This is part two of the Eddy family’s story. To read about the Eddy missionaries in Sidon, click here.

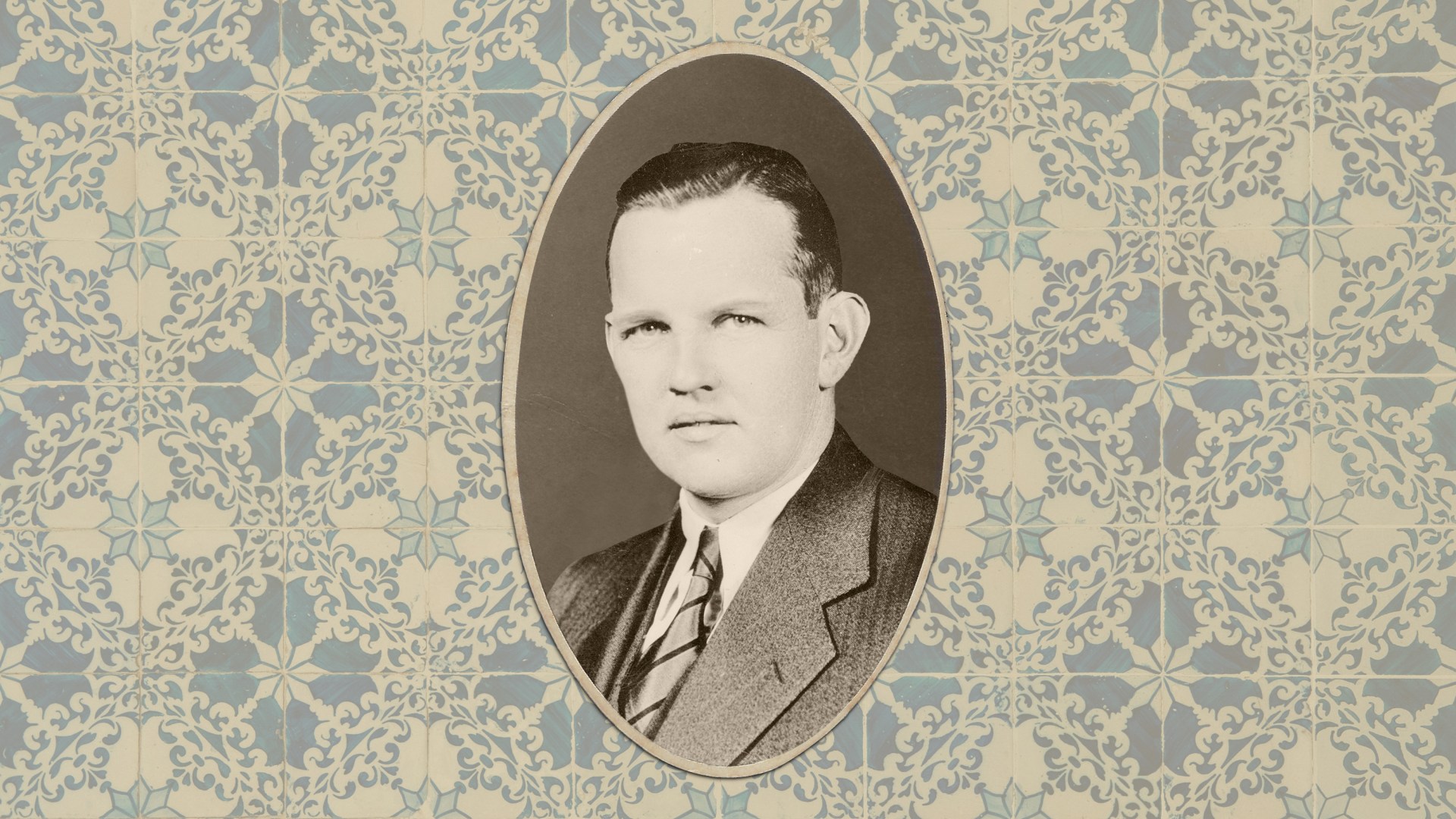

William Alfred Eddy was an American hero. Nicknamed “Bill,” he received the Navy Cross, two Silver Stars, and two Purple Hearts for his service in World War I. During World War II, he quit his job as a college president to reenlist and helped plan the Allied invasion of North Africa. Later, as a diplomat, he advanced Franklin Roosevelt’s agenda by forging the US alliance with Saudi Arabia.

