Recently on The Russell Moore Show, Russell Moore spoke with singer, songwriter, and author Andrew Peterson about the authors who, by God’s grace, helped hold their faith together when it could have come apart. Listen to the full conversation on our website or wherever you get your podcasts. This excerpt has been edited for clarity and length.

One of the things that I noticed when I was thinking about the authors that I love the most is that almost all of them write in multiple different ways. Novels, short stories, essays, poems—some combination of those four. You as an author do this too, including writing children’s books.

What about in your own childhood? What books mattered to you, and how did you come across them?

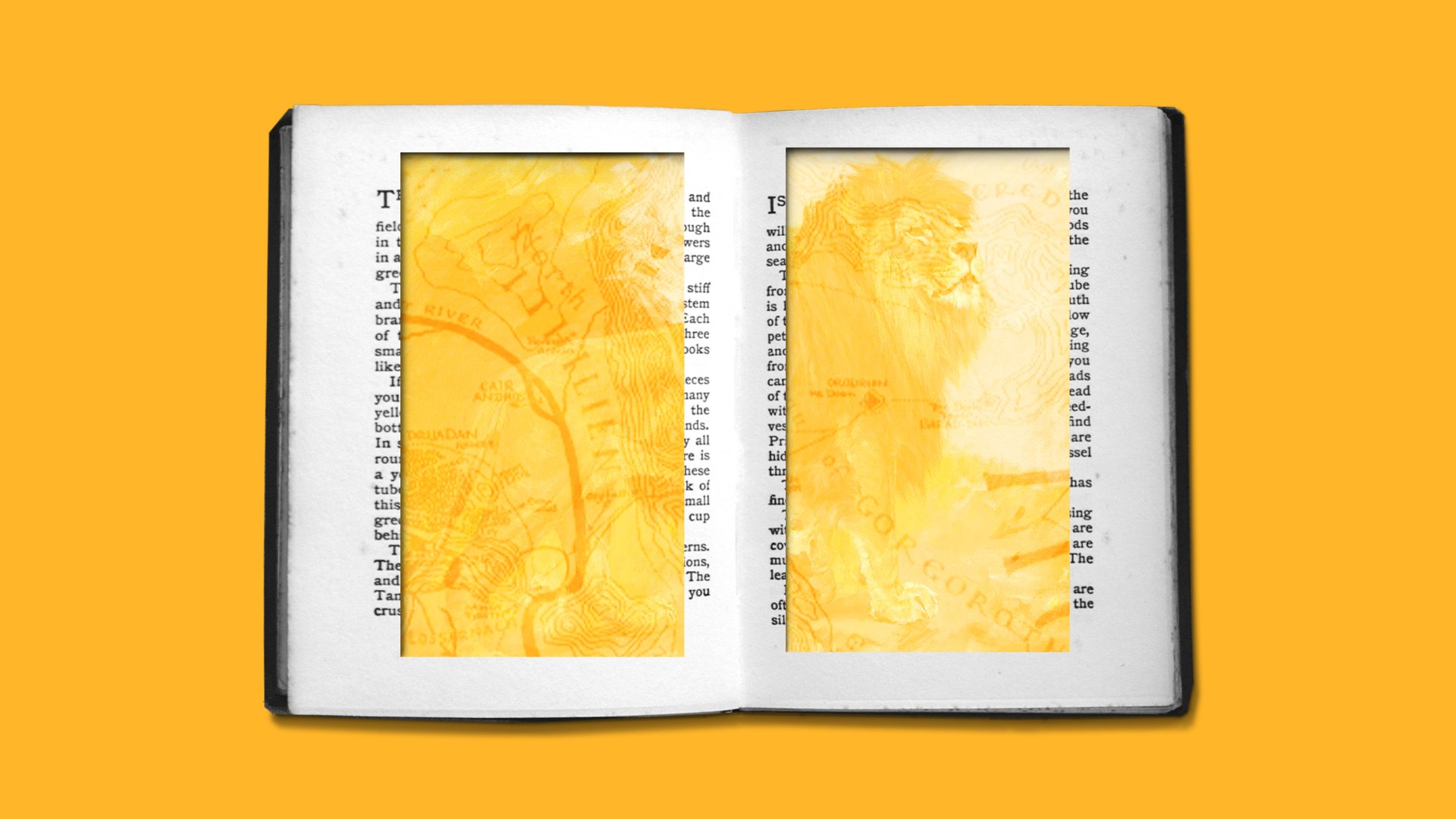

When I was a kid, I was reading a lot of Hardy Boys, The Chronicles of Narnia, [and] Lloyd Alexander’s Chronicles of Prydain and The Black Cauldron (which became a really bad Disney movie). I loved Beverly Cleary, including The Mouse and the Motorcycle.

Then around eighth grade, I begged my dad and mom for a series of fantasy novels called Dragonlance Chronicles, which were these Dungeons and Dragons–adjacent adventure stories. My parents were very nervous because it was the ’80s; the most evil thing you could do was play Dungeons and Dragons. I remember getting in huge trouble because I had borrowed my friend’s Dungeon Masters’ guide. I had the book in my bedroom that I’d borrowed like contraband.

