Sitting with a student distraught by religious war, a God-fearing academic lamented the chaos in Syria, the destruction of Iraq, and the existential tensions seemingly ever-present in the Holy Land.

“What a great fortune it would be if … every man on earth could be under one religion,” he said. “[Then] there would be no more rancor or ill will among men, who hate each other because of the contrariness of beliefs.”

The academic’s answer, unfortunately, underestimates the human capacity for conflict. Beyond the bloody geopolitics, Islam, Christianity, and Judaism have split into sects and factions, to the point of killing fellow believers who share the same text yet hold different beliefs.

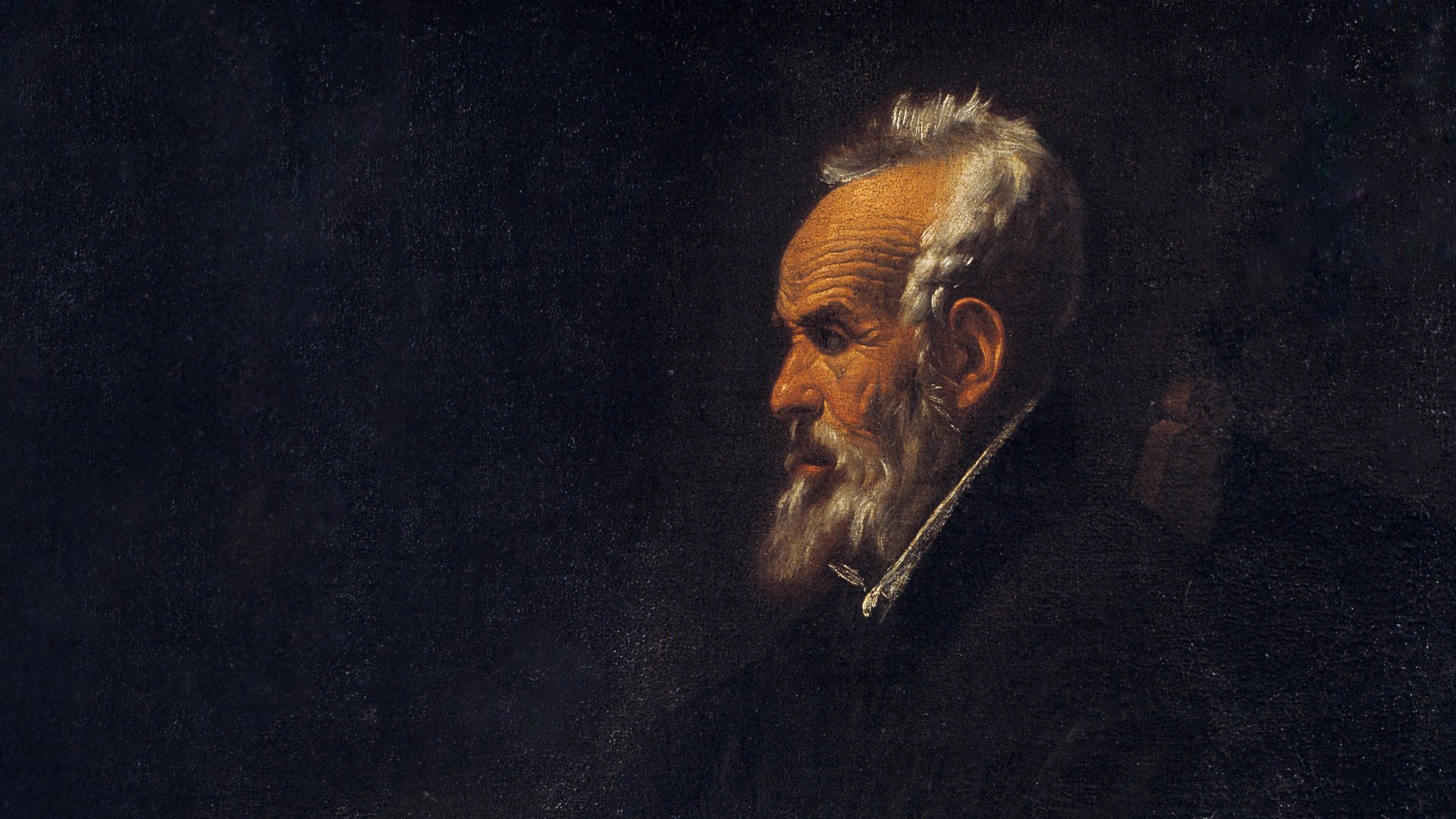

But for some, the “rancor and ill will” have prompted a corrective impulse to unite the faiths through interfaith dialogue. And the impulse is not new. The God-fearing academic? He’s a character from a book written in the 13th century by Ramon Llull, a Franciscan hermit and early proponent of an initiative still controversial among many believers today. Countercultural even then, The Book of the Gentile and the Three Wise Men addressed a world severely lacking in peaceful religious pluralism.

When Llull published his book in the 1270s, Crusaders were strengthening castles in Syria. The Mongol horde had sacked Muslim Baghdad—but then suffered defeat in Palestine, in the fields of Galilee. Llull wrote from what is now Spain, during the Reconquista, a military campaign to restore the Iberian Peninsula to Christendom. The Muslim realm, which they named Al-Andalus and became known as Andalucia, had been comparatively tolerant of Christians and Jews.

Llull lived on the island of Majorca, where his father settled after James I of Aragon declared victory in 1229. In the decades that followed, Christian kings in the liberated lands increased restrictions on non-Christian monotheists resident since the 8th century Islamic conquest. Some they forcibly converted, and within a few centuries, they expelled nearly all Muslims and Jews.

Llull, writing in Latin, Arabic, and his native Catalan, advocated for converting the non-Christians by rational argument, not the sword. While he did defend the Christian conquest of Muslim lands, he also founded missionary schools and traveled to North Africa, where he disputed with Islamic scholars.

