … Men were seized in their fields or going along the road.”

Private John Burnett, who worked as an interpreter, said, “In the chill of a drizzling rain on an October morning, I saw them loaded like cattle or sheep into six hundred and forty-five wagons and started toward the west. … Many of these helpless people did not have blankets and many of them had been driven from home barefooted.”

Probably about 4,000 Cherokee died on the trail of tears. In 1841, John Quincy Adams said the use of force would be “among the heinous sins of this Nation for which I believe God will one day bring them to justice.”

In 1890, Burnett, 80 years old and still mourning, said, “Let the Historian of a future day tell the sad story with its sighs, its tears and dying groans. Let the great Judge of all the earth weigh our actions.”