When Doechii’s song “Anxiety” went viral at the beginning of the summer, thousands of social media users participated in the dance trend, posting videos of themselves shimmying back and forth to the lyrics “Somebody’s watching me, it’s my anxiety.”

Then, Christian content creators jumped on the “Anxiety” bandwagon—to rebuke the song. Some warned that “anxiety is a demonic spirit”; others posted musical rebuttals. One creator posted a video in which he claimed that the song is “demonic” and gave him sleep paralysis.

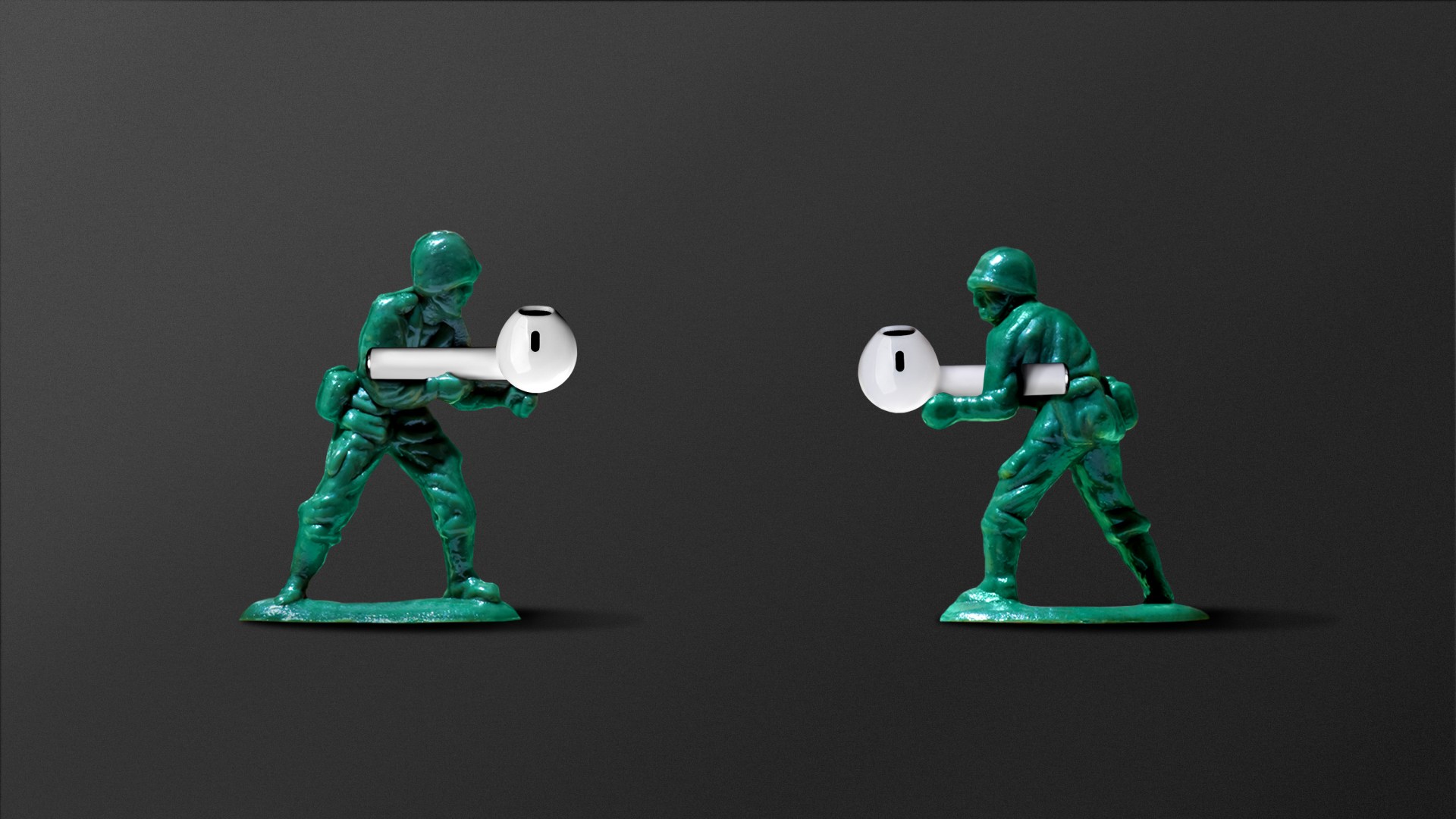

Their claims resemble warnings about 1980s and ’90s rock music from fundamentalists like Bill Gothard and Jim Logan. But the new wave of Satanic Panic over popular music doesn’t stem from fiery preachers in suits—this time, it’s Christian influencers and musicians stoking alarm.

