The American Western, onscreen and on the page, usually goes something like this: a sleepy frontier town, maybe in the plains, maybe tucked between soaring mountains. There’s a train depot, a few horses, a sheriff who keeps the law in a place otherwise pitched as lawless. A villain rides in. A damsel needs rescuing. And through it all, rugged individualism is valorized. Civilization arrives not through institutions but through grit and self-reliance. As Scott Frank’s TV series Godless articulates, the West was not just wild—it was Godless.

Those John Ford films, Clint Eastwood’s brooding and gunslinging characters, or even Kevin Costner’s more recent and commercially flat Horizon, have helped shape our nostalgic mythos of the West. But what those dramas and beloved novels leave out—from Cormac McCarthy to Larry McMurtry—is the radically diverse labor of building the West. The real West included Black homesteaders, women leaders, Mexican and Indigenous communities whose stories have seldom found a place in history books. It was not solely grit or conquest that animated their actions, but complicated, earnest Christian charity. And the challenges they faced—displacement, spiritual responsibility, and the tensions between charity and power—echo today in how many churches respond to a wide range of issues.

The story at the heart of my book, Black Moses: A Saga of Ambition and the Fight for a Black State, takes shape within this world, which was built in part by reformers who sought to remake freedom on their own terms. Elizabeth Rous Comstock, a Quaker and a humanitarian in Kansas, was one of these reformers. On a summer day in 1879, Comstock wrote a letter to John Pierce St. John, the governor of Kansas, conveying a sense of urgency and mission about a humanitarian crisis unfolding before her eyes. Kansas had only recently entered the union as a Free State against the wishes of neighboring Missouri and much of what had been the Confederacy. Thousands of formerly enslaved Black people were pouring into Kansas, searching for a promised land that, in reality, was unprepared to receive them. Comstock, who was born in England, had traveled widely and raised substantial funds for humanitarian causes. But now she was facing something entirely new.

In response to the influx of Black migrants, who would come to be called “Exodusters,” Comstock proposed gathering up “bedding & clothes & what I can in the way of more substantial metallic sympathy”—her evocative phrase for financial support. She was charitable, but her mission surpassed simple charity; it was a deeply rooted theological conviction that God had called her to help fix what society had broken.

Comstock and her close friend, Laura Haviland, represented perhaps the most earnest impulses of American Christianity in the fraught post-Reconstruction period of the late 19th century. Both were active, deeply committed Christians who emphasized practical needs—such as food, shelter, and clothing—as integral to spiritual outreach. Comstock, with her extensive networks among Quakers, saw her work as a continuation of abolitionist efforts.

After the devastating collapse of Reconstruction, she traveled extensively, even venturing to her native England, to raise over $60,000 for humanitarian efforts—an enormous sum which today would equal about $2 million. Her goal, among other things, was to establish the Agricultural and Industrial Institute for Refugees in Kansas, an ambitious project that sought to offer Black migrants not just temporary relief but training, work, and a Christian education.

Comstock explicitly connected her work to the legacy of Abraham Lincoln, declaring that Lincoln had “crowned the labors of abolitionists,” leaving it “to the Christian philanthropists of our age to crown his great work.” Meanwhile, Haviland shared Comstock’s mission but approached it quietly, emphasizing steady, consistent service. Raised as a Methodist, Haviland had spent years before getting to Kansas working along the Underground Railroad to help enslaved people reach freedom. Haviland knew from experience that liberation required not just physical freedom but spiritual and intellectual empowerment. And her quiet, persistent efforts complemented Comstock’s energetic public appeals, forming a powerful, if sometimes overlooked, Christian response to a national crisis.

The two women were spearheading efforts in a time when they themselves had limited rights and privileges. Their engagement was pioneering not only for racial justice but also for the roles women could publicly occupy. Yet the story of Christian engagement—particularly among white Northern Protestants—in the Black migration westward is complex. Comstock and Haviland’s efforts, laudable and sacrificial as they were, occurred amid a Northern Protestant culture that championed abolitionist ideals while still clinging to paternalistic views of Black migrants, often framing them as objects of charity rather than as partners in self‑determination.

