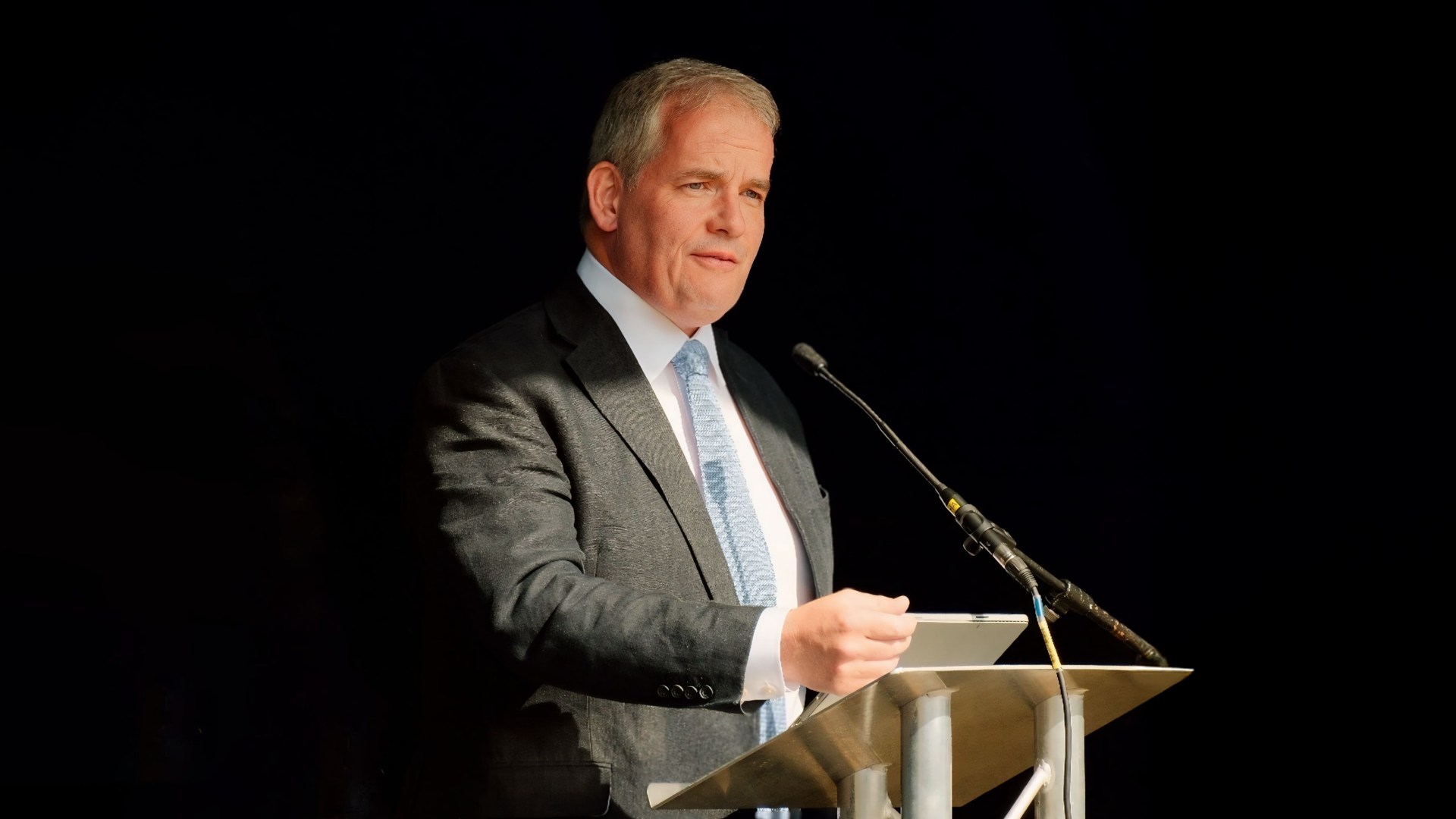

On Colin Bloom’s first day as head of Barnabas Aid International in April 2024, he gathered his team together and gave them a simple message.

“We as an organization have done wrong,” he said. “We have to own our mistakes and corporately repent.”

Not the typical first-day pep talk from a new CEO. But then nothing is normal these days at Barnabas Aid, the evangelical, UK-based charity that serves the persecuted church.

