Early last month, a group of 59 white Afrikaners who were given refugee status by President Donald Trump arrived in America on a chartered flight, paid for by US taxpayers, in what may be the most expeditiously processed refugee cases the United States has ever seen.

That ought to be good news, at least compared to the complicated, drawn-out, arduous process most refugees typically endure. But this particular arrival was hotly contested.

You see, on January 20, 2025, Trump signed Executive Order (EO) 14163, his 17th (of 157, and counting) executive order in his second term as president. This EO suspended the US Refugee Admissions Program (USRAP) “until such time as the further entry into the United States of refugees aligns with the interests of the United States.” Eighteen days and 41 executive orders later, he signed EO 14204, granting “admission and resettlement through the United States Refugee Admissions Program, for Afrikaners in South Africa who are victims of unjust racial discrimination.” This is necessary, the order explained, in part because South Africa is “undermining United States foreign policy” and therefore threatening “our interests.”

That was how the Afrikaners came here—and came so quickly and easily. (The average refugee resettlement to the US takes 20 years and almost always involves a long stay in a stopover country—typically in an under-resourced “temporary” camp where people sometimes live for decades with no meaningful work, little education, and few opportunities to meet their most basic needs. It’s also worth noting that, unlike the taxpayer-subsidized flight for the South Africans, refugees from other countries sometimes get travel loans from the United Nations, but they must personally repay those costs.)

This rapid resettlement of one group of refugees while all other refugee-resettlement programs have been suspended raises a lot of questions. For instance, how was the USRAP resettling new refugees in May if the program was suspended in January? What US interests are Afrikaners able to serve that every other refugee from every other country is apparently unable to help? And what is the moral calculus that ranks the value of an Afrikaner’s life so far above the lives of people from Myanmar or Ukraine or Sudan or Afghanistan or Haiti or Venezuela?

To be very clear, the problem is not that South Africans were granted refugee status. The problem is that no one else is receiving the same welcome.

Unfortunately, that’s not the issue under wide debate. The administration’s double standard here is so glaring that folks are busy arguing about whether the South Africans are really persecuted enough to merit our sympathy.

On the right, you have pundits trying to explain that things really are bad in South Africa. And while there’s no denying that the country has a high violent crime rate, the idea that Afrikaners are being targeted is a point of reasonable disagreement.

Meanwhile, on the left, some refugee agencies are refusing to resettle the Afrikaners who were admitted, describing this as an act of conscientious objection. In fact, the Episcopal Church announced that it will end its four-decade refugee-resettlement partnership with the US government over this admission decision.

The truth is, when we’re debating whether enough Afrikaners have been murdered to allow them to flee to our country for safety, we’ve lost the moral thread. Again, the problem isn’t that these South Africans were welcomed to America. It’s that only these South Africans were welcomed to America while people in danger of war and persecution in other countries have been categorically locked out.

But it shouldn’t be surprising that we’re having such a misguided debate. This conversation is the natural result of an administration uninterested in due process, the rule of law, and the blind justice of Lady Liberty. Unjust systems that dispose of even the pretense of equality result in ever-escalating dehumanization. They incentivize selfish ambition instead of care for the least of these—and disregard those who have nothing to offer but their need. After all, in a dog-eat-dog world, you’d better be at the top of the pack.

At least one recent Afrikaner arrival was willing to make that moral logic plain, even if Americans prefer to ignore it. “I kind of need to, you know, put my oxygen mask on first,” he told The Washington Post, explaining that it wasn’t for him to say whether or not the US refugee process, which had worked to his advantage, should be restored for anyone else.

Our debate is also confused by what is objectively a masterstroke of political rhetoric by the president. Trump campaigned on closing the border to illegal immigration and strengthening border security, goals that enjoy broad support among the American public. But he’s pursued that end partly by collapsing traditional distinctions between different classes of immigrants—asylum seekers, economic migrants, and refugees—to often-cruel effect. When the Trump team speaks, these words are synonyms for each other and for “illegals.” Each term is just a different way of describing people who are stealing your jobs and raping your women and destroying your culture.

And make no mistake: The Biden administration blurred lines and collapsed categories too. Under former president Joe Biden’s watch, people flooded across our southern border and wrongly claimed asylum. The asylum program is supposed to be reserved for a unique class of immigrants subject to persecution in their home countries, but it became an escape hatch for millions seeking a better life—and the Biden administration let it happen instead of seriously pursuing reform.

