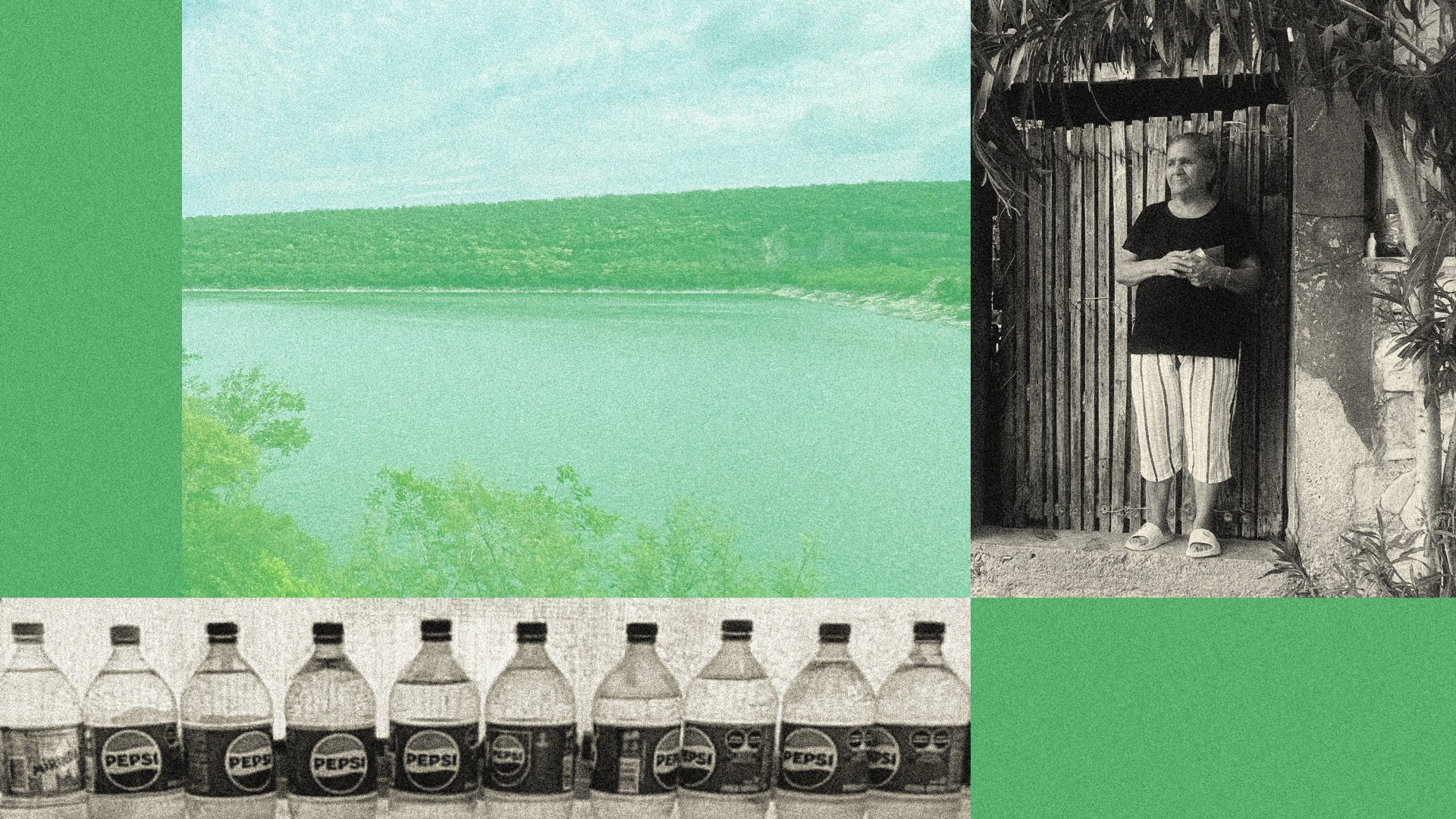

Plastic bottles may be the closest thing to decorations in Magdalena Reyes Valderrama’s three-room home in northeastern Mexico. She’s hung a clock in the pink-walled walkway. A TV sits on a tablecloth depicting oranges. Laundry that the 100-degree heat has long since dried hangs on clotheslines and occasionally flutters in the breeze.

A brittle plastic chair sits here, and a solitary sock lies there. A campaign poster advertises current Mexican president Claudia Sheinbaum Pardo. When Reyes is nervous, she reaches for the nearest available cloth, her grandson’s T-shirt. She folds it and uses it to slap her right shin. Sometimes, she uses it to wipe her tears. Lately, life hasn’t played out as she hoped it would.

Reyes, now 73, met her accordion-playing husband as a teenager. They had seven children and lots of fun, attending party after wedding after quinceañera. She didn’t attend much school growing up, but her husband supported their family. He never hit her, she says. Then he died of lung cancer in 2017 the year before their 50th wedding anniversary.

That death sent Reyes briefly to work for the first time. Now she survives on a pension of 3,000 pesos ($158 USD) per month. She owns her house, but money goes fast. Electricity to power the home’s three box fans costs 350 pesos a month. Her groceries—oil, salt, eggs, tomatoes, onions, rice—cost at least 500 pesos a month, so she eats two meals a day at the government’s meal program for seniors.

What else does she wish she could buy? Reyes pauses and looks away. She takes the folded T-shirt and wipes her eyes with it. Meat. Steak. Kentucky (the chicken of Kentucky Fried Chicken fame).