Meanwhile, popular worship music from charismatic outlets like Bethel Church has recentered power and spiritual warfare. The theology, in turn, escalates fears about what music can do, or rather, what music can be used to do: Christians who view their worship as a weapon become more likely to see music as a weapon that can be used against them.

Music affects human hearts and minds. But is it a weapon that evil forces use against listeners?

Bethel holds to a “theology of encounter and presence” and sees musical worship as “a means to carry out revival in our world,” according to Emily Snider Andrews, executive director of the Center for Worship and the Arts at Samford University. Andrews said that, in Bethel’s framework, musical worship is an “infiltrating” force for Christians to “invade society” and build “kingdom culture.”

The lyrics of the song “Revival’s in the Air,” for example, speak of coming culture change (“Revival’s in the air; / Catch it if you can” and “The dawn is breaking”). And the song “We Make Space” invites God to “invade, take over this space” and “surround, engulf.”

These ideas and beliefs extend beyond Bethel. Popular worship leader and songwriter Rita Springer hosts a podcast called “Worship is My Weapon.” The song “Sevens” on Brandon Lake’s new hit album calls listeners repeatedly to “ready the weapon of praise.”

Todd Korpi, dean of digital ministry at Ascent College, said that beliefs about the power of musical worship vary in “Spirit-filled” traditions. But in general, he said, Christians in charismatic or Pentecostal communities share the belief that “when we sing together, we come into alignment with one another” and that there is real power in that “all-encompassing unity.”

Former Bethel worship leader Sean Feucht is a prominent example of an artist who explicitly frames worship as culture war. Most Bethel collaborators aren’t as combative but still believe in the power of musical worship. And beliefs about its wonder-working power—like the ability to manifest literal “glory clouds” of gold dust above a singing congregation—are common.

In addition to encountering a theology of worship that treats praise as power, a generation of young Christians and spiritual seekers are finding a chorus of online voices theorizing about the spiritual power of music and warning about its dangers.

Recently, Christian rapper Hulvey told podcaster George Janko that his “spirit will feel disturbed” when listening to some secular hip-hop music. Author and hip-hop artist Jackie Hill Perry has speculated that some secular music succeeds because the producers have help from demons.

Theatrical preachers are performing mass exorcisms and reanimating conversations about spiritual warfare and demonic possession. Some Christian influencers declare that “secular concerts are demonic rituals,” and others post that, the closer they get to God, the more unbearable secular music becomes to listen to.

The popular podcast Girls Gone Bible recently featured a guest who suggested that Satan is musical in nature and that demons can “sing through” musicians when they are drunk or high.

“If you know anything about the spiritual realm you know large artists like [Taylor Swift] are operating in darkness,” one influencer posted on Instagram, talking about why she doesn’t let her daughters listen to Swift’s music. Instead, she says, she “blasts [Forrest] Frank.”

Now, as Christian music’s popularity is growing, some artists and influencers are seizing the moment to reassert the niche as a spiritually safe and nourishing space in an otherwise dark entertainment industry.

Christian musicians claim that they are making music using God’s tuning, suggesting that sonic frequencies can positively or negatively affect bodies and minds. Other artists post that audiences can replace “toxic” secular music with their faith-based songs.

Charismatic Christians have historically read biblical narratives about music—such as the story of David playing the harp to soothe King Saul in 1 Samuel 16:23—as evidence that there is something particularly powerful about the medium.

“We have passages describing Paul and Silas singing in prison or Miriam and the women singing in Exodus,” said Tim Larsen, professor of theology at Wheaton College. “Charismatics will read these as saying that there is a spiritual efficaciousness to praise. And there seems to be a strong connection between music and the prophetic.”

