In this series

(For previous articles in this series, see here, here, and here.)

Philosophy professor Evan Thompson, who defines himself as “a good friend to Buddhism,” is also a critic of “Buddhist exceptionalism”: “the belief that Buddhism is superior to other religions in being inherently rational and empirical … a kind of ‘mind science’” that’s “based on meditation.”

Buddhism, particularly in its Zen variation, has gotten a great amount of press as a way of experientially finding one’s “true self,” with a typical article stating, “Meditation Is No Fad. It Could Make Your Career.” Major League Baseball’s television network between innings shows clips of sweet plays under the heading “Baseball Zen.”

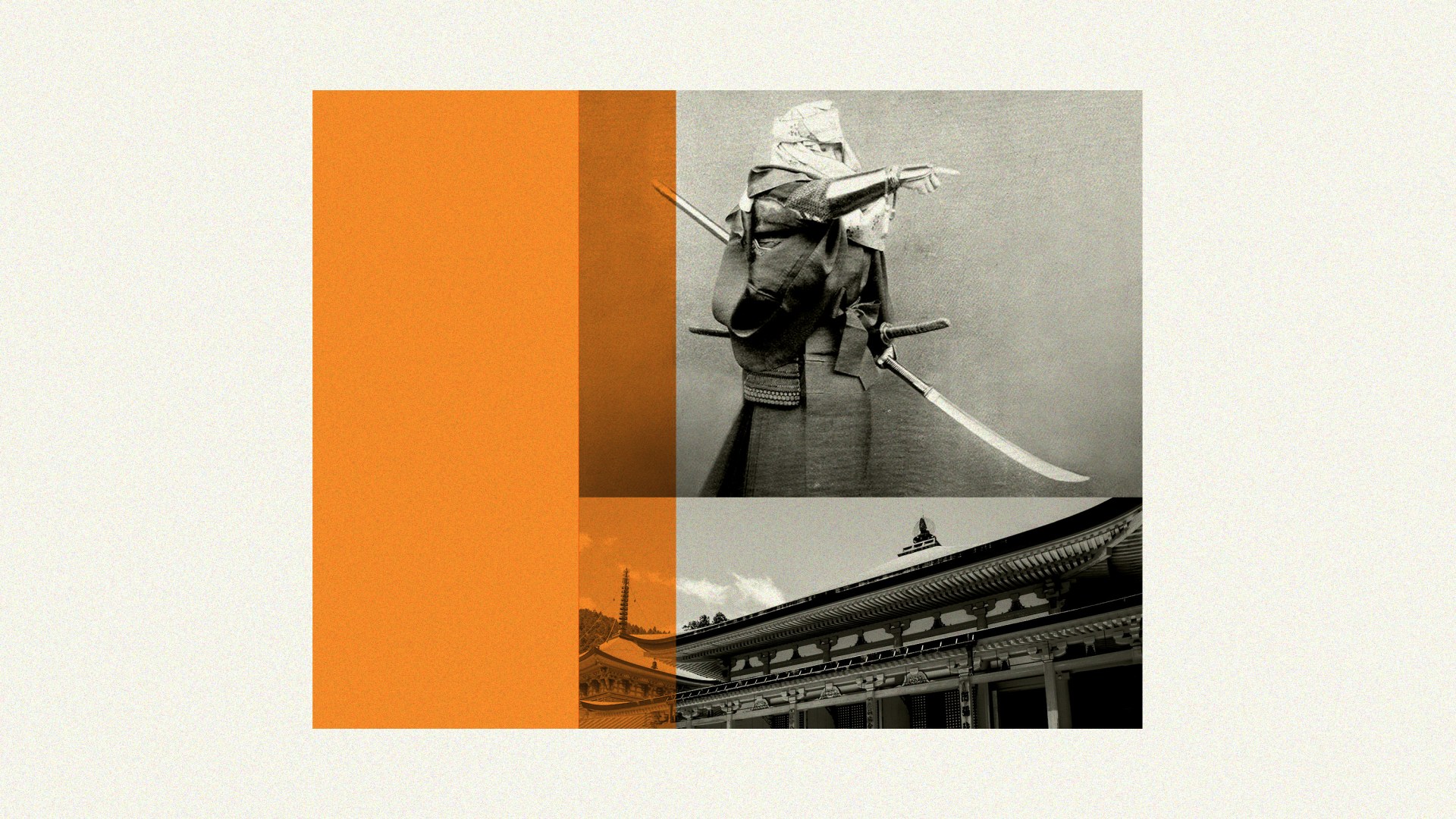

And yet Methodist-turned-Buddhist Brian Victoria shows how Zen Buddhist priests during World War II taught Japan’s military leaders to be serene about killing others and, if necessary, themselves. As samurai warriors in previous centuries found Zen’s mind control useful in developing combat consciousness, so kamikaze pilots visited Zen monasteries for spiritual preparation before their last flights.