Those migrants, many of whom were simply seeking economic opportunity or trying to escape gang violence, are now being demonized by conservatives angry about the border chaos—just as the Afrikaners who got a special dispensation under Trump are being demonized by progressives angry about the unfairness of this exception. In both cases, the problem is not that these people were able to come to America. The problem is the disorder and injustice of the entire system.

I vehemently oppose ending the refugee program for reasons inextricably tied to my faith in Christ. But there is a sort of utilitarian logic to Trump’s initial decision. I’ve heard reasonable arguments for beginning immigration reform with a total shutdown of migrant entries. That kind of hard-line border policy, consistently applied, strikes me as heartbreaking, impractical, and even bad for US interests due to its hits to our soft power and our economy. But it is at least consistent, and consistency is often a hallmark of justice.

As the Afrikaner admissions have made unmistakably clear, consistent reform is not what this administration is doing. If there’s consistency here, I don’t think it’s the consistency of justice. After all, what is it that makes the Afrikaners different from other prospective refugees? Even if the grimmest interpretations of South African crime statistics are true, Afrikaners are not the single-most-persecuted people group on earth.

But they are white, share many Western social and cultural values, and speak English. Put more plainly, they aren’t too foreign, and from the moment they arrive on American soil, they can pass for your average American farmer. Or in the words of a Trump administration official, Deputy Secretary of State Christopher Landau, they’re “quality seeds” who will “bloom” in the US.

Obviously we cannot give every needy person in the world refuge, but that’s precisely why the process needs to be transparent and free for all to pursue.

Are no other people who hope to come to America “quality seeds”? I can think of a few, like Kevenson and Sherlie, the legal Haitian immigrants who live near me in West Texas and are now at risk of deportation. Or Carol Hui, a hardworking waitress who has raised her family in the US for more than 20 years. Or Sofia, the four-year-old whose life was threatened by the deportation notice her family received, because she requires constant specialized medical care. We can’t yet imagine how Sofia might blossom.

These are all quality seeds because they are all human, all made in God’s image, all people for whom Jesus died. Many of them, including Kevenson and Sherlie and Carol, are Christians too, fellow members of the body of Christ. Why is there not more outcry from the American church on their behalf?

I know the answer, of course. Most of us live seemingly untouched by immigration. The delivery drivers who drop groceries at our doors are almost invisible. And we’re human too, with all the weakness that entails. It’s hard to care very deeply or for very long about problems we don’t experience. We’re busy and distracted and have lots of things to worry about before we get around to questioning the political rhetoric from our own side.

While I can explain away our silence in a thousand innocuous ways, none sit well with my soul. And I can’t ignore how it’s perceived by people outside the church.

Take the example of a writer named Joel Mathis, who argued in a recent essay that politically conservative, white American Christians don’t care about religious liberty protections (including refugee admissions) for people who aren’t like them. “When conservatives talk about ‘religious liberty’ what they often mean is ‘white Christian privilege,’” Mathis charged. “The MAGA right expects the U.S. government to defer to Christian sensibilities, except when those sensibilities work for the protection of brown people.”

I know, I know. We have a million objections to such a reductive assessment—not least that in recent years it seems as if everything and everyone (even algebra!) has been deemed racist at some point by someone on the left. But I think Mathis is being sincere, and though I want to tell him that he’s wrong, I can’t deny the weight of the evidence in his favor. Why only the white Afrikaners?

If Kevenson and Sherlie, whose story I told a few weeks ago at CT, are forced to return to Haiti, they will be prime targets for kidnappers because of their connection to rich American Christians. “If they don’t pay the ransom, they can expect to be covered in plastic bags or tires, which will then be set on fire,” explained my friend, Kim Snelgrooes, who sponsored their emigration to America. Why wouldn’t we welcome them too? Even on a purely utilitarian level, they are adding value—working jobs, paying rent and taxes, delivering services—not draining resources.

Or consider the Iranian Christians who were deported by the US to Panama earlier this year. They may be sent back to Iran, where they would likely be killed for their conversion to Christianity. Are their lives worth less than mine or yours or the Afrikaners’?