Bloom, a former Conservative Party politician with a background in business, recently described it like this: Imagine you’re in the cockpit of a crippled Boeing 747. The plane is going down. It’s plunging into the side of a mountain. You have to somehow fix the plane so it can keep flying, and you have to fix it in midair.

And one more thing, Bloom said with a grim smile: “The previous captain is still trying to kick the door in.”

Even in an era rocked by scandals, the scandal of Barnabas Aid has proved especially tumultuous. Many British evangelicals still ask themselves, What happened? Now they are also asking another question: Can one part of this ministry recover? Will some tough leadership, clear commitment to doing the right thing, honesty, and transparency be enough to repair the damage?

Not everyone is convinced, but it’s starting to look like the answer might be yes.

Bloom is at the head of Barnabas Aid because the board of trustees forced out founder Patrick Sookhdeo and three top officials in 2024.

Sookhdeo, a Christian convert from Islam, founded Barnabas Aid in 1993 and named the organization after Barnabas from the Book of Acts, whose name means “son of encouragement.” The ministry quickly grew into one of the largest organizations in the world serving the persecuted church, with annual spending in the tens of millions of dollars.

Today, it is a family of international charities with branches in the United States, Australia, South Africa, and beyond. Sookhdeo came to be recognized as an evangelical leader in Great Britain and also achieved some fame as a critic of Islam.

Then, in 2014, he was arrested. A member of Sookhdeo’s staff accused him of calling her into his office and touching her inappropriately. The charity quickly closed ranks. There was a cursory internal investigation, and Sookhdeo was exonerated. Barnabas Aid said the accusations were not only untrue but also malicious—an outrageous attempt to destroy Sookhdeo and the ministry.

Mark Woods, a Baptist minister and journalist who investigated Sookhdeo, said Barnabas Aid leaders were quick to deploy the “textbook” defense of any Christian leader caught in wrongdoing. They said his critics were just hostile to the work he was doing and, ultimately, to the gospel itself.

“He was on the side of the angels,” Woods said. “To lose faith in him was, in a sense, to lose faith in the cause.”

The argument was persuasive to many of Barnabas Aid’s faithful donors, who believed passionately in the importance of helping the persecuted church.

The British legal system was not so easy to manipulate. Sookhdeo was put on trial and convicted of sexual assault and two further charges of intimidating witnesses after he was caught pressuring Barnabas Aid staff not to cooperate with the police. The court sentenced him to community service.

Around the same time, someone inside Barnabas Aid leaked financial records to the media. They showed lax financial controls—in some places nonexistent. Barnabas funds were going to a network of interconnected charities, all controlled by Sookhdeo and close associates.

There were more assault charges in 2015, with allegations he had touched a woman inappropriately in 1977. Barnabas Aid trustees sprang to his defense, publishing a 36-page document defending the founder and attacking his accuser and a handful of major evangelical organizations in Great Britain. Sookhdeo was the real victim, they claimed, suffering “sustained attacks” and “destructive opposition, seemingly aimed at breaking individuals and crippling organizations.”

In 2018, a jury concluded there was not enough evidence to convict Sookhdeo of a 41-year-old crime. By then many evangelical leaders had distanced themselves from Barnabas Aid.

Sookhdeo did not respond to CT’s request for comment on this story.

Despite the many scandals, Sookhdeo still has many staunch evangelical supporters. Christian leaders who work in international missions told CT they have been appalled at how hard it has been to convince people in the pews not to believe what Sookhdeo says.

Jos Strengholt, a Dutch missionary who works in Egypt and was once a major recipient of Barnabas funds, said many faithful British Christians just swallow Sookhdeo’s stories whole. Strengholt came to see Sookhdeo as a charismatic fabulist who would tell any story to create the reality he wanted. He cultivated a sense that Christians were under siege, Strengholt said, and people believed every overblown persecution narrative.

Many evangelical donors only found out something was amiss inside Barnabas Aid when they started to get contradictory emails. A group of staffers started revolting against Sookhdeo’s leadership and filed more than 100 whistleblower complaints about mismanagement and financial misconduct with the board in April last year.

The whistleblowers claimed that Sookhdeo was an authoritarian who brooked no dissent and made financial decisions on a whim, Bloom told CT.

“There was no rigor,” Bloom said. “It was like a Roman emperor—thumbs up or thumbs down.”

Staff claimed the ministry was pervaded by a culture of fear and anyone who spoke out was punished. Retribution was swift and brutal.