Larsen suggests that music is one of many channels for the spiritual that Christians can point to in Scripture, but that superstition arises when believers start to see the vehicle itself as having special power.

But not all charismatic Christians see music the same way. In the Vineyard movement, a neo-charismatic association that grew out of Calvary Chapel in Costa Mesa, California, worship leaders tend to emphasize music as a channel for individual intimacy with God rather than a vehicle for collective empowerment or breakthrough.

“In practice, music has a sacramental quality in that it can be filled by the real presence of God,” said Caleb Maskell, associate national director of theology and education for Vineyard USA. He added that the sacramental understanding of music doesn’t stem from belief in the mystical power of music. “In reality, it’s the people who are filled with the presence of God.”

Adam Russell, director of Vineyard Worship USA, said that over the past 20 years, he has seen a movement in contemporary worship music away from intimacy and toward “intensity.”

“My Pentecostal brothers and sisters have a really strong sense that when we worship, we’re doing something apostolic or bringing the kingdom,” said Russell. “But in Vineyard, we’re not about bringing the kingdom; we’re discovering the kingdom. It’s already been sown. We’re not here to enforce it upon culture.”

Maskell and Russell contrast Vineyard’s view of the power of musical worship with the theology articulated in lyrics about praise as a weapon or the act of worship as warfare. According to Russell, Vineyard has been criticized in the past for producing sentimental “love songs to Jesus,” but that emotional earnestness without a battle mentality is what sets it apart and keeps music in its proper place theologically.

“Some people might say that Vineyard songs are a little sappy,” said Russell, “and maybe so. But that’s been our superpower: to sing directly to Jesus, from the heart.”

Examples of less “sappy” and more militant songs are easy to find these days, including at least three ranking among the top 100 sung in churches. Bethel Music’s “Raise a Hallelujah” includes the lyrics “My weapon is a melody” and “Heaven comes to fight for me.” It’s an anthem about singing “hallelujah” in the presence of the Enemy to drive out darkness.

Elevation Worship’s hit song “Praise” features the lines “Praise is the water / My enemies drown in” and “My praise is my weapon. / It’s more than a sound. / My praise is the shout / That brings Jericho down.” Similarly, the chorus of Phil Wickham’s “Battle Belongs” frames prayer and worship as a fight (“When I fight, I’ll fight on my knees / With my hands lifted high”).

In Vineyard churches and at Bethel, encounter with the divine is a goal of congregational singing. Vineyard emphasizes intimacy and introspection; Bethel emphasizes inbreaking and victory. The latter tends to grant more agency to the act of singing, but worshipers in both circles believe that musical worship does something.

Maskell said musical worship that tries to summon God to act is misguided. “Worship as intercession is about drawing close to the presence of God in my own life and relationships, not ‘God, do things to other people,’” he said.

But scholars see a fine line between keeping music in its proper place theologically and dismissing its potential to be an agent of spiritual formation.

Korpi said that charismatic Christians generally take seriously the “formative power” of media, including film, music, and literature. There is a difference between avoiding, for one’s peace of mind, lyrics or images that depict immorality and attributing invasive, corrupting influence to them.

Panic about the potential dangers of certain kinds of music is rooted in the belief that if Christians can mobilize music as a weapon of spiritual warfare, music can also be used against them. Preachers and politicians who railed against hidden messages in rock or heavy metal during the ’80s stoked fear that music could invade listeners against their will, opening a door for evil into the mind or soul.

Christians who see musical worship as ammunition in a spiritual war are primed to see music as a tool of their enemies. And when it’s easier than ever to access an endless stream of music to accompany daily life, Christians understandably want to understand its potential impacts on their emotional and spiritual well-being.

But the view that music can serve as a hidden inroad for spiritual oppression or the demonic is one that sows fear, said Larsen, cautioning that this kind of “magical thinking” verges on gnosticism. “Gnosticism promises hidden knowledge. Discipleship is about obvious, simple knowledge,” said Larsen. “Paul says, ‘Eat what you want and give thanks to God, and trust that he will protect you.’”