When Christians do not call such injustice by its name, our silence shouts to a culture already suspicious of our faith and ethics—already primed to summon up historical examples of Christians checking our values at the door to public life, justifying injustice or rationalizing compromise.

I can’t undo Trump’s executive orders or stop anyone’s deportation or open America’s gates to refugees from more countries than one. But I think it’s important to speak up anyway, to protest compassion unequally applied. To explain why, let me tell you a story.

In May of 1939, the St. Louis, a German transatlantic liner, sailed from Hamburg to Havana. On board were 937 passengers, almost all Jews whose American visa applications were in process. The plan was to stop over in Cuba until their final approvals were issued. En route, it became clear that Cuba would not admit them. And then they were turned away from America too, denied entry while they were so close to Miami they could see the lights of the city, flickering across the dark sea. They returned to Europe, where 254 of them would die in the Holocaust.

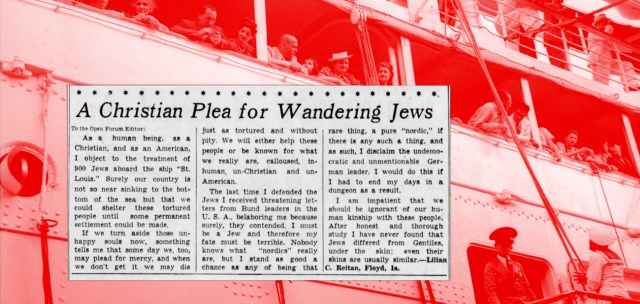

Illustration by Christianity Today / Source Images: Getty,

Illustration by Christianity Today / Source Images: Getty, That same year, far away from the coast and the halls of power lived a Christian woman named Lilian Reitan. She could do nothing about the fate of the Jews aboard the St. Louis, but she spoke about their plight to people she knew and registered her dissent from the US decision to deny them entry in a letter to the editor of her local paper, Iowa’s Des Moines Register.

“We will either help these people or be known for what we really are, calloused, inhuman, un-Christian and un-American,” Reitan said on June 11, 1939. It’s clear that her defense of the Jews was personally costing her, for in the letter she recounted receiving threats as a result of speaking out.

History doesn’t have much else to say about Reitan, and I suppose it could be said that her letter didn’t matter much. The Jews still were sent back to Europe to their deaths.

But 86 years later to the day, her words stand out to me like a pinprick of light in a sea of darkness. She was among the Christians who vocally opposed the fearful, cold-hearted, and spineless decision that sent hundreds of Jews away to die. Reitan’s words are an Ebenezer to me: a wilderness signpost reminding me that God’s empowering faithfulness can help us discern the narrow way (Matt. 7:13) in a world gone mad (2 Tim. 3). The Spirit can give us the courage to speak up for and in his character and truth (2 Tim. 1:7).

As both a follower of Jesus and citizen of America, Reitan exemplified this courage. She could not have expected to change the world with her letter, yet she still felt a duty not to be silent before such rank injustice. Her dual care for the lives of the Jews in danger and the soul of her country reminds me of the prophet Isaiah’s explanation of his hard preaching to his people: “Because I love Zion, I will not keep still. Because my heart yearns for Jerusalem, I cannot remain silent. I will not stop praying for her until her righteousness shines like the dawn, and her salvation blazes like a burning torch” (62:1, NLT).

On the anniversary of her letter, I pray we carry her legacy forward. The course of history may appear to be unchanged, and innocent people—maybe even we ourselves—may be chewed up by the ungodly machines of injustice. But as one Bible paraphrase says, “Men and women who have lived wisely and well will shine brilliantly, like the cloudless, star-strewn night skies. And those who put others on the right path to life will glow like stars forever” (Dan. 12:3, MSG). That’s the example left by Lilian Reitan, and that’s what we followers of Jesus must do now for future generations.

“This is the way; walk in it,” God says to us when we are unsure where to turn (Isa. 30:21). Even if the world walks one way, we can choose to go another. Even if it seems to matter very little, we can raise our voices anyway. Even if everyone around us is falling in line to an earthly ruler, we can bow only to the King of Kings.

Carrie McKean is a West Texas–based writer whose work has appeared in The New York Times, The Atlantic, and Texas Monthly magazine. Find her at carriemckean.com.