“I have lived most of my life,” writes Alec Ryrie, “in the comforting moral certainties of the age of Hitler.” But that age, Ryrie believes, is drawing to a close—and what are we to do when the moral consensus of anti-Nazism no longer unites the West? Is a new synthesis of values possible, or are we doomed to social and political disintegration?

Moreover, what led us to think the legacy of World War II could be the singular load-bearing structure for our culture’s values? In replacing Jesus Christ with Adolf Hitler as the focal point of our collective moral imagination, we traded a positive vision (what we love) for a negative one (what we oppose). That tradeoff may have worked for a few generations, but with living memory of the Holocaust passing away, the shadow of the Third Reich is withdrawing as well. What will follow it? Will we remember the right lessons of the last century? Or will what comes next be even worse?

These are the questions that animate Ryrie’s new book, The Age of Hitler and How We Will Survive It. Ryrie is an eminent British historian of Protestant Christianity who has written widely about doubt, secularism, and the English Reformation. The Age of Hitler is something of a departure for him. On the one hand, it is brief, punchy, and addressed to a wide audience. On the other, it is somewhat outside his wheelhouse: a piece of contemporary cultural commentary, an intervention in the culture wars common to the US and UK, complete with a proposal for how to move beyond them.

For Ryrie, that analysis is the key that unlocks everything else. And, as I’ll elaborate below, he’s wise to focus his attention there, because once Ryrie turns to advice, the book begins to wobble.

The diagnosis comes in the form of a story. It narrates how English-speaking North Atlantic cultures transitioned with remarkable speed from Christianity as the default setting for public life and moral discourse to—well, something else. Ryrie is under no illusions that the 18th and 19th centuries were a high point for obedience to the Sermon on the Mount. Rather, he has in mind the givens and nonnegotiables of everyday life, the heroes and stories held up as exemplars, the standards against which success or failure is measured. If hypocrisy is the homage that vice pays to virtue, then these cultures were once full to the brim with Christian hypocrisy, not some other kind.

In Ryrie’s telling, the three decades or so that spanned the two world wars had two major effects on the church’s standing in the West. First, our moral credibility crumbled as Christians on all sides readily signed on to nationalist visions of total war. In fact, for some time, many Christians among the Allied nations were far less concerned with the evils of the Nazis, fascism, and antisemitism than they were with the Bolsheviks and Soviet Communism.

Yet once the true depths of Hitler’s evil and the Final Solution came into full view, an important shift occurred. The “world” in World War wasn’t a reference to the global nature of the conflict so much as to what was at stake in its outcome: the world itself. This world was a particular civilization with a universal scope, what came to be called “Judeo-Christian civilization.” American forces turned out to be fighting for something more than Christendom; it was for a pluralist vision that included Jews and Catholics, at least, and maybe more to come.

In 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt identified the principles of that “more” by reference to four freedoms: “freedom of speech and of worship, and freedom from want and fear. America sought these freedoms,” as Ryrie summarizes Roosevelt’s speech, “not only for itself but ‘everywhere in the world.’”

Here was a truly comprehensive vision. The four freedoms weren’t a matter of race or culture or even a particular policy. They concerned the whole of humanity. All people deserved or possessed them simply because they were human. Thus they were not civil or constitutional or legal rights but human rights. And human rights are neither defined by borders nor granted by governments. They were presented, to borrow the words of Thomas Jefferson, as “self-evident” and “unalienable.” And so, in the wake of Hitler’s defeat, the United Nations was formed in 1945 and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was promulgated three years later.

Meanwhile, Hitler became a symbol of pure evil. He encapsulated everything the victorious Allies aspired not to be. His misanthropy, racial vitriol, and lust for domination became the moral counterpoint to universal human rights. The fact that he came so close to triumph yet was soundly defeated by British and American power neatly proved that might doesn’t make right, and that truth and goodness—democracy and human rights—will inevitably win out in the end.

