As a child growing up in Seoul, I read the story of Yu Gwan-sun, a teenage girl who was imprisoned, tortured, and killed by the Japanese colonial police for participating in Korea’s March 1st Movement to overthrow Japanese rule in 1919.

In elementary school, I watched a TV drama about Korean “comfort women” forced into sexual slavery during Japan’s military expansion. In history class, I learned that the Japanese colonial government did many things to erase our Korean identity, like banning our language, replacing our names with Japanese names, and making us bow down to the Japanese emperor.

At church, pastors and teachers often drew parallels between the Japanese occupation of Korea and the Exodus narrative in the Bible. “Japan was like Egypt,” they would say. “We were like the Israelites, oppressed but freed later.”

These widespread portrayals of Japan as Korea’s brutal oppressor created in me a deep discomfort and fear toward the Japanese people, even though I had never met any at the time. Because I was a descendant of people who had suffered such evil treatment, it seemed only appropriate that I should also take up my ancestors’ hostility toward our nation’s enemy.

Unfavorable sentiments toward Japan and its people often surge in the lead-up to August 15, when South Korea commemorates its Liberation Day from 35 years of Japanese rule between 1910 and 1945. Such attitudes are especially heightened this year, which marks South Korea’s 80th year of freedom. Many commemorative events have taken place around the country, including exhibits and writing contests evoking memories of historic oppression.

But as I’ve developed friendships with Japanese people and visited Japan multiple times, my understanding of Japan and South Korea’s complex history has changed. I no longer consider Japan as Egypt and South Korea as Israel. Rather, I view the two countries’ relationship through the lens of another biblical account: the parable of the lost son in Luke 15.