When she does cook, gas to heat her food costs 200–300 pesos. She can’t afford the gas to heat bath water, so she uses an immersive water heater, a footlong piece of metal that turns hot when its plugged in. The heat melts the handle and electric cord, so she’s had to buy three of the devices in the past year, 150 pesos each time.

Another cost is the water itself, the reason for the plastic bottles on the foyer windowsill and 22 other bottles on a cement ledge. These, along with two large metal vats, a handful of buckets, and a 750-liter tank beneath a statue of Mary, compose Reyes’s teammates in her relentless quest to make sure her household of seven has enough water.

At 7 a.m. on Mondays, Tuesdays, and Wednesdays, she starts running the tap, filling every vessel she can find. Ideally, this will quench the family’s thirst, sanitize their house, and wash their dishes, clothes, and bodies over the rest of the week. Reyes and the other 390,000 residents of Ciudad Victoria, a city that rests just over 1,000 feet above sea level and is nestled between two mountain ranges, do not take water for granted.

Ciudad Victoria is the capital of Tamaulipas, the northeastern Mexico state nestled just below the Texas border. It’s also the only northern state not experiencing drought—this year. From 2021 to 2024, local government officials rationed water for households and cut it for crops, measures that led residents to protest and left companies facing operational challenges.

A year ago, 80 percent of Tamaulipas faced water shortages. Then Tropical Storm Alberto watered the area, and that’s evident in an explosion of leafy plants, bushes, and trees. Nevertheless, the lush flora belies harsh truths. Vincente Guerrero Dam, which sits about 25 miles outside the city and supplies it with 70 percent of its water, sits at only 60 percent capacity.

Padilla, a town of 13,000 is adjacent to the dam. The government in the 1970s flooded Padilla’s original location and moved its infrastructure several miles away. The community is so evangelical, local Baptist pastor Juan López López happily points out, that the government constructed the evangelical church (not a Catholic congregation) when it rebuilt the town.

Padilla residents rely on local wells for their water, but they do need the dam. López’s household has water every day, though not at all hours. Next to his house sits a multicolored skiff. When the water in the dam is plentiful, he uses his boat to catch thousands of fish. Now, with the dam short hundreds of thousands of gallons of water and with an increase in carnivorous fish, his livelihood has taken a hit. “With the compassion of God,” López said, “we are living in the last days.”

Outside Tamaulipas, Mexico’s inland northern states are enduring extreme drought, and the country’s water reserves are at historic lows. Animals die of thirst. Farmers in Baja California, Sonora, Chihuahua, Coahuila, and Nuevo León, the other states that share a border with the US, consider giving up.

Their Texan counterparts also are troubled, and politics has taken over. The US has demanded its neighbor make good on a treaty whereby Mexico “must send 1.75 million acre-feet of water to the US from the Rio Grande every five years.” That’s over 570 billion gallons. Mexico has said it cannot keep up with deliveries because of the drought. In the five-year cycle that concludes in October, Mexico has so far sent less than 30 percent of the required water.

In April, US president Donald Trump threatened to hit Mexico with sanctions “because Mexico has been stealing the water from Texas Farmers.” But Chihuahua governor María Eugenia Campos said, “We can’t give what we don’t have. No one is obligated to do the impossible.”

Others say Mexico could do more for a “foreseen crisis” that has persisted for years. In 2002, about 100 American farmers used tractors to block a bridge on the border to demand that Mexico pay a long-standing water debt to the United States. Mexico has not addressed its water challenges, as countries like Australia with significant arid territory have done. In part because of the expense, Mexico has only four desalination plants. (Last year, Tamaulipas did lease some desalination plants from Dubai.)

Mexico “does not take sufficient advantage of wastewater reuse, which can be used to recharge aquifers, for consumption in industrial facilities, for agricultural irrigation or for urban use,” reported one website, Global Issues, in 2023. Numerous water-reuse plants either are inefficient or have improperly maintained facilities, meaning the country has less water to use.

Further, Mexican farmers have increased the size of their farms while relying on aging and inefficient irrigation infrastructure. “I think all of us, those of us who farm, are aware that we are wasting a lot of water,” Fidel Hidalgo Tarano, a farmer, told PBS News, but “a sprinkler irrigation system or belt system … takes a lot of money.”

Mexico ultimately responded to Trump’s comments by agreeing to send water in the next six months, a promise that, if delivered upon, would be close to more water than the country has delivered to the US in the past four years. In January, the Tamaulipas government announced a $200 million plan to “modernize and upgrade” 200 kilometers of irrigation canals. A Ciudad Victoria aqueduct is currently in its bidding phase.

Meanwhile, the nonprofit The Bucket Ministry has distributed water filters to close to 10,000 Ciudad Victoria residents. Reyes’s household uses one. With 5.2-gallon (20-liter) jugs of filtered water selling for 17 pesos, family members had previously drunk water directly from the tap even when it gave them headaches or diarrhea.

Filters sometimes lead to church relationships. Two ministry leaders who attend evangelical church Amor Viviente—Living Love—helped Reyes’s tighten her filter correctly. They later sat and prayed with her for an hour and talked about her late husband and her mother, also deceased. She dropped her grandson’s T-shirt and opened her palm to accept a tiny seed symbolizing the genesis of faith.

Other Ciudad Victoria residents said the situation is out of their hands. One, Daniel Franco does not have a deed for the land he lives on with family members. They have no running water and fill their 450-, 200-, and 100-kiloliter tanks (a kiloliter is 264 gallons) and two smaller tanks with water from a city truck. But the truck comes only every other month, with no announcement of departures from schedule.