Hitler thus became a fable, a moral just-so story around which an entire constellation of values gathered in orbit. There is one thing everybody in the West has known for the past 75 years: namely, that Adolf Hitler—who stands for Nazi Germany, genocide, dictatorship, antisemitism, and racial supremacy—is evil.

The “age of Hitler” in Ryrie’s title is not, then, about the 1930s and ’40s. It’s about our own times, the “postwar” period of the 1950s and ’60s down to the present.

As Ryrie writes, “A century ago the most potent moral figure in Western society was Jesus Christ. Now it is Adolf Hitler.” No longer a cross or crucifix but instead the swastika is the talisman of our time—a talisman of evil, to be sure, yet far more powerful than any other cultural or religious symbol.

At the political level, anti-Nazism became a doctrine that informed both domestic and foreign policy. Pluralism, internationalism, and the long march of human rights were good; religion, nationalism, and particular moral and cultural traditions were suspect. Certainly, any long-standing custom or belief that maintained or inscribed persistent differences, divisions, or hierarchies between groups or kinds of behavior was bound for the chopping block. After all, this was the open society. Proscription was passé.

At the cultural level, the morality tale of World War II became embedded in popular novels and films. From Lord of the Rings to Star Wars to Harry Potter, the Saurons and Emperors and Voldemorts—holding the world in thrall via the Ring or the Force or the Dark Arts—could not be appeased, lest tyranny prevail. They must be defeated at all costs in a cosmic battle between “the children of light and the children of darkness.”

At this point you might be wondering: What’s so bad about all this? Wasn’t Hitler the embodiment of evil? Isn’t it goodwe can all agree on that? Aren’t human rights an accomplishment to be celebrated? Aren’t Tolkien and Lucas and Rowling reinforcing messages we want to shape our children’s moral imaginations?

Yes, Ryrie responds, but only up to a point. He’s glad for the postwar legacy of human rights and democratic pluralism. He’s not a reactionary and not exactly a postliberal either. His stated problem isn’t with the Enlightenment per se.

No, Ryrie’s concern is that Hitler cannot bear the weight our society has placed on him. General agreement that Hitler was evil is, simply put, insufficient either for a positive moral vision or for the challenges facing us in the coming days.

Ryrie offers four reasons to support this claim. First, he objects to “the whole business of using an exemplar of evil to set our moral compass. It means that we now know what we hate, but we do not know what we love. Or rather, the things that we do love—human rights, liberty—are quite deliberately vacant categories: their whole point is that they are undefined spaces in which individuals and communities can find what they love and pursue it.”

We lack, in short, a sense of “the good.” Just as many refer to “my truth,” they also imply “my good.” Are there no goods in common upon which we can agree?

Second, Ryrie suggests that the lessons learned from World War II are a mixed bag. As a matter of historical fact, most armed conflict is not a world-bestriding war between good and evil and does not—should not—end in unconditional surrender. Most of the time, instead, war is muddled, muddy, and gray. It concludes unsatisfactorily via diplomacy and deal-making. The result is decidedly uncinematic: backroom trades, imperfect treaties, and negotiated settlements in which villains walk away unpunished by divine justice.

Third, Ryrie urges us to step back and face the obvious: World War II was a war. Should any war, however justly fought, be this central for a society’s morals? Is every tyrant a Hitler, every slaughter a Holocaust, every armed conflict a hair’s breadth removed from apocalypse? Perhaps filtering the world through the lens of the Nazis is not a reliable guide for navigating geopolitics. We need other ways of seeing, other stories and points on the compass to show us the way.

Fourth and finally, Ryrie wants readers to understand a fundamental irony, even a contradiction, at the heart of Western anti-Nazi ethics: They are particular, not universal.

To be sure, they admit no limit on their scope or jurisdiction; they claim a boundless application. That is what makes them so powerful. But it’s also what makes them so dangerous. An infinite moral principle can never be gainsaid. If every evil is Hitlerian and the stakes are always the very survival of human rights, then we can never surrender, never compromise, never retreat. Sam and Frodo must destroy the Ring; Han and Luke must blow up the Death Star. Isn’t that the way the story always ends?