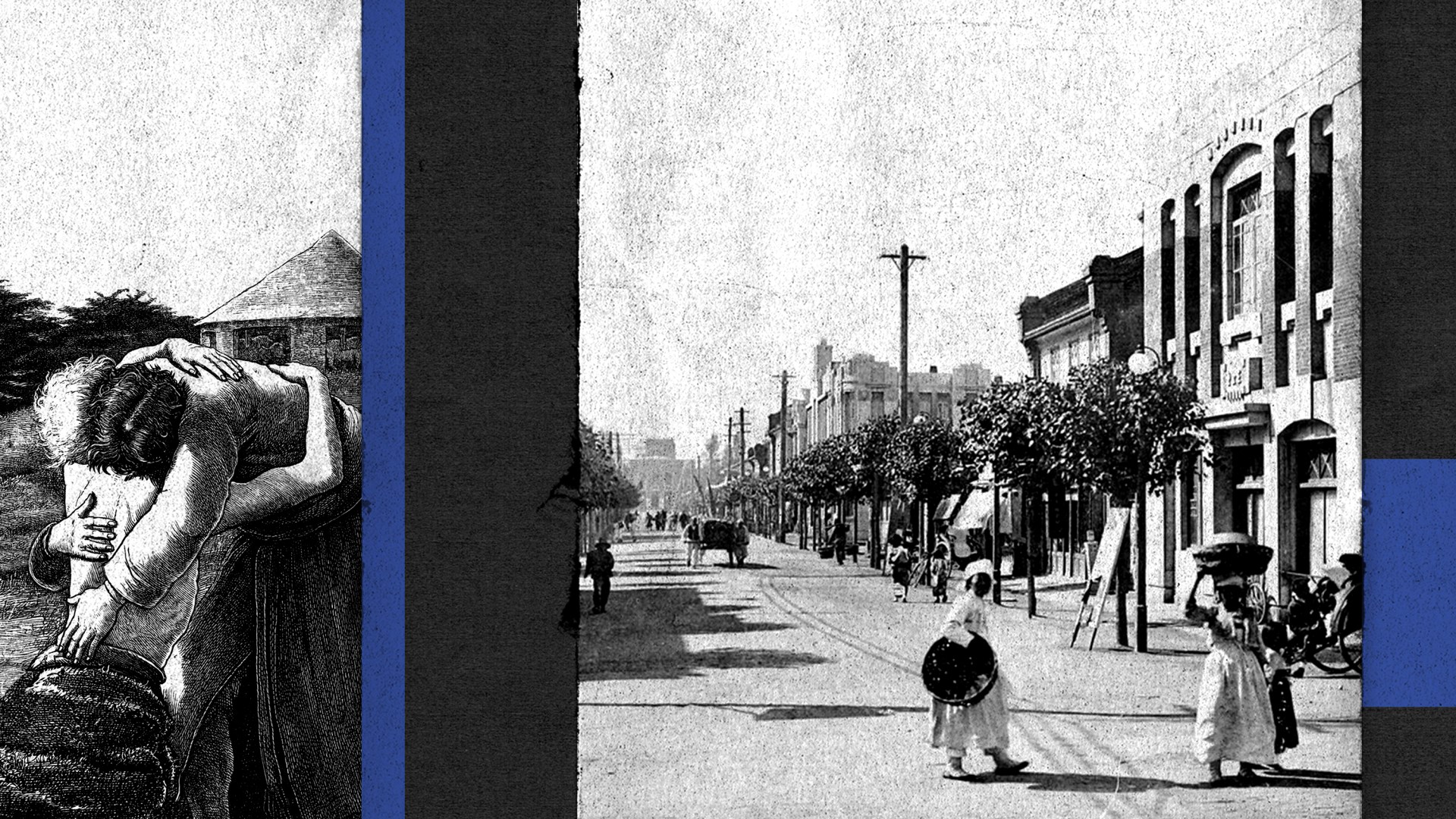

In this passage, the younger son who has squandered his inheritance returns home in desperation. Although he expects rejection, “his father saw him and was filled with compassion for him; he ran to his son, threw his arms around him and kissed him” (v. 20).

This parable highlights a father’s boundless grace toward his wayward son. Instead of rejecting him or treating him as a mere servant, the father welcomes his child with open arms. I yearn to see more Korean evangelicals view Japan in the same way: with kindness, compassion, and forgiveness, as Paul urges us to do in Ephesians 4:32.

The seeds of my journey toward a transformed perception of Japan and its people were sown through a story my grandmother told. She was born in Korea in 1924 but spent most of her early years in Manchuria (present-day northeast China), where the Japanese government had relocated many Koreans alongside the Japanese to populate and cultivate the region as a strategic territory.

At ten years old, I asked my grandmother about her time in Manchuria and her interactions with Japanese people. I expected to hear stories about hostility and mistreatment. Instead, she told me about a kind Japanese neighbor in her town.

“I did not speak Japanese very well like my brother,” my grandmother said. “My parents did not send me to the primary school, because I was a girl. But whenever this lady saw me, she always bowed politely and spoke very slowly and gently so I could understand her Japanese.”

My grandmother’s story—the only story she shared with me about her encounters with the Japanese people—shocked me. Japanese people were kind and gentle? All I had read and heard about them focused on their violent, cruel deeds. This story seemed implausible to my young ears.

Five years later, my family relocated to Indonesia. On the day of an English qualification exam for entry into an international school, I met a Japanese girl who was my age. “Hi, nice to meet you. My name is Kayo,” she said in slow, careful English. “Can we become friends?”

At first, I felt a bit uncomfortable. How could we be friends when I was Korean and she was Japanese? But we became firm friends from that day on. We swapped our favorite Japanese and Korean tunes and visited each other’s homes in Indonesia and, later, in South Korea and Japan. And whenever I was in Japan, Kayo’s family embraced me as their own.

Through my grandma’s story and my friendship with Kayo, I overcame the discomfort and fear I had inherited from my people’s collective memory. I learned that a genuine friendship based on kindness and compassion could break down prejudices and unforgiveness.

Sometimes, though, we as Korean evangelicals may think and act like the resentful older brother in the parable. When the older brother sees his father welcoming the younger son with a lavish feast, he becomes angry and refuses to celebrate with the family (Luke 15:28).

Like the older brother, who felt bitterness and animosity toward his sibling, we may also feel similarly toward Japan, criticizing the country for not seeking forgiveness from Korea for past atrocities.

Prominent Japanese leaders like Emperor Hirohito and several prime ministers have publicly expressed regret and remorse for the war. But their words often lack direct acknowledgment of wrongdoing in the past, which many Koreans consider the most important element to include in Japan’s apology. Other Japanese government leaders’ actions also overshadow these gestures as they continue to visit Yasukuni Shrine, where Japanese people venerate “Class-A war criminals”—individuals charged with planning and waging war—as gods.

While visiting Japan in my 20s as a language student, I discovered that some history textbooks there had downplayed or entirely omitted Japan’s colonial past. Because of this, many Japanese people are unaware of the suffering that Korea and other Asian nations experienced during the Japanese occupation.

My Japanese evangelical friend at seminary, Sho Ishizaka, felt deeply troubled when he learned as a teenager about the horrible things that Japan had done. When I asked Sho if he would be willing to apologize to the Koreans for his ancestors’ sins, he responded without hesitation: “I will apologize. We Christians will apologize—over and over again.”

Other Japanese evangelicals have also made sincere efforts to express their repentance.

In 1997, the Nippon Revival Association, representing 500 Japanese churches, issued a formal apology: “We … make clear our responsibility in World War II … and wholeheartedly apologize for it, declaring August 15 and December 8 [to commemorate the day Japan attacked Pearl Harbor] as ‘Days of Fasting and Repentance.’”