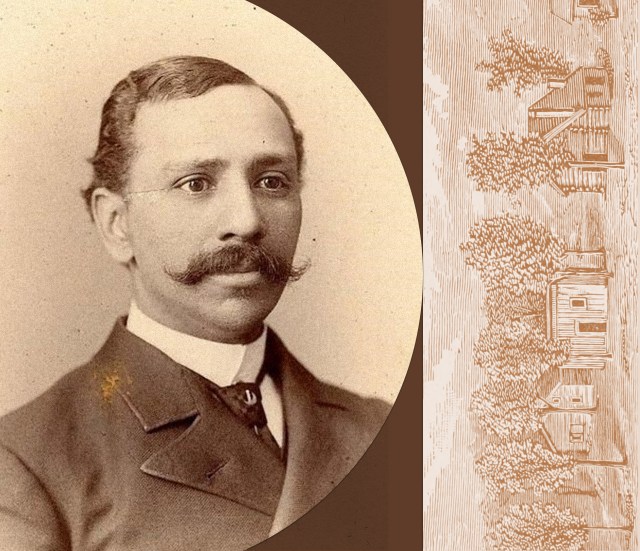

At the same time, another form of religious engagement was taking shape—one forged not in the parlors of benefactors like Comstock and Haviland but in the political imagination of Black leaders seeking sovereignty. Edward P. McCabe, an influential Black leader, advocated passionately for the Black migration westward and saw the church more as an organizing and political vehicle rather than merely a spiritually transformative one. McCabe’s religious convictions are unclear, but we know that he leveraged biblical motifs, like Moses confronting Pharaoh, as a potent political tool for mobilization. He positioned himself as a political Moses and met with President Benjamin Harrison to lobby for the creation of an all-Black state. McCabe and his allies also dispatched thousands of agents across the South to recruit migrants, asserting that Black people deserved self-rule free from white oversight.

Illustration by Christianity Today / Source Images: WikiMedia Commons

Illustration by Christianity Today / Source Images: WikiMedia CommonsAt the time, the Christian faith was functioning both as a balm and as a banner—as a source of comfort and as a call to power. While Comstock and Haviland focused on moral reform through charity, McCabe harnessed the faith as political leverage. Despite their different methods, they all inherited a legacy that began about two decades earlier with the New England Emigrant Aid Company—a coalition of Northern church groups who sent settlers to Kansas not just to populate the plains but to ensure freedom took root in the state while it was still contested soil.

By the 1870s, however, the battle had shifted from merely ensuring Kansas remained free to actively supporting those who came seeking true autonomy and freedom after the catastrophic failure of Reconstruction. Comstock, Haviland, and the Black Exodusters themselves were not only participants in a continued struggle over who would truly be able to claim freedom in America—a battle that outlasted the Civil War—but also pioneers seeking to perfect the promise that the war and Reconstruction had left incomplete.

Gov. St. John eschewed marshaling state resources in response to the mass exodus. Instead, he reframed the crisis as a charitable endeavor, creating the Kansas Freedmen’s Relief Association—a humanitarian effort that eased political pressure for himself but left the Exodusters dependent on the moral economy of Northern benefactors. The organization—which Comstock, Haviland and others worked through—exemplified the promise of Christian charity, as well as the challenges that came along with these efforts. It aimed “to relieve the wants and necessities of destitute freedmen.” But its work also raised uncomfortable questions, some voiced by Black leaders at the time, others articulated more fully by later critics: Were some Christians inadvertently perpetuating the very racial hierarchies they sought to dismantle? Were their actions driven by authentic solidarity or a sense of superiority?

The Black exodus to Kansas was undoubtedly a humanitarian emergency. Immediate aid championed by Comstock and others addressed urgent, basic needs, but it failed to recognize that the migrants had also come to build lives for themselves. The charity of the exodus era, however well-intentioned, often came from a place of superiority, seeing Black migrants as objects of Christian benevolence rather than equals in God’s kingdom. Comstock herself, despite her genuine concern, approached her work from the prevailing mindset of white reformers—expecting Black migrants to shed who they were to, from her view, improve themselves.

As historian Kim Cary Warren argues in The Quest for Citizenship: African American and Native American Education in Kansas, 1880–1935, reformers like Comstock sought to “make worthy American citizens out of Indians and African Americans.” The salvation critical to their work wasn’t merely from sin to a life redeemed by Christ and lived in service to God. It was tainted by what they saw as ethnic minorities who “had been anchored in thousands of years of slow evolutionary development leading to a hierarchy of races.” Some reformers sought to remove cultural differences and remake Black people, most of whom were already Protestants, in their own image. One reformer, Ednah Cheney, expressed a desire for “controlled religious expressions for the shouting and noisy prayer meetings” that she characterized as the “religion of the Negro.” And generally, when the reformers spoke of race, Warren notes they “heavily emphasized their belief that whites inherently possessed superior capabilities” and, in turn, “allowed racism to emerge from their own benevolent efforts.”

If Comstock’s approach reflected the limits of benevolence, McCabe embodied a different, insurgent vision: one where Black people would no longer be mere recipients of aid but architects of their own political destiny. McCabe, soon after coming to Kansas, would go on to become the state’s auditor, and then leader of a Black migration movement, and then one who would rally thousands behind his Black-state dream. But despite his stature and organizing prowess, the vision faltered against fierce white political resistance, federal unwillingness to grant such sovereignty, and the immense logistical challenge of sustaining a mass migration.

Caleb Gayle is an award-winning journalist and professor at Northeastern University. He is the author of the book Black Moses: A Saga of Ambition and the Fight for a Black State.