No, not in real life. And here the particularity of Western values in the age of Hitler reveals its special brittleness. Belief in universal human rights is just that: a belief. Or better, a faith.

Ryrie calls it “the new faith of a secular age.” It is a doctrine so fixed that to question it “is almost to commit a kind of blasphemy.” And yet, he notes, “We all know, if we stop to think about it, that the modern doctrine of human rights is a castle in the air. It is a defiant existential assertion of values … without any firm foundation.”

In practice, rights are not self-evident—as evidenced by the fact that most human beings for most of their history have lacked any concept of them in the first place. From a Christian perspective, something like human rights can be preserved by grounding them in a doctrine of creation and its Creator. But then, from the postwar political perspective, human rights were meant to replace such a doctrine, offering a secular, pluralistic alternative to it.

Ryrie does not cite the philosopher Alasdair MacIntyre, but his thought hangs over the whole book. In his 1981 work After Virtue, MacIntyre argued that the concept of universal human rights depends upon “a socially established set of rules” that “come into existence at particular historical periods under particular social circumstances. They are in no way universal features of the human condition.” He continued, “In the United Nations declaration on human rights … what has since become the normal UN practice of not giving good reasons for any assertions whatsoever is followed with great rigor.”

Hence MacIntyre’s famous conclusion: “The truth is plain: there are no such rights, and belief in them is one with belief in witches and in unicorns.”

For Ryrie, that’s a bridge too far. While he agrees with MacIntyre that human rights are a “mirage,” he doesn’t want to jettison them just yet. He thinks the development of the concept of universal human rights is a moral achievement worth conserving. What he refuses to affirm, however, is that they are self-evident or culturally nonparticular. Indeed, their international application is a unique achievement of one group of nations in response to one war. That’s about as particular as an idea can get.

Above all, Ryrie argues, human rights are not and never could be adequate on their own. He demonstrates this point with reference to current events. The Allied victory over the Nazis is not a template for responding to climate change, for example. The same goes for the pandemic. Our eagerness for Hitlers to blame and topple may root out some bad actors, but viruses aren’t human agents and the planet’s temperature won’t respond to threats of force.

Or consider arguments about gender. It isn’t hard to see how or why the logic of human rights was rightly extended to women and African Americans in the 1960s and beyond. In recent years, however, fierce disputes between secular feminists regarding transgender surgery and hormone therapies illustrate that human rights are not self-interpreting; one must appeal beyond them to norms and goods that rights themselves do not supply. Suddenly the author of Harry Potter’s triumph over the Dark Lord comes to be portrayed as a dark lord herself.

Ryrie’s aim with the book is to show that not only we have been living in the so-called age of Hitler but also, like it or not, that age is coming to an end. “Instead of a singular event,” he writes, “Nazism now appears simply as an extreme example of a long, continuous history of racial persecution and genocide, a history which has crossed many continents and centuries and is still going on, and which, perhaps, has no prospect of ever coming to an end.”

Because Ryrie thinks the anti-Nazi consensus was never meant to last, he doesn’t see its end as a bad thing. What matters is what comes next.

So in the final two chapters of the book, Ryrie addresses first secular progressives then conservative traditionalists about what it would mean for either group to forge a new synthesis between the postwar program and ancient religious and moral traditions. In this sense the age of Hitler is not quite at an end; its end has begun, but it remains unclear what will take its place once it is well and truly behind us. Ryrie purports not to care who gets to determine the heir. He is confident, though, not only that someone must but also that someone will—and whoever does will have the power to set the terms of debate going forward.

These chapters are by far the weakest part of the book, full of vague hand-waving and simplifications bordering on caricature. The book’s overall argument is well made, provocative in all the right ways, and utterly persuasive. So it is all the more surprising when Ryrie lapses into a kind of bothsidesism or above-the-fray neutrality.

