In this series

(For previous articles in this series, see here and here.)

Theravada Buddhism, the original variety, can be high-pressure: Become an arhat, a spiritually enlightened person who has replaced all desire. No emotion: Become indifferent to everything. One percent of Americans are Buddhist, and one-third of those are Theravada. Like Orthodox Jews, Theravada Buddhists don’t go with the flow of standard American life.

Given how hard it is to be indifferent, it’s not surprising that Buddhist expansion 2,000 years ago ran into a wall. Many people did not want nonattachment if it meant a farewell to love. In practice, even Buddhist monks often found they made little progress toward eliminating desire. Ordinary people could make even less. This faith had limited appeal.

Religions compete for adherents, so it’s not surprising that innovative Buddhists developed the concept of bodhisattvas, enlightened beings who could have attained nirvana but purposefully chose to put it off to help others reach it more quickly than they otherwise would. The origin of this belief—that faith in a self-sacrificing bodhisattva is essential—is lost in the mists of time, but speculation abounds.

For example, British scholar Alan Bouquet, describing “Christian Influences on Early Buddhism,” wrote that from AD 50 to 200 some Buddhists learned about Christianity and introduced into Buddhism a new ideal of serving others, not just concentrating on their own spiritual progress: “The bodhisattva must sacrifice his or her possible attainment of release into identity with the Absolute, for the sake of others.”

The new Buddhism, called Mahayana (“great way”), developed many variants over the years. For example, in the 12th and 13th centuries, some Japanese Mahayana Buddhists gravitated to zazen (meditation). These became known as Zen Buddhists, who taught that the faithful should pay no attention to rational thought processes. They came up with famous Zen questions such as “What is the sound of one hand clapping?”

The goal is to force thinkers to conclude that rational thought is inadequate. One famous Christian medieval question—“How many angels can dance on the head of a pin?”—was an attempt to produce the opposite of mysticism. Students were to think through the problem and conclude that an infinite number could fit since angels are incorporeal spirits.

