At Bil el Burbur Primary School in Wajir County, Kenya, 35-year-old Sween Ambeyi sits on the bare ground in the hot sun and points to a small blackboard hanging on the acacia tree behind her. The 16 Muslim seventh graders—6 girls and 10 boys—sit separately. Though a hijab covers her, Ambeyi is a Christian, as are four out of five Kenyans, according to the 2019 census.

Although Kenya guarantees freedom of religion, Ambeyi cannot worship openly in Wajir due to community pressure. Muslim community leaders force her to wear a hijab. “It is either you obey or be sacked,” Ambeyi said. “When you cover your face like them, they will regard you as one of their daughters. Otherwise, they will beat you up for wearing skirts and other dresses.”

She also has to hide her Bible reading. “I can open my phone and read the Bible, then pray silently,” she told CT. “That’s the only option.”

She also faces bullying and harassment. Community leaders do not allow Ambeyi or other non-Muslims to touch a Quran. Female students and fellow teachers mock her for not having experienced female genital mutilation, a common practice in the area.

Ambeyi said she can’t punish or argue with male students. “Even if a male student is in the wrong, you have to keep quiet, because they will rush home and come with their mothers.” In this culture, mothers fiercely protect their sons. Ambeyi added that the mothers start conflicts with the teachers.

But for Ambeyi, quitting is not an option. Ambeyi said unemployment would be worse, and going back to college to start another career would take years.

When she graduated as a teacher in 2019, Ambeyi worried she wouldn’t find work. She took a friend’s suggestion to search for a job in the majority-Muslim counties of northeastern Kenya. Schools there struggle to hire teachers due to instability caused by the terrorist group Al-Shabaab. (The group killed five people in April 2025 and has targeted teachers in the past.) That’s how she ended up in Wajir a year later.

“You see, life rotates around finance,” Ambeyi said.