The board took action, suspending Sookhdeo and his top allies and bringing in a law firm to investigate. The report came back a few months later. Investigators said Barnabas Aid was a “toxic work environment” and they found “serious and repeated contraventions of internal policies.”

They also found fraud: The report said Noel Frost, the head of international operations, had siphoned £130,000 (about $176,000) into his bank accounts. The Barnabas Aid board reported the allegations to authorities, and soon police and the British charity regulators were doing their own investigation.

Authorities put strict controls in place while investigating Barnabas Aid for fraud. The organization is not allowed to spend more than £4,000 (about $5,400) without government approval. The investigation is ongoing, and authorities declined to comment for this article.

The board replaced Sookhdeo with Bloom, and one of Bloom’s first jobs was to email the financial supporters of the ministry and explain what was happening. But just as he did, donors also started receiving messages from Sookhdeo claiming he was the victim of a coup. Working under the auspices of a subsidiary charity, Sookhdeo also said he was still in charge of the real Barnabas Aid, even though the international board had ousted him.

“It was chaotic,” Bloom said.

Bloom told CT he expected some “rough-and-tumble” when he accepted the job of leading Barnabas Aid. But the vituperative attacks still surprised him. He has been smeared online, and he said Sookhdeo’s supporters have also showed up at his home and photographed his family.

Longtime donors heard rumors that Bloom was ushering in New Age practices at Barnabas Aid. He previously served as the Conservative Party’s senior faith adviser, and before that he ran a network of Christian care homes, but panicked donors believed Bloom was dropping the charity’s commitment to Christian belief.

It wasn’t true, Bloom said.

“Utter codswallop,” he told CT. “Everyone we have recruited is a Bible-believing follower of Jesus who can sign … our statement of faith.”

One option, in the midst of the conflict and ongoing tumult, might have been to shut the ministry down. Bloom was resolute that Barnabas Aid had a future.

“The correct thing to do is to own our mistakes and be transparent,” he said.

He believed there was still a need for the work Barnabas Aid was doing, especially when the ministry gave funds directly to Christians facing oppression. Barnabas Aid still has deep pockets and lots of goodwill, and Bloom said he believes that if they can repair the plane in midair, the ministry will become an example of second chances, encouraging Christians around the world.

“If we do the right thing,” he said, “then the Lord will honor that and will bless us as we try to bless others.”

A big part of that effort, for the new CEO, involves rebuilding trust and demonstrating continued commitment to the mission combined with a new commitment to transparency. Today, every penny is accounted for, according to Bloom, and he holds regular town-hall-style meetings with donors to show them where all the money is going.

He tells them how the staff is now making spending decisions based on evidence and data, not the whims of the founder. Team leaders who used to just get told what Sookhdeo wanted them to do now travel overseas themselves to assess local projects and help make decisions.

The charity is sending more funds than ever to the persecuted church, even with the ongoing regulation requiring all expenditures over £4,000 get preapproved. While spending remains high, donations have fallen as donors learned about the chaos. Bloom said this is why he was working so hard to reassure supporters it is safe to resume giving.

Objections and counterarguments about the “real” Barnabas Aid have died down a bit since November, when Sookhdeo and his top deputy were arrested on charges of fraud and money laundering.

Bloom said he’s also made sure the staff overseeing the finances are all properly qualified, and he’s installed a vigilant human resources team. Staff members told CT the changes from Sookhdeo’s leadership to Bloom’s are “night and day” and they are excited about the ways the ministry is becoming more effective.

The longtime Barnabas Aid staffers have been through a lot, but Bloom encourages them to focus on the people they’re helping. This spring, during the 15-minute staff Bible study, he talked about the body of Christ and how Paul said, “If one part suffers, every part suffers with it” (1 Cor. 12:26). The same verse is printed on a poster in Bloom’s office beneath a striking image of one of the persecuted Christians supported by the charity.

“Her life is a thousand times worse than everyone in this office,” Bloom said.

The mission remains urgent. That hasn’t changed.

“What has changed,” Bloom told CT, “is our resolute commitment to acting with integrity.”

Will it be enough? It is hard to tell.

The journalist Mark Woods, for one, is skeptical that a good CEO will be able to repair the charity and pick up the pieces that Sookhdeo left behind.

“I don’t use this sort of language lightly, but there is a quality of evil about the way [Sookhdeo] behaved and the damage that he has done,” Woods said. But “if anyone can save Barnabas, it will be somebody like Colin Bloom, who is a very experienced and very tough-minded Christian leader.”