(For the previous article in this series, see here.)

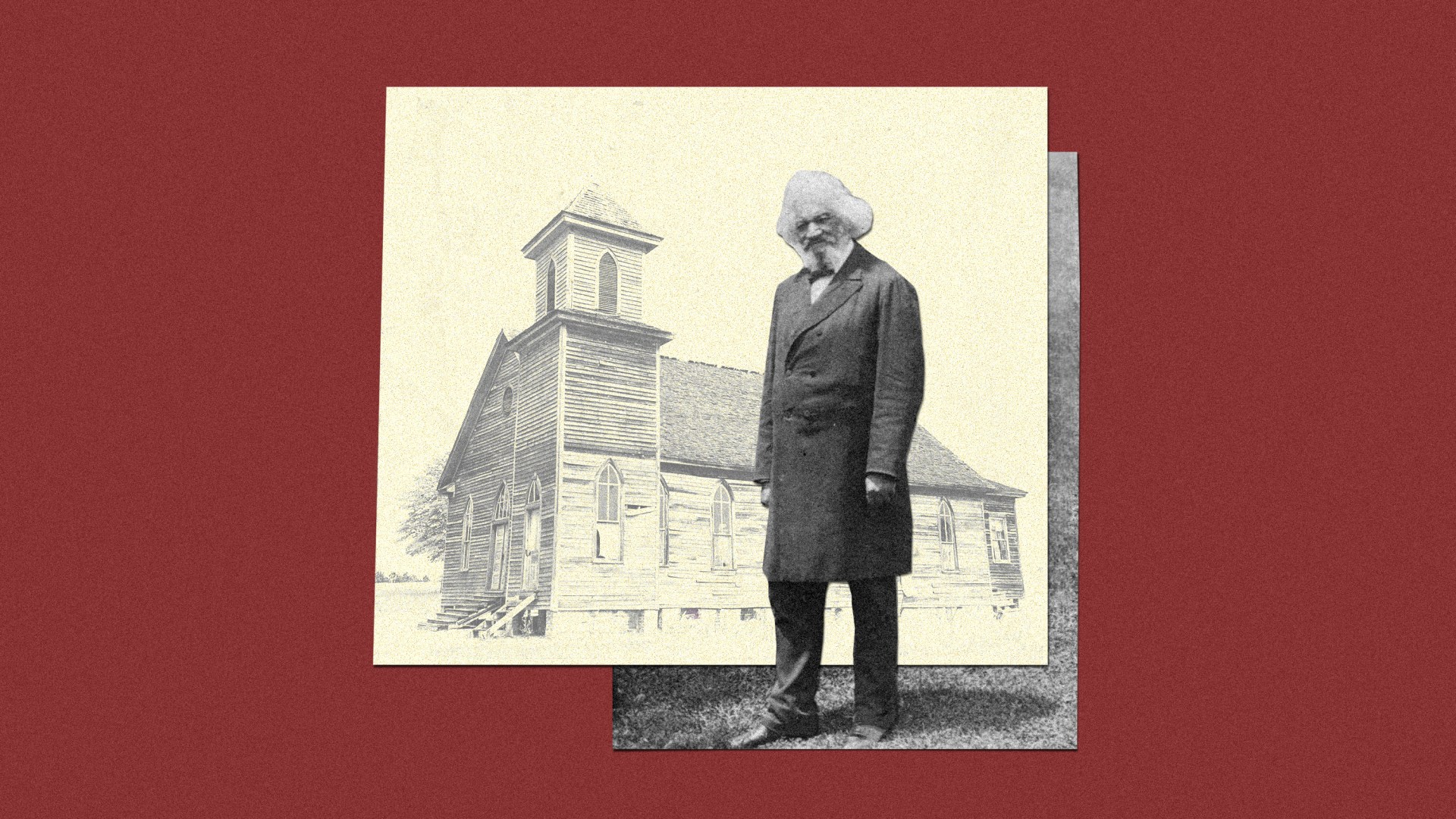

“The negro can go into the circus, the theater, the cars … but cannot go into an Evangelical Christian meeting,” an elderly Frederick Douglass exclaimed in 1885 to a crowd in the nation’s capital. They had gathered to celebrate the 23rd anniversary of the abolition of slavery in Washington, DC, a result of the first emancipation law passed by the U.S. government in 1862. Three years later, in 1865, Union troops ordered the freedom of slaves in Texas on a day that came to be known as Juneteenth, and the 13th Amendment forbade the practice throughout the country.

But for the famed abolitionist, the meeting wasn’t just a celebration. It was also an occasion to critique evangelicalism, a movement with which he had a complicated relationship.

In his last autobiography, Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, Douglass tells the story of how he became a Christian around 1831 while listening to the preaching of a white Methodist minister. After his conversion, Douglass, who was a teenager at the time, was discipled by a slave whom he called “Uncle Lawson.” He writes that Lawson nurtured a love for the Bible in him, set an example of ceaseless prayer, and encouraged the belief that God would one day free Douglass for a “great work.” Lawson also connected Douglass to a fervent community of enslaved Christians who met to worship in seclusion.

Recalling his early days as a believer in Maryland, Douglass wrote he “saw the world in a new light.”

“And my great concern,” he said, “was to have everybody converted.”

But the beauty he found in the gospel was mixed with sorrow when his master, Hugh Auld, discovered the Lawson-led hush-harbor community where Douglass worshiped, and forbade him from attending the meetings. Douglass felt “persecuted by a wicked man” but became hopeful again when Auld himself converted to Christianity in an evangelical revival. Douglass had hoped it would turn Auld into a “more kind and humane” man, as he wrote in his first autobiographical narrative. But instead, Auld “found religious sanction and support for his slaveholding cruelty.”

