This piece was adapted from Russell Moore’s newsletter. Subscribe here. Want to listen instead? Russell Moore reads the piece aloud on his podcast.

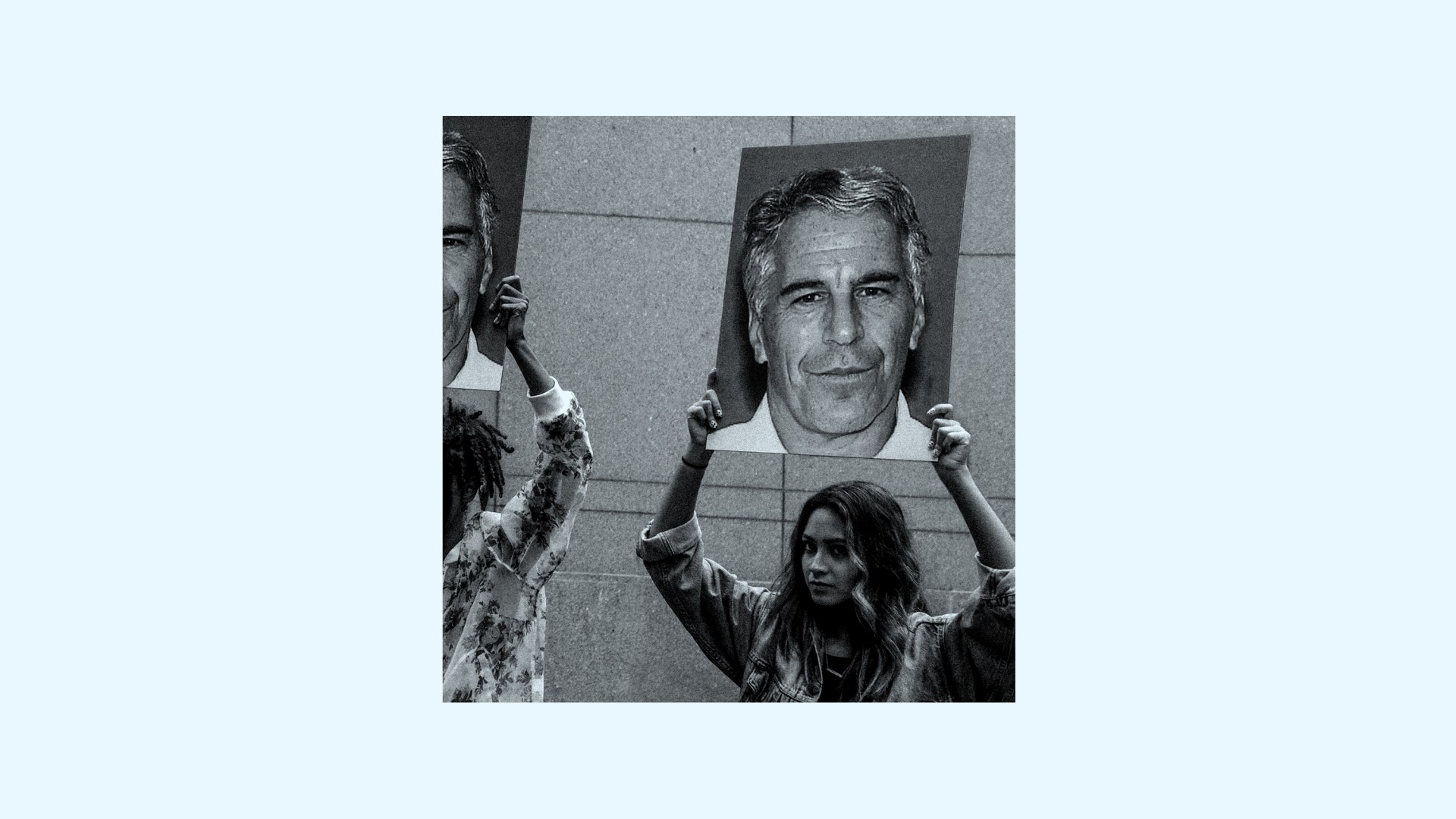

Sometime last winter, I was jarred by a picture on social media of a Christmas ornament: a figure of a smiling Jeffrey Epstein attached to the tree by a noose around his neck. The caption on the post read: “This ornament didn’t hang itself.”

The reference to the popular notion that the alleged sex trafficker’s suicide in prison was perhaps murder didn’t strike me as resonant with holiday cheer. I couldn’t have imagined that, come summer, Epstein would be the most inflammatory conversation topic in the country.

The controversy was ignited by Attorney General Pam Bondi’s refusal to release the files from the Epstein case, including the “client list” of those involved in Epstein’s ring of powerful friends alleged to have assaulted multiple girls and young women.