Passive sentence constructions betray him time and again (emphases mine): “Questions of racism and racial justice have acquired a new moral urgency”; freedom of speech “has begun to sound like a far-Right code phrase or dog-whistle”; talk of the good “feels not just old-fashioned but almost imperialistic in our current moment.”

Does it? To whom? When, where, and why? This sounds like the zeitgeist, not of society in general but of center-left social media. The resulting atmosphere of everyone knows and of course beclouds what solid advice Ryrie does have to offer in the closing section. Riffing again on MacIntyre, he urges progressives and conservatives alike to tap into the deep roots of particular traditions and to discover the ways they might enrich, rather than replace, the shallow roots of postwar ethics.

Where Ryrie departs from MacIntyre is that he does not locate the problem in political liberalism as such. I could not tell if this was conviction or coyness on Ryrie’s part. Postliberalism is in vogue today, and it would have been helpful to have clarity from Ryrie on whether he thinks that moving beyond the age of Hitler entails moving beyond liberalism too.

At this point, it’s worth mentioning two works that complement The Age of Hitler, in a sense filling out its arguments. One is Democracy and Populism: Fear and Hatred, published in 2005 by John Lukacs—one of the world’s greatest Hitler historians. “Hitler was not a ‘demonic’—that is, at least by inference, an ahuman and ahistorical—phenomenon but a historical figure,” Lukacs contends in another work, despite what our usage of Hitler as a moral absolute might suggest.

The second book is Two Faces of Liberalism, published in 2000 by the English philosopher John Gray. I commend these to readers because each of them anticipated our present moment and offered what I take to be stronger (if somewhat divergent) prognoses and recommendations than Ryrie’s.

Having said that, I think Ryrie is right about many things—about the “age of Hitler,” for starters, and about the need to find our way beyond its limitations. He’s right, furthermore, that tradition and religion are not obstacles but vital resources for this challenge. The question he leaves us with, then, is twofold. One: How should we—whether the “we” of the North Atlantic, of the United States, or of the church—understand liberalism in the transition from the age of Hitler to something else? Is it part of the problem or can it be part of the solution?

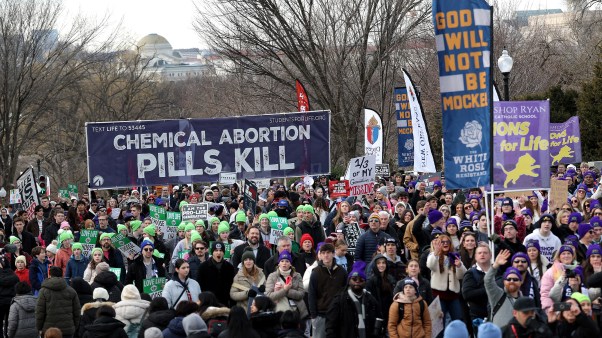

And two: What role might Christians have to play in this transition? Ryrie suggests humility, repentance, and even silence. This retreat to the political wilderness would not be for self-preservation, as in Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option,but in contrition for our histories of sin, exclusion, and violence. He judges the recent muscular reassertion of public Christianity on the right to be hollow and self-defeating, citing declining faith and church attendance as the unavoidable consequences.

That’s an empirical claim, and there are some hints in the data that it might be false. Be that as it may, the question is a matter of principle: If Hitler took the place of Jesus in our culture’s moral vision, can we imagine Jesus resuming his place? Was it a good thing for Western society to be hypocritical as measured by Christian rather than other standards? Or should we bid good riddance to an order that pays tribute to the Lord by failing to obey his commands?

Whether or not it is possible to return to a truly religious culture in the West—and it may not be—the issue is whether it is desirable. Having criticized Ryrie for keeping his cards too close to the chest, I’ll show mine: I think the answer is yes. Given the alternatives, it is much to be desired. Beyond the age of Hitler, it is worthy of our hope and of our labors to seek to live in the age of Christ.

Brad East is an associate professor of theology at Abilene Christian University. He is the author of four books, including The Church: A Guide to the People of God and Letters to a Future Saint.