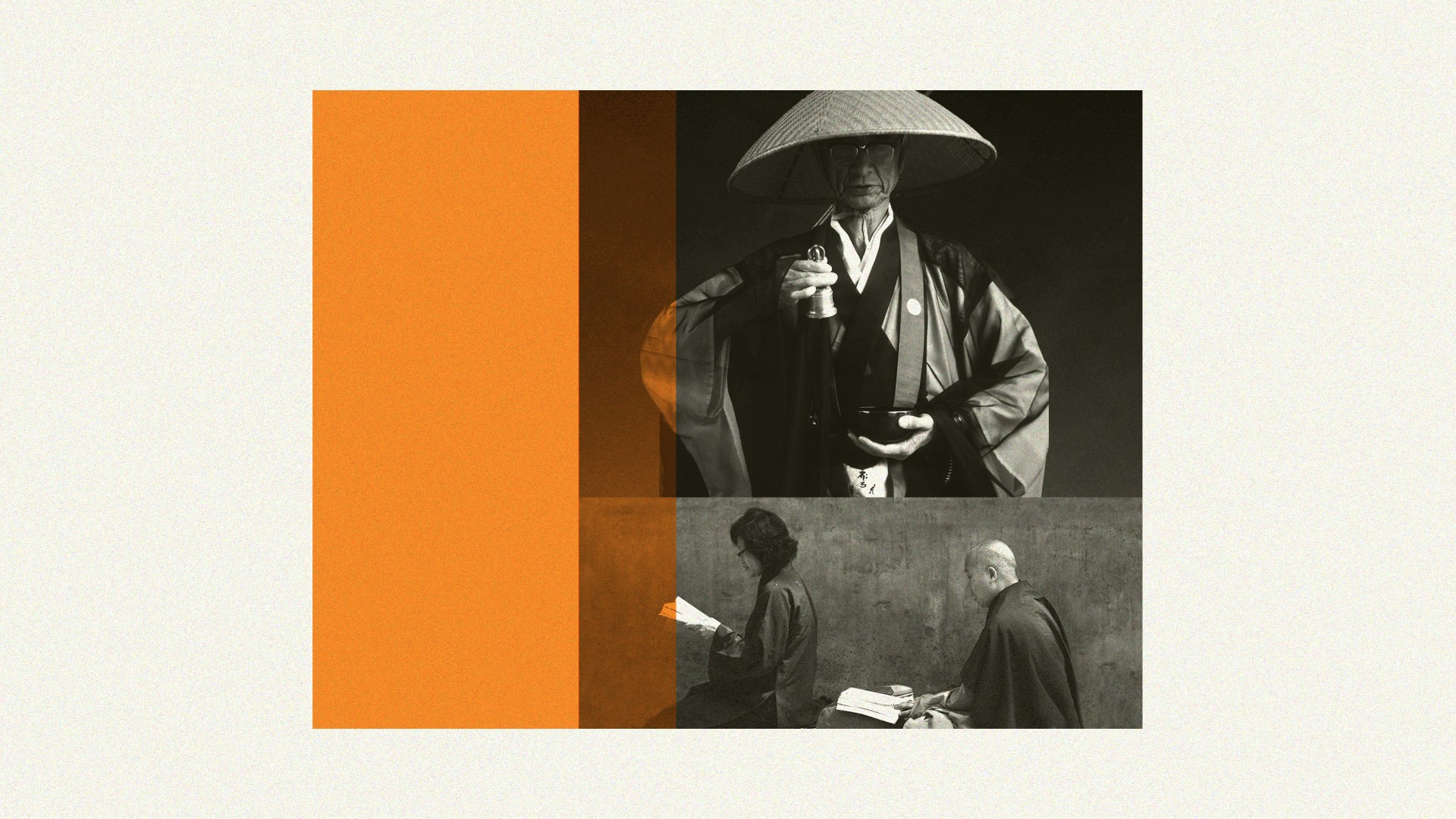

Theravada Buddhists like to point out Mahayana contradictions. In a karmic system, grace should play no part, and individual “merit” is all, so does it make sense to believe in bodhisattvas who can give great amounts of their accumulated merit to others who can then move up? Many Theravadas still try to achieve nirvana through ascetic self-effort based on monastic vows that both men and women can take. Ritual chanting and worship of relics may help in this process.

But Mahayana Buddhism has become more popular by developing a social orientation. Adherents should strive to have the capacity to become bodhisattvas, postponing entry into nirvana so they can help others by transferring their extra karmic merit to those they wish.

One popular Mahayana branch, called Pure Land (jodo in Japanese) tells the story of a monk who promised to create a Pure Land paradise in the West if he became a Buddha. Adherents of Jodo Shinshu say he succeeded, so in this Pure Land, evil does not exist. Those with faith in this Buddha get to go after death to the Pure Land, where conditions for liberation are excellent and the reincarnation process can be shortened. Mahayana is the dominant form of Buddhism in Japan and in many other countries, and the Pure Land approach is popular. Theravada Buddhism is dominant in Southeast Asia.

Some Buddhists repeat mantras that, when repeated thousands of times, will purportedly help the mind to overcome any surroundings. One school of thought teaches that constant invocation of the name Amitabha Buddha will transport the meditator to the Pure Land. A 17th-century Buddhist, Suzuki Shōsan, adapted Buddhism to the business world by instructing a merchant to “throw yourself headlong into worldly activity. …Your activity is an ascetic exercise that will cleanse you of all impurities. Challenge your mind and body by crossing mountain ranges. Purify your heart by fording rivers.”

Indicative of Buddhism’s diversity is the way Suzuki, often called the founding thinker of Japanese capitalism, developed a prosperity gospel: “If you understand that this life is but a trip through an evanescent world, and if you cast aside all attachments and desires and work hard, Heaven will protect you, the gods will bestow their favor, and your profits will be exceptional.” Another priest praised merchants’ nonattachment: “They go out early in the morning and return late at night. They do not avoid the elements nor do they dislike hardship and misery. They cover their bodies with cotton clothing and fill their mouths with vegetable food. They do not dare to throw away a piece of thread or a scrap of paper.”

Is Buddhism a laid-back way of developing great work-life balance? One 17th-century book, Shimin Nichiyo, answered questions such as this one from an artisan: “I am busy every minute of the day in an effort to earn my livelihood. How can I become a Buddha?” The answer: “Do not neglect diligent activity morning and evening. Work hard at the family occupation. Do not gamble. Rather than take a lot, take a little.”

Many Americans on the cultural left have gravitated to Buddhism, particularly in its Zen variety, as an opponent of materialism. But some Mahayana believers view selling as spiritual. Bodhisattvas show nonattachment to nirvana by sacrificing their own welfare, so “the business of merchants and of artisans is the profiting of others. By profiting others they receive the right to profit themselves. … The spirit of profiting others is the bodhisattva spirit.”

For more about four major religions, please see Marvin Olasky’s The Religions Next Door: What we need to know about Judaism, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Islam—and what reporters are missing.