Japanese pastor Reiji Oyama visited South Korea multiple times from the 1960s until he died in 2023 to apologize to Korean Christians and surviving comfort women. In 2019, he visited the memorial site of a church massacre in Jeamni, South Korea, with 16 other Japanese church leaders to offer an apology. Japanese colonial police had burned the church down in the aftermath of the March 1st Movement in 1919, killing 29 Koreans as a result.

Like my friend Sho, Oyama said he would apologize until the Koreans told the Japanese people, “Now that’s enough.” It appears that Korean evangelicals have not said this yet.

Forgiveness appears inconceivable if we continue to view the two countries through the Exodus narrative. But Japan is not biblical Egypt, and it is no longer Korea’s oppressor. Instead, perhaps we can conceive of Japan as a lost brother whom our Father longs to welcome home.

I am not saying history is unimportant. We as Korean evangelicals must remember our history of oppression and suffering, but we can also liberate ourselves from our long-standing grudges. Even though we may never receive the perfect apology we desire from Japan, we can walk in the spirit of forgiveness today. Forgiveness—graciously given and received—can transform our relationship with Japan and its people.

For Japan, August 15 was not liberation day. It was a day of devastation, when the two American bombs which fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki revealed that their emperor, whom they believed to be an invincible god, was merely human.

Emperor worship was a central tenet of state-sponsored Shinto in Japan. It featured prominently in the country’s wartime propaganda, fueling the military’s efforts and calling citizens to sacrifice their time, resources, and even lives. Japan’s military leaders promised their soldiers that dying in battle, especially through kamikaze or suicide missions for the emperor’s sake, would grant them a place of honor in the Yasukuni Shrine.

When Japan lost the war, its people felt disappointed in their military and government, as they had deceived the people about the emperor’s divinity. “The defeat proved that the Japanese were not god’s people after all,” Sho told me.

This sense of spiritual disillusionment may have led to all traditional religions, including Shinto, dwindling after the country lost World War II in 1945. Although the Japanese church grew briefly through Western missionary efforts, this growth has plateaued since the 1970s. Today, Japan remains the second-largest unreached people group in the world. Less than 1 percent of the Japanese population identifies as evangelical.

In contrast, South Korea experienced remarkable spiritual growth and eventually became the second-largest missionary-sending nation in the world. One in 5 Koreans are Protestant. But Korean evangelicals must humbly remember that our country was once a lost people too, saved only by the grace of God who sent missionaries to our nation.

Japanese believers contributed to the growth of Christianity in Korea from the late 19th century to the end of World War II by training Korean pastors in Japanese seminaries and sending missionaries to Korea. The recently released documentary film Mumyeong (Nameless) follows two such missionaries: Masayasu Norimatsu, founder of Dongshin Church in Suwon, and Naraji Oda, who opposed Japan’s enforcement of emperor worship in Korea. Both devoted their lives to serving the Korean people, even as fellow Japanese citizens perceived their sympathy for the Korean people as treacherous at times.

As cultural appreciation and exchanges rise between the two countries, whether through the influence of Korean pop, Korean dramas, or Japanese anime, Korean believers can capitalize on this growing openness to reach the lost in Japan.

About 1,200 Koreans are currently in Japan as long-term missionaries, a Korean mission survey conducted in 2023 revealed. This reflects a shift in missionary deployment, because Japan has long been shunned for being a “graveyard for missions.”

Even as Korean missionaries are more willing to reach Japan, evangelicals in South Korea can create opportunities to talk about Christ with Japanese residents and visitors in their midst. Korean churches might extend hospitality through homestay programs, similar to the temple stays that Buddhist temples offer to tourists. Or believers can invite people to gospel and K-pop concerts, as Korea-based Onnuri Church has done through its Love Sonata programs in Japan.

As Korean evangelicals who have forgiven and have been forgiven, we must not pass resentment and unforgiveness to the next generation. This year, I am teaching my kids Japanese in anticipation of our reunion with Kayo and her family in South Korea and Japan next summer.

Kayo is teaching herself Korean. “I am learning Korean because you have been so kind to me by learning Japanese for me,” she said.

It is Christ alone who can dismantle the “dividing wall of hostility” between the two peoples once and for all (Eph. 2:14). As Korean believers, we can also chip away at this wall through breaking down stereotypes, reframing the narratives we tell ourselves, and fully giving and receiving forgiveness from a country that once oppressed us. As we do so, we can come to see each other as we truly are: brothers and sisters who were once lost but are now made one in Christ.

Ahrum Yoo is a PhD student in Old Testament at Dallas Theological Seminary.