Few of his contemporaries attempted the same. In fact, the literature concerning religion in the Middle Ages—across faiths—reflects a martial spirit that concludes with the authors’ faith triumphing decisively.

In the 12th century, for instance, Petrus Alfonsi published Dialogues Against the Jews, in which his imagined conversation partner converts to Christianity. Reversing the victor, Judah Halevi wrote The Kuzari: In Defense of the Despised Faith, in which a regional king embraces Judaism after hearing the cases of Islam and Christianity. A century later, Salih ibn al-Husayn al-Ghaffari made clear the Muslim case, composing The Shaming of Those Who Have Corrupted the Torah and the Gospel.

Llull operated differently. Though scholars maintain the book demonstrates a slight bias toward Christianity, he presents each of the three wise men’s discussion of their faith in straightforward terms. And when the philosopher chooses his religion in the end, the friends ask him not to reveal it. The book ends with the reader in ignorance, as the Muslim, Christian, and Jew desired to continue enjoying their conversation.

This conclusion might not sit well with Western evangelicals who may fear that the interfaith movement blurs the lines of doctrine and downplays the uniqueness of Jesus. Llull’s characters did not do so. Did the Christian lose an opportunity to encourage rival religious adherents toward the faith, some might ask, rather than just discussing belief?

Evangelicals in the Muslim world, however, might feel like the characters made a winsome decision to preserve peace and friendship in joint consideration of God. After all, since their community is usually less than a percentage point of the population, they must think about how to engage Islam peacefully.

Today, these realities have spurred some to partner with other Christians to create outposts for interfaith dialogue. They respect Muslims as citizens, neighbors, and fellow God-fearers—while holding to the Nicene Creed.

Last year, these pioneers and their Muslim counterparts met in Istanbul to launch the Network of Centers for Christian-Muslim Relations (NCCMR), a community of 18 entities stretching from Nigeria to Indonesia. In some countries, their religious communities are at odds. In others, people of different faiths for the most part live seamlessly among one another.

In our next piece, we will introduce Wageeh Mikhail, director of the NCCMR, and learn how his personal history of religious violence shaped his path to this work.