In this series

(Last of a series. For previous episodes, look here, here, and here.)

As religious historian Rodney Stark has shown, religions compete. Early in the seventh century AD, Judaism was making inroads in Arabia, but it had stringent entry requirements. While some Muslims early on were reluctant to accept new converts because they reduced the tax base (Muslims paid a lower rate), Islam increasingly welcomed everyone who simply declared, “There is no God but Allah, and Muhammad is his prophet.”

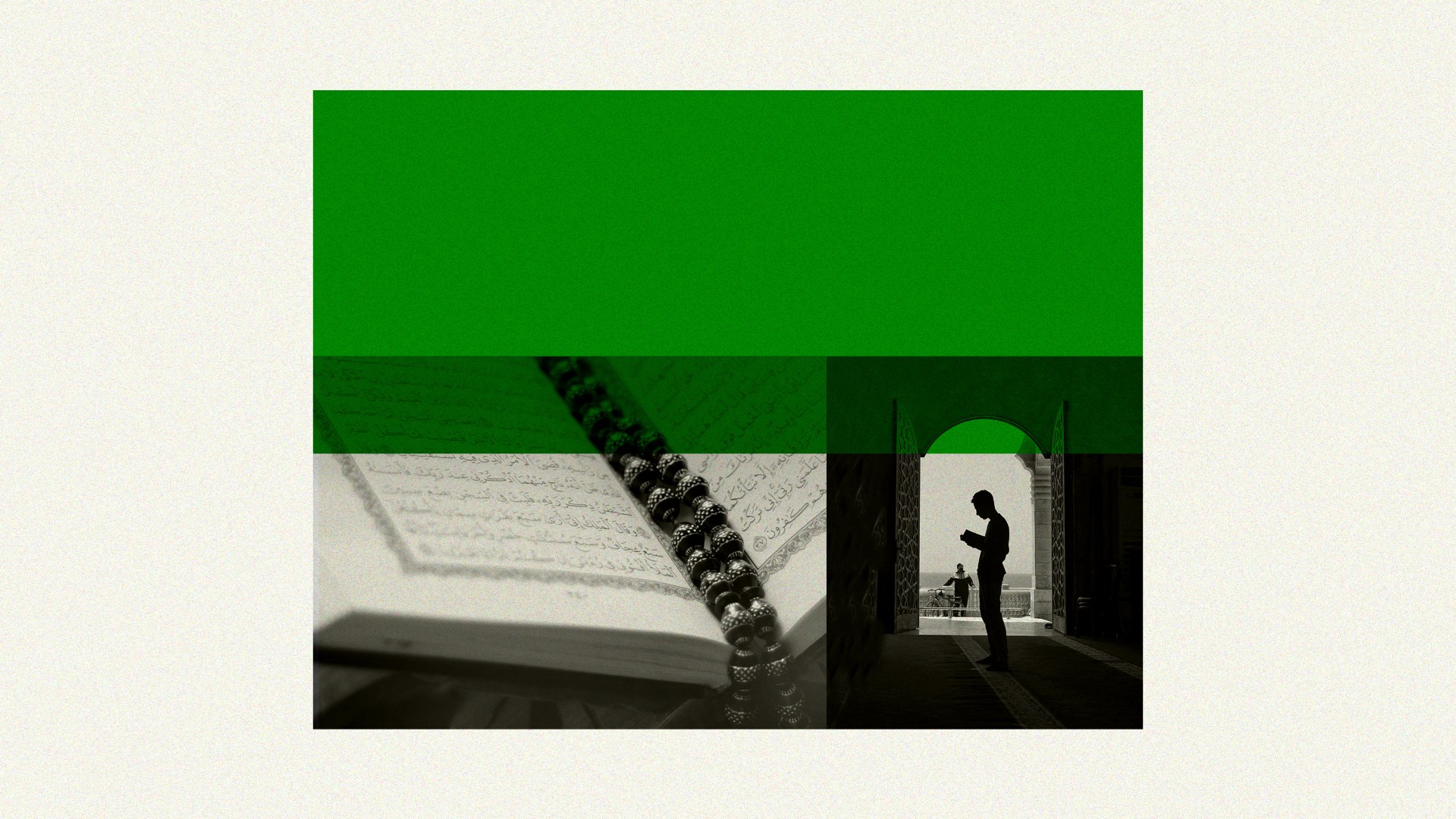

As is often the case in religions, a small number of commands proliferates into a vast array of injunctions. Islamic scholars have found within the Quran requirements about food (generally similar to those for Jews who keep kosher), rules concerning marriage and divorce, penalties for crimes, and commercial regulations including a ban on riba (usury).

Muslims are also to abstain from a variety of acts seen as harmful, including gambling. Islam bans consumption not only of drugs, seen as distorting thought, but also of alcohol, with no distinction between drinking a glass of wine and getting drunk.

Many rules are precise. For instance, do not eradicate insects by burning them because fire is to be used only on rats, scorpions, crows, kites, and mad dogs. However, some Iranians now push back against injunctions such as not reading the Quran in a house where there is a dog unless the dog is used for hunting, farming, or herding livestock. (A New York Times headline about Iranian law read, “Dog Walking Is a Clear Crime.”)

Some rules emphasize humility: Don’t boast about how you’ve contributed to build a mosque. Don’t set up elaborate grave markers. Don’t wear clothes just designed to attract attention.

Other rules restrict the activities of women. For example, women are supposed to go on hajj, but only with a husband or male relative. Men can practice polygamy in many Muslim traditions, and more than 25 percent of Muslims in six African countries, most notably Nigeria and Burkina Faso, live in polygamous households. (Some Christians in those countries do as well.) In general, more Muslim and Orthodox Jewish men than women attend services, with separate and usually smaller prayer spaces provided for females. Christianity is opposite.

Sociology is downstream from theology. Muslims say Muhammad received the revelation of the Quran from the angel Jibreel (Gabriel) in AD 610 and became a strong defender of the autonomy and uniqueness of Allah. He took on the task of moving his countrymen from polytheism and decadence to monotheism and morality, but they initially opposed him.

In AD 622, facing persecution in Mecca, Muhammad escaped 275 miles north to Yathrib, an oasis village later renamed Medina, the city of the prophet. (Muslims today follow a lunar calendar that starts with this trip, called the Hijrah.) Jews in Medina antagonized him by rejecting his message, but Muhammad defeated opponents and unified nomadic Arab tribes before his death in 632.

Believing Muslims say we should have faith in the Quran because Allah literally spoke it to the angel Jibreel, who in turn gave it directly to Muhammad over a 23-year period from the time Muhammad was 40 years old. They say that Muhammad told associates what Jibreel had said and that they memorized his words.

Since Muslims portray Muhammad as sinless, they are to ask themselves every day WWMD: “What would Muhammad do?” Believers try to sleep, eat, drink, and even dress as he did. They try to repeat the special prayers he uttered upon going to sleep and waking up, or even upon entering and leaving the bathroom.

Many also say the Quran praises the extension of Islam through military might: “Surely Allah loves those who fight in His cause in solid ranks as if they were one concrete structure” (Sura 61:4). The Quran condemns those who hang back: “What is the matter with you that when you are asked to march forth in the cause of Allah, you cling firmly to your land? Do you prefer the life of this world over the Hereafter? The enjoyment of this worldly life is insignificant compared to that of the Hereafter. If you do not march forth, He will afflict you with a painful torment and replace you with other people” (9:38–39).

Some Muslims use those verses to commend militant expansion of Islam. Christianity has the Crusades on its permanent record; however, many avoid using the word crusade now. Campus Crusade for Christ changed its name to Cru, and the Christian Anti-Communism Crusade is now past tense. Jesus said, “Give back to Caesar what is Caesar’s” (Matt. 22:21), but Muhammad was a theological, political, and military leader rolled into one.

Unlike Christians who eventually separated church and state, Muslims in the modern era have struggled to define the role of each sphere. The Quran teaches, “Let there be no compulsion in religion” (Sura 2:256), yet the role of government is to enforce the law. Islam permits freedom of worship for Jews and Christians, but not the propagation of their creed.

An oft-cited but disputed tradition from Muhammad says those who leave Islam must be killed. Several Muslim countries have anti-blasphemy laws that include capital punishment, although the level of enforcement varies. Still, cultural rejection that can even include honor killing is one reason fewer people publicly disaffiliate from Islam than from Christianity.

While living in Washington, DC, from 1989 to 1991, I joined a PCA church pastored by scholar Palmer Robertson, who provided a Bible reading plan for most readers and one with about triple the amount “for the hearty ones.” In that tradition, I recommend, at the close of this series, a just-published book by John Tolan, Islam: A New History from Muhammad to the Present (Princeton, 2025).

Regarding the early expansion of Islam, Tolan writes, “The Arabic texts that chronicle these conquests portray them as an acting out of God’s will… through the valorous exploits of Muslim armies.” Religion-based autocracy is also a fact of recent years, as Tolan concludes: “It would take many pages to mention all the heads of state, from Morocco to Indonesia, who mobilized Islam to legitimize their power in the face of their subjects or citizens, or who manipulated various currents of Islam to try to find allies.”

But Tolan also highlights peaceful aspects of Islam, starting with his cover portrait of Rabia al-Adawiyya, a mystic poetess and flute player who lived in what is now Iraq and helped to found Sufism. By official affiliation, it’s a small stream compared to Islam’s Tigris and Euphrates (the Sunni and Shiite sects) but one indication of the religion’s complexity.