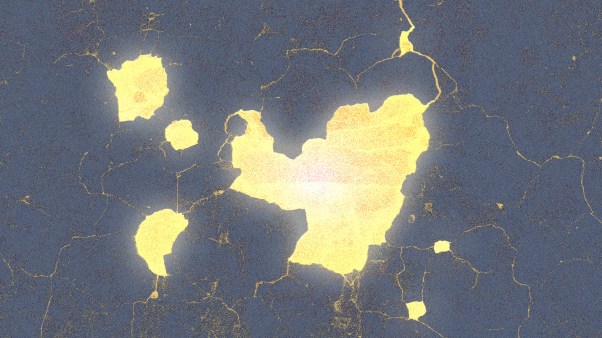

When Hadi Maao was five years old, his mud-brick home collapsed on him after Muslim extremists detonated car bombs in his northern Iraqi village. Seven years later, in 2014, ISIS jihadists forced his community in the district of Sinjar to flee to the mountains. Now 22, he is an asylum seeker in the Netherlands and sends a quarter of his meager earnings as a grocery shelf stocker to his family still sheltering in a United Nations camp for internally displaced Yazidis.

“Sinjar is not a place to live,” he said. “I’m afraid people are forgetting us.”

US Agency for International Development (USAID) cuts have made things worse, pausing the reconstruction of Yazidi villages and overwhelming medical centers. An evangelical organization is trying to fill the gap, while a new generation of Yazidis living abroad are seeking ways to help. In this three-part series, we will also cover the complications of Christian aid in Sinjar and explain the basics of the Yazidi religion that Maao and his people follow.

Maao is the youngest of four brothers and three sisters. All of his siblings currently live in Sardashti Camp in the Nineveh Valley, 12 miles east of the Syrian border. The money Maao sends home contributes to building a concrete house for his aging mother and father. They currently reside with his cousin’s family in the UN’s standard canvas tent.

At the International Religious Freedom Summit in February, Vice President JD Vance praised the first Trump administration’s action to bring aid to Yazidis and Christians “facing genocidal terror from ISIS.” Yet President Donald Trump’s executive order to freeze foreign funding and the subsequent dismantling of USAID has had a disastrous effect on the camps where Yazidis still live.

The camp is full of tattered tents that allow rain leakage, unhygienic bathroom facilities, and the threat of fire from spark-prone electricity cables, according to on-the-ground sources that CT spoke with. Cuts have halted the building of schools, community centers, and water purification units. An unused transformer, delivered prior to the stop-work order, was placed in storage.

Maao is from the village of Tel Ezer, also known as al-Qahtaniyah, where USAID sponsored one of five nascent youth centers. In the wake of ISIS attacks, the agency created a women’s media platform and sponsored a display of 300 cultural artifacts to showcase the region’s shared Yezidi, Muslim, and Christian heritage. USAID also contributed to building a cemetery in the village of Kocho, in addition to homes for families of 130 victims of ISIS. At least 150,000 were able to leave the camps and returned home.

Since 2003, Iraq received $9.3 billion in USAID assistance, which helped sustain 15,000 small businesses and provided vocational training to 75,000 Iraqis. In Sinjar, 30,000 Yazidis gained access to essential services, including medical clinics in more than a dozen Yazidi camps. One source, speaking on background, said they are now operating at 25 percent capacity. Iraqi government contributions maintain some staff presence, but patient cases rapidly exhaust preexisting supplies without adequate replacement. Authorities are encouraging Yazidis to travel to state facilities, but many are reluctant to return to Muslim areas given the memory of ISIS.

“Our wounds are not yet healed,” Maao said. “Our women have not returned, and the bones of our martyrs are still scattered across our ancient homeland.”

Yazidis are an ancient people whose faith has roots in ancient Mesopotamian and Zoroastrian religion. Aspects resemble Christianity and Islam, but ISIS followed medieval fatwas declaring that the community should be subject to death.

As ISIS expanded its self-proclaimed caliphate in 2014, the extremists drove tens of thousands of Yazidis to take refuge in the mountains. Maao described living in a cave for more than a week in 120-degree weather with little food or water. His father braved a return to a nearby village to get supplies. Another survivor, Hussein Salem, told CT he remembers bullets flying over his head and the lack of medication as his mother fell ill.

Only the airdrops and military support from a US-led coalition preserved their survival.

Maao’s family attempted to return to Tel Ezer in 2021 but did not feel safe. ISIS killed more than 1,200 Yazidis, kidnapped children to serve as soldiers, and enslaved more than 6,000 women in forced marriage and concubinage. One count estimates that 2,500 members of the community are still missing.

Sources said that since the defeat of ISIS, many large international organizations like Doctors Without Borders, World Vision, and Medair provided extensive aid to the Yazidi community. But as world crises multiplied in Ukraine and elsewhere, many aid groups have ceased operations. Smaller groups remain in the camps, many of which are evangelical.

Ashty Bahro, an Iraqi believer of Chaldean Catholic background, runs Zalal Life from Duhok in the Kurdistan region, serving three Yazidi camps and dozens of villages. Beneficiaries of the group’s food distribution, vocational training, and medical services also include area Christians and Syrian refugees.

Two mobile clinics regularly receive 800 people a month—but demand has skyrocketed since the USAID cuts. Last month in Aqry, 50 miles east of his headquarters, police turned away 300 people desperately pounding on the door for services. Previously, they rarely treated more than 20 people per day. Now they receive 70, and the regular demand has doubled.

“Jesus gives me patience,” Bahro said.

Maao had kind words for Christian ministries serving in the area. Through a different organization, he benefited from English language, digital skills, and leadership training. Ongoing mentorship helped him find secular work outside the camp, and he regularly seeks their advice and prayer.

A medical need prompted his harrowing journey to Europe. In 2016, his brother suffered a stroke and could not find local treatment. Frustrated by limited medical service in their isolated setting, in 2021 Maao and his nine-year-old nephew flew from Baghdad to Belarus to join a caravan of migrants. Many were seeking a better life in Europe. Maao’s goal was family reunification through asylum so that his brother could get the treatment he needed.

Relying on referrals for smugglers, they crossed borders while freezing in a forest, fleeing from police, and figuring out how to recover from tear-gas exposure. After two months in and out of detainment, their multination saga finished legally in the Netherlands, where they obtained temporary residency. His brother, his sister-in-law, and their three other children were subsequently welcomed, and his brother’s health is steadily improving.

Life is difficult in the diaspora, Maao said. The Yazidi religion places great importance on local shrines—and there are no comparable buildings outside their homeland. Members are required to marry within their religion. And to limit community mingling with outsiders, basic education had been discouraged until recently.

Maao sees little hope for Yazidis in Iraq. Muslims accuse them of “devil worship,” claiming their peacock angel resembles Lucifer. He says they suffer regular religious discrimination. And as long as his people remain dependent on outside help, they will only continue to stagnate in the villages of Sinjar.

He is critical of the USAID cuts but dreams of a future when American help is no longer needed. He is studying at college as he volunteers to help other refugees. Last January, he told his story to a gathering of 70 social work students hosted by Refugee Work Netherlands. Few of them had even heard of his people, though afterward, some joined his call to help. But a new generation of Yazidis—scattered across the diaspora—can obtain the skills needed to raise awareness and uplift their community in Iraq, he said.

Maao’s desire is to teach his people AI. Ten years ago, he was ignorant of email. He would love to open a center to teach the digital skills he has received and enable Yazidis to develop their economy. In the meanwhile, he has learned to be resilient, has grown in confidence, and sees a future of purpose for himself and his people.

“I miss my family,” he said. “But I can do more for them here than in Sinjar.”