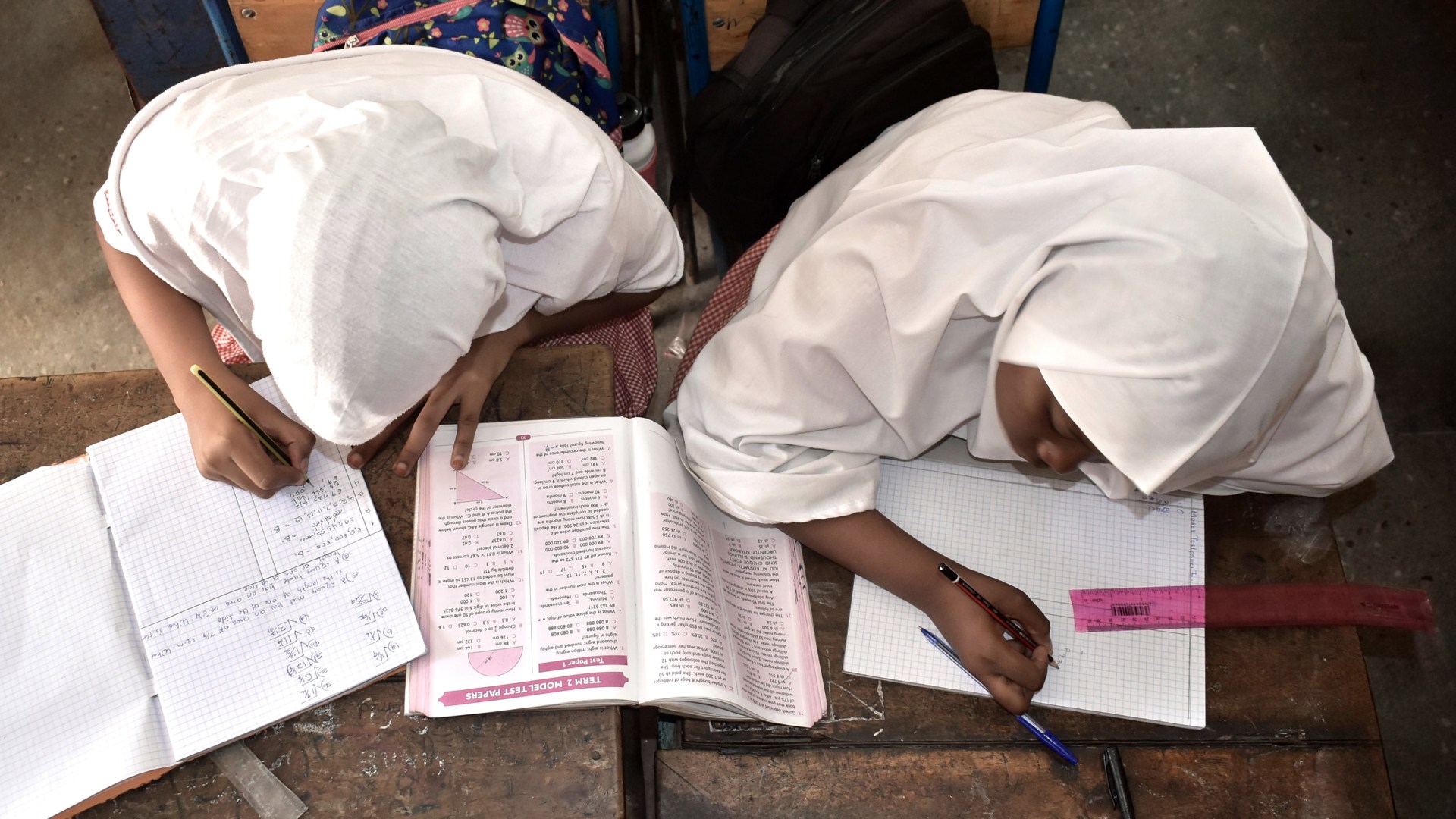

Ambeyi first took a temporary position at Machesa Primary School for a monthly salary of 10,000 Kenyan shillings ($77 USD) and started applying for permanent public school jobs. She hoped to gain enough experience at Machesa to qualify for a job with a steady salary and opportunities for promotion. Four years later, the government posted her at the better-paying (about 34,000 shillings or $264 USD) but even-more-remote Bil el Burbur, a school with 300 students and only 4 teachers. Until she can qualify for transfer closer to her home in Western Kenya, Ambeyi has to blend in with the Islamic community in Wajir.

Kenya’s teachers face a high unemployment rate, a factor that pressures Christian teachers like Ambeyi to work in schools hostile to their faith. Around half of qualified Kenyan teachers are unemployed despite severe understaffing at many schools, especially near the Somalian border. Many teachers avoid Muslim-majority counties due to threats from terrorists, which increases competition for more-desired positions. Julius Ogamba, Kenya’s education cabinet secretary, blamed the unemployment crisis partly on uneven teacher distribution across counties. Inadequate salaries, slow government hiring processes, and a mismatch between popular high school teacher specialties (like humanities) and in-demand subjects (like science) may worsen unemployment and burnout.

Media outlets have blamed bureaucracy and corruption for teachers’ underemployment. Politicians allegedly circumvent the Teachers Service Commission (TSC) and give appointment letters to their relatives or sell them to the highest bidders.

Despite having completed college degrees and one-year internships, new teachers must seek temporary positions or private-school jobs before qualifying for permanent roles in public schools. But even then, their spots aren’t guaranteed. The TSC stirred controversy in 2024 for failing to guarantee probationary teachers permanent positions, forcing them to reapply for their jobs.

Some teachers say their peers resort to bribing TSC officials to get a position. For those who don’t offer bribes, such as Ambeyi, financial need can drive them to take jobs from equally desperate schools.

Ambeyi hopes to get a transfer to a school in a majority-Christian area, but Burton Wanjala—a teacher who has worked in a Muslim-majority area for five years—said getting a transfer is not that easy. Wanjala tried and failed several times. He explained that head teachers can only approve transfers under one of three conditions: medical reasons, replacement, or security reasons. A doctor must recommend a medical transfer. Replacement requires swapping positions with a willing teacher from another school. Security reasons require a clear threat, such as when the killing of nonlocal teachers by Al-Shabaab led to a mass exodus of teachers in 2014 or when the government withdrew all nonlocal teachers in 2020.

Wanjala said head teachers who allow transfers rarely receive replacements due to the shortage of teachers in the region, so they may not want to approve these switches. But, Wanjala said, “you can bribe bosses at the Teachers Service Commission, and you will receive a transfer letter directly without passing through the head teacher.”

The TSC requires newly employed teachers to work at their assigned schools for a minimum of five years before seeking a transfer. Ambeyi has served for less than two. She said she knows of teachers who have managed to get transfers approved before the five-year mark. But as a Christian, Ambeyi won’t pay a bribe or fake an illness. As she waits, Ambeyi prays Al-Shabaab won’t attack her.

“I know one day God will open a door for me and get a transfer to my home area,” she said. “As for now, I have to continue complying to these conditions, as long as I don’t fall in trouble with the Somali Muslim community.”