I’ve literally never once played. But my friends did, and I loved the pictures. I was always into drawing trolls and dragons.

It was a big deal that my parents agreed to buy me this series. And man, Dragonlance just lit me up. I loved reading what I see now is really bad fantasy, but at the time it was an escape.

We have a podcast series by my colleague Mike Cosper on the Satanic Panic, Devil and the Deep Blue Sea. One of the things that’s interesting to me is that though my parents were comparatively very relaxed, all around me there were people for whom Dungeons and Dragons was going to lead you right into sacrificing goats. Many of them were suspicious of anything that depicted gods or evil figures. But the same people didn’t seem to have the same problem with Narnia.

We’ve bumped into that with my children’s fantasy book series, The Wingfeather Saga. People that are really upset about Harry Potter give Lord of the Rings and Narnia and George MacDonald a pass. I don’t really know why. I don’t think it’s a bad idea to be careful, but when there is a moral undergirding to a story … In Harry Potter, for example, the power of sacrificial love is the central theme.

What about C. S. Lewis? When did he come into your life?

I liked his books as a kid, but I didn’t always love the fact that they seemed to be trying to teach me something. I’m a pastor’s kid, and I was wary of that; what I wanted was pure story. If I sniffed a Sunday school lesson … I didn’t really fall in love with the Narnia books until I reread them in college.

I was also reading all the time as a kid—except for the required reading. I don’t think that in most ways you and I are “rebellious.” So where does that come from?

The thing that popped into my head is the C.S. Lewis quote:

I thought I saw how stories of this kind could steal past a certain inhibition which had paralyzed much of my own religion in childhood. Why did one find it so hard to feel as one was told one ought to feel about God or the sufferings of Christ? I thought the chief reason was that one was told one ought to. An obligation to feel can freeze feelings. And reverence itself did harm. The whole subject was associated with lowered voices; almost as if it were something medical. But supposing that by casting all these things into an imaginary world, stripping them of their stained-glass and Sunday school associations, one could make them for the first time appear in their real potency? Could one not thus steal past those watchful dragons? I thought one could.

This comes up with the Wingfeather animated series. The team is amazing, and screenwriting is a completely different discipline than what I do—so I’m not writing the scripts, but I’m reviewing them and making notes. There are times when I think the writers think of Wingfeather as a kid’s show written by a Christian, and there will be moments where they’ll try to make a moral point. My most consistent note in the sidebar of the scripts is often “no teachable moments.” This is not a Sunday school lesson. They’re running for their lives; let them run for their lives. Which is not to say that stories don’t teach us. I would hope that if the parents are watching the show, the teachable moment is at the dinner table after it’s over. But that sense of moralizing—I’m allergic to that.

With C. S. Lewis, one of the things that you maybe picked up as being “teachy” actually had the opposite effect on me. For instance, when he would say something like, “Now of course you should never go into an actual wardrobe”—to me that gave a kind of wink-nod, conspiratorial, “You’re in this as we’re going through this story together.”

When I was a teenager and I was about to lose my faith, I found Mere Christianity because I knew Lewis from the Narnia books. And part of what was important to me about that book was not the arguments; it was a similar tone to “You really probably don’t want to go into a wardrobe.”

Did you have a moment similar to that when it comes to Lewis’s nonfiction work?

I remember reading Mere Christianity in college, and I’ve reread it since. You get the sense that he was actually honest. The only reason he was able to write about some of the doubts that we have is because you could tell that he had also experienced those doubts and there was no shame involved. It felt like talking to a friend; his voice is so clear.

I was in the middle of a desolate season when I read Till We Have Faces; it was like God slipped that book under the door.

I had kind of lost my faith after high school and was just casting about. But I was playing music, a language that resonated with me. It was hearing Rich Mullins’s music that was the doorway for me back to rediscovering C. S. Lewis and then rereading Lord of the Rings.

All those authors were multidisciplinary—G. K. Chesterton too. Murder mysteries and books of theology and poems. That was so intriguing to me—there were all these entryways into their work, but you got the sense they were all talking about the same thing.

And my hunch is that’s why those writers have such staying power. It’s because they weren’t just doing one thing.

Then there’s Frederick Buechner. My first book of his was The Eyes of the Heart. I couldn’t believe how good it was. He has a way of constructing a sentence that nobody else really does. That book also came to me at the right time.

What about Wendell Berry?

I discovered Wendell Berry because of a friend who was reading a book of his poems on the road and mentioned Jayber Crow.

That became one of the books that changed my life.

I had exactly the same sort of experience reading Wendell Berry, right around the time I was moving to Kentucky. What Buechner was doing in a solitary way Berry was doing in the context of a community. You had that sense of membership that shows up in the essays, in the poems, in the short stories, in the novels, and it all fit together.

C. S. Lewis gave me a way to think about Jesus. That has never left me. And then Frederick Buechner gave me a way to think about my faith and my story. And then Wendell Berry helps me think about how I live in a practical way, not just in community with my family and my church and my neighbors but with the frogs that live in the pond and the birds that come to the feeder and the plants that are growing in the front yard. When I finish a Wendell Berry book, I end up with concrete changes in the way that I go about my days.