Douglass’s muddled experience with evangelical Christianity mirrored what many other slaves experienced. Many of them came to faith through evangelicalism and were able to grasp the hope of emancipation—and equality. Yet they also saw white evangelical preachers espouse proslavery doctrines and comfort with tearing apart Black families to uphold the lucrative institution. With this hypocrisy in mind, Douglass famously wrote, “I love the pure, peaceable, and impartial Christianity of Christ: I therefore hate the corrupt, slaveholding, women-whipping, cradle-plundering, partial and hypocritical Christianity of this land.”

Although free and enslaved Black Christians could see the contradictory views held by their white counterparts, they left neither Christianity nor evangelicalism. Instead, they formed their own churches within the tradition—one of which became a home to Douglass after brief stops along the way.

After attending the Lawson-led hush harbor, Douglass was a member of the integrated Methodist community in Baltimore, Maryland. There, he worshiped with other slaves and slave owners, who he mentions were at times viciously violent to the enslaved churchgoers outside of service.

After escaping to freedom in his early 20s, he sought to join a Methodist Episcopal Church in Massachusetts, a state that had effectively abolished slavery decades beforehand. When Douglass arrived in the town of New Bedford, he expected to find a less hypocritical practice of Christianity. But what he saw was another form of degradation: Black congregants separated and seated behind their white counterparts. And their second-class status further reinforced during Communion, in which they were invited to partake after all the white members were served.

Douglass never returned. Instead, he joined a local branch of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church, a Black denomination that was formed in New York City in 1821.

Around the same time, other Black Christians were also joining African American, or as they were called back then, “African” churches. The first ones were formed in partnership with white people who supported separate meeting spaces for African Americans. In the South, some of the first Black congregations in Georgia and South Carolina were formed as African Baptist churches. They were established by preachers, such as George Liele and Andrew Bryan, who were born into slavery. In other parts of the region, enslaved and free Black preachers were also becoming pastors and leading their own flocks.

But after some slave revolts, slaver owners grew suspicious and the Southern Black churches became less prevalent – and independent. White supervision of worship services became more common, leading Black congregants to transform their churches into clandestine gatherings near swamps and hush harbors.

Meanwhile, in the North, the African church movement continued to grow. Black Baptists, Methodists, Presbyterians, and Episcopalians who converted during evangelical revivals formed separate denominations or new congregations, the most prominent of which were the African Methodist Episcopal (or AME) Church, the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, and the African Presbyterian Church.

The churches came about in a variety of ways. Some, like the AME and the African Episcopal Church of St. Thomas, were formed after the founders, Richard Allen and Absalom Jones, refused to accept racism and second-class treatment within the white church. The African Presbyterian Church was organized after free Black preachers attracted large Black crowds with public sermons and formed them into one congregation. Meanwhile, others—like Thomas Paul’s Abyssinian Baptist Church in New York—came at the request of Black congregants who initiated a process to separate from an integrated church.

But whether they worshiped in their own denominations or congregations, these new spaces gave Black believers the ability to live out their faith in a way that affirmed their full humanity. As a result, many churches became hubs for Black abolitionists, aids to those sojourning through the Underground Railroad, and purveyors of a Black evangelical theology that championed the imago Dei.

When Douglass moved to New Bedford, he began gravitating towards the abolitionist movement and the writings of William Lloyd Garrison, the publisher of the anti-slavery newspaper Liberator.

After becoming a member of New Bedford’s African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in 1838, Douglass received his license to preach through the denomination. Thankfully, some of the historical documents we have from this time give us a window into his theology and speeches, which went beyond castigating proslavery evangelicals for their participation in a cruel institution. He also spoke to the heart of the matter: how they view Jesus.

In his 1885 speech at the nation’s capital, Douglass said that “of all the forms of negro hate in the world,” he wanted to be spared from the “one which clothes itself with the name of the loving Jesus.” He then touched on what most Christians know: Jesus associated himself with the poor and the lowly.

Even though the abolitionist was facing a crowd, his words were aimed at evangelist Dwight L. Moody, a white minister who had recently visited Washington. Moody was the most prominent evangelical evangelist of the time, attracting hundreds and thousands to his preaching tours. But when he came to the nation’s capital, he barred Black people from public revival meetings and made separate visits to their churches.

As evangelical Christians, Douglass and Moody would have articulated the main tenet of the gospel: that human beings need to repent and receive forgiveness from God, and be transformed by the Holy Spirit, which comes only through Jesus Christ. But Douglass and many other Black Christians also saw their faith as a call to be fully formed by the life of Christ—who himself was lowly, poor, and despised.

Douglass rightfully understood Spirit-enabled conformity to the image of Christ would require white evangelicals to stop degrading Black people who had occupied a place of disrepute in society. He saw their comfort in doing so as evidence of a malformed Christianity, one that showed outward doctrinal marks but lacked a renewed view of creation that comes from authentic communion with Jesus.

Douglass’s speech in Washington came at a time when African Americans needed help. The Black community was discouraged. They were living under a president who sided with white Southerners on their reluctance to treat Black Americans as equals. They were also suffering from increasing racist violence and marginalization, a societal issue that the Supreme Court’s verdict on Plessy v. Ferguson strengthened.

Douglass saw the same spirit that had animated the cruelty of proslavery theologies being reinvigorated. With this in mind, he issued his critique—not to demean evangelicalism but to invite it not to repeat the sins of the past.

Jessica Janvier is an academic whose focus crosses the intersections of African American religious history and church history. She teaches at Meachum School of Haymanot and works in the Intercultural Studies Department at Columbia International University.