“Eddy (hereafter ‘Bill’) managed to pack four or five lives into a single lifetime,” wrote Princeton University’s alumni magazine about its former doctoral graduate. One of those lives began as a missionary kid to an American family in the Levant.

Part one of this series chronicled the Eddys’ multigenerational service in Lebanon, particularly its southern city of Sidon. Active in evangelism, education, and medical work, some of the Eddys died on the field and are buried in local evangelical cemeteries.

So was Bill. But while his gravestone inscription marks the rank of colonel in the US Marine Corps, it doesn’t include the number of years he “served the Lord” like his family members’ gravestones. The modern Eddy biographer, Muhammad Abu Zaid, didn’t criticize either approach. He called Bill the American “Lawrence of Arabia” and sympathized with his family’s earlier religious commitments.

In Forgotten Pages from the Ancient History of Sidon, published in Arabic by the Baptists of Lebanon, the president of the Sunni Muslim Sharia Law Court in Sidon described the religious and social development of Protestant ministry through building churches, schools, and clinics. Bill, he contrasted, pursued his country’s political objectives in the Arab world.

But today, evangelicals number only one percent of the Lebanese population. And polls indicate America’s poor reputation in the Middle East. Secular or spiritual, how does Abu Zaid evaluate the Eddys’ presence in his homeland?

“I felt sorry for them,” he told CT. “They didn’t succeed.”

The story continues from part one, with William Alfred, age 10, watching his father William King die suddenly on a preaching tour. After this traumatic experience, Bill moved to America and eventually enrolled in a Presbyterian university. Two years later, he transferred to Princeton and graduated in 1917. When the US entered World War I, he enlisted, fought in the tide-turning battle of Belleau Wood, and suffered a leg injury that made him limp for the rest of his life. After receiving his PhD in 1922, he joined the American University in Cairo, and one year later, he became chair of the English department.

Bill remained devout in his Christian faith—he even memorized large parts of the Quran while resisting Muslim efforts to convert him to Islam. In his memoirs, he wrote that he viewed his life as a secular extension of his family’s missionary service. After further academic work at Dartmouth and Hobart College in upstate New York, his military career continued in the US Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA.

But there, he acted in ways he found antithetical to his faith.

Bill’s early espionage helped the Allies turn the tide against the Nazis in North Africa. To destabilize their local authority, he devised a plan to hire French operatives to assassinate local German and Italian agents, shielding the US from public responsibility. And in the Spanish Sahara, he allowed communist rebels to believe that America would facilitate the post-war overthrow of the fascist government on the mainland in Europe—knowing full well the US would not honor this promise. He later compared his deception to Peter denying Jesus.

“We deserve to go to hell when we die,” Bill later wrote.

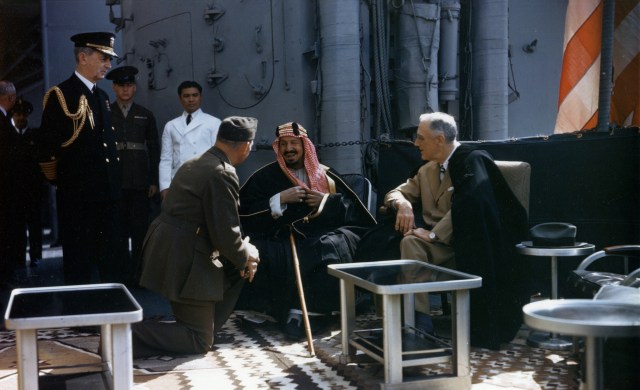

U.S. Army Signal Corps / Wikimedia Commons

U.S. Army Signal Corps / Wikimedia CommonsToward the end of the war, Bill served as head of the US diplomatic mission in Saudi Arabia, where he met King Abdul-Aziz Al Saud. Given Bill’s background in