Some Buddhists taught that life is unreal, so we should not be attached to it. D. T. Suzuki, who taught at Columbia University in the 1950s and became the prime spreader in America of Zen’s mystique, stated in 1938 that Zen’s “ascetic tendency” helped the Japanese soldier to learn that “to go straight forward in order to crush the enemy is all that is necessary for him.”

This was the latest curve in a long history. Japanese Buddhists built a power center on Mount Hiei, which overlooks Kyoto, Japan’s capital from 794 to 1868. Buddhist armies based on the mountain became known for overthrowing emperors at will. Nine hundred years ago Emperor Shirakawa listed the “three things which I cannot bring under obedience: dice, the waters of a rushing river, and the priests on Mt. Hiei.”

One historian of Kyoto, Gouverneur Mosher, noted that “Buddhism did not retard war but rather promoted it.” Brian Victoria and others do not say that Buddhism leads to violence, but they also say it does not necessarily curtail it. Buddhists can be unattached to war, but they can also be unattached to peace.

For example, in the 15th century two Buddhist armies of about 100,000 men each fought for 10 years with Kyoto as the battleground. The city was destroyed. Then came more civil wars that culminated in 1571 when the armies of Japanese strongman Oda Nobunaga burned 300 Tendai temples and killed thousands of those priests.

Nonattachment can cut both ways.

That’s particularly true because Buddhism is exceptional in one way: Buddhists typically do not pray as Jews, Christians, or Muslims pray, because they turn their devotional meditations inward rather than outward. A leader at one Buddhist meditation center I visited said, “Take your glasses off.” I was not to read but to look within.

On Mount Hiei overlooking Kyoto, where Buddhist armies once ruled, monks I met there were trying to achieve nonattachment through Jogyo-do (constant walking). They also meditated for long stretches while fasting, drinking only a little water, and trying hard not to fall asleep. As one monk explained, “If we can remove the desire for food or sleep, we can get closer to the goal of leaving behind all desire.”

Mount Hiei was also the home of elite monks supposed to walk for at least 18 miles a day for 100 days up and down the mountain’s steep slopes. Others, wearing straw sandals, tried to do 1,000 days of walking 50 miles a day. (The monks I asked were vague on how often this was done over the centuries.)

Four short articles on Buddhism only scratch the surface. When I traveled to Japan, the country with the fourth-highest number of Buddhists, Buddhism changed for me from a strange religion with millions of adherents to one interwoven with the lives of particular faces in the crowd. One was a Japanese woman in her 40s with a mottled face, freckles, and some bruising under one eye.

She and others at a Buddhist temple on Mount Koyasan told me how her parents divorced when she was young and how neither wanted to take care of her. She was the fifth and youngest child, with grown-up brothers and sisters who had also abandoned her. Sent around to the homes of various relatives as half maid, half slave, she tried to have herself committed to an orphanage, but those who mistreated her would not allow an action that would bring public shame.

Hurt further by a hard marriage, she and her son, a toddler, began coming to the temple on a beautiful hill in central Japan about a two-hour drive from the crowded streets of Osaka. She believed she could find relief from her pain on a cool Saturday evening by entering a frigid river, her hands clasped before her. She wore a white robe, indicating purity, and threw handfuls of salt into the water as another purifying gesture.

She began chanting names of Buddha, fast, loud, seemingly without stopping for breath. She let out a scream (“VEE-AYE!”) and stood chanting for ten minutes. She later said that during that time she felt Buddha enter her body. She was numbing herself physically and hoped to numb herself emotionally. Seeking nirvana means seeking the elimination of individuality, but it also means hoping to attain a state where there will be no more pain.

One reason Buddhism gets a great press is because its adherents say it’s a nonreligious religion. But as Evan Thompson notes, the question of faith is inescapable in all belief systems, including Buddhism: “Buddhist faith is trust or confidence in the teachings of the Buddha, and trust or confidence in the possibility of awakening (bodhi) and liberation (nirvāṇa).” The Buddhist bottom line is that we don’t need a savior: If we work at it enough, we can save ourselves.

Readers seeking further enlightenment might turn to CT’s 2023 “Engaging Buddhism” series. In it, Angela Lu Fulton observed, “While Westerners view Buddhism as a philosophy, Paul De Neui, a former missionary to Thailand and professor of missiology at North Park Theological Seminary, noted that this concept isn’t embraced by Buddhists in the East, who see Buddhism as a cultural identity. This means they are Buddhists because their parents are Buddhist.”

She also noted, “When Buddhism entered different countries, the religion’s elasticity allowed it to integrate with local religions. Because it rarely challenged local norms, many could easily accept Buddhism alongside their existing faiths. This practice of syncretism led the religion to look quite different depending on the country. In China, Buddhism was mixed with Daoism and traditional ancestor worship. In Cambodia, its cosmology includes ghosts and spirits, ancestors and Brahma deities.”

Bottom line: “By combining with local religions, Buddhism created a strong bond with people’s nationalities. Often when trying to minister to Buddhists, Christians find that the greatest barrier to evangelism is the mindset that ‘to be Thai (or another nationality) is to be Buddhist.’”