At first, the attorney general said the files were on her desk and she would release them later. Then she said there were no such files, just Epstein’s own videos of abuse. Then President Donald Trump implied that there were files but that they had been faked by some of his political opponents who somehow had access to the levers of justice long after they left office.

The president then told people to stop talking about Epstein. But people have not stopped talking about Epstein. Those enraged by all this include some of Trump’s most enthusiastic backers—Tucker Carlson, Laura Ingraham, Glenn Beck, Alex Jones, and, of course, Elon Musk, who suggested on his social media platform several weeks ago that the files are not released because Trump is named in them.

To see why this moment matters, we might look backward to another time. Before Richard Nixon went to China, he went to Disney World. There at the Orlando resort, in the fall of 1973, the president told newspaper journalists that he welcomed questions about the Watergate scandal because “people have got to know whether or not their president is a crook.” His next statement defined an era: “Well, I’m not a crook.”

If you made it through your high school American history class, you know that Nixon did not, in fact, welcome questions into Watergate. And you know that—whatever else one might think of Nixon—the “I’m not a crook” statement was answered on tape, in Nixon’s own words. The American people heard what came to be known as the “smoking gun” recording, in which the whole country heard Nixon ordering what he said he never did. Some felt betrayed. Some felt vindicated. The country decided to move on.

I’m not sure that “Stop talking about Epstein” will be taught to high schoolers in 2065 in the same way that “I’m not a crook” is. We are unlikely to ever see the files. We are also likely to be in the middle of another all-consuming national conversation in a matter of days, maybe even by the time you are reading this.

Even so, we should ask ourselves what this moment means. Why do we want to see the Epstein files?

The most obvious reason is that we want justice done. We want to believe that our institutions—even in the present crises of credibility that most are going through—are not wholly corrupt. Most people don’t want the kind of country in which a poor person is behind bars for drug possession while some of the wealthiest and most powerful men in the world rape women on a Caribbean island with no penalty whatsoever.

This impulse is a good one. In fact, it is more than just a moral instinct. It is written on the heart. “You shall do no injustice in court,” God said through Moses. “You shall not be partial to the poor or defer to the great, but in righteousness shall you judge your neighbor” (Lev. 19:15, ESV throughout). That principle is repeated in various ways throughout both the Old and New Testaments.

Behind this moral foundation, though, there might be something else more specific to this moment in American history. The Epstein files might be a parable, a stand-in for a definitive settling of what has ripped America apart: a way to see, in real time and without dispute, who are the good guys and who are the bad guys.

The pro-Trump media ecosystem spent years talking about the files and the fishy circumstances around Epstein’s death because it was part of a larger story: about how Trump was standing up to a “deep state” cabal that was, among other things, trafficking children. For these people, the Epstein files were meant to show that, like the Hunter Biden laptop, there really was a story there that the people they mistrust didn’t want to talk about.

Those of us who don’t support the president, on the other hand, are no less pulled toward the story of a conclusion to the moral divide of this time. The Epstein files suppressed by a president who was friends with the dead villain would finally cause our neighbors and friends to walk away from the kind of character that’s been celebrated over the last decade.

But that’s not going to happen—no matter what happens with the Epstein files. The revelation that Nixon had lied about Watergate wasn’t a shocking reversal of image to the degree that it would have been if, for instance, Mother Teresa had been discovered to have a private jet or if Gerald Ford had been seen coming out of a strip club. For years, Nixon had carried the nickname “Tricky Dick.” Still, many of his supporters were stunned when Nixon—as songwriter Merle Haggard put it—“lied to us all on TV.”

I’m not sure we are in an era where a shared morality would trump tribal identity. After all, we all heard the Access Hollywood recordings. We all saw January 6. None of these things ultimately mattered, if by “mattered” we mean resolved the political divide. But they will matter in history. Those who come after us will be horrified that our generation looked away from these matters of character—or they will approve of such things as good.

With the Epstein files, part of what we want is—at long last—unity, agreement that there is something on which we, as a matter of moral principle, can agree is wrong. We also want justice: the right prosecution of those who have ruined lives. I doubt we will get either, but it’s possible.

Behind all that, however, we want something even bigger. We cry out for wrongs to be righted and evil to be avenged in a more ultimate sense than any Department of Justice can grant. Regardless of what happens here, for that, we will have to wait.

We should pursue justice as far as we can while recognizing that even when it is not done, no one will get away with it. Jesus said, “So have no fear of them, for nothing is covered that will not be revealed, or hidden that will not be known” (Matt. 10:26).

Whoever the victims are, they will be heard. Whoever those who harmed them are, they will be found out. The Epstein files may never be opened on earth, but do not be deceived; they are open in heaven.

Russell Moore is the editor in chief at Christianity Today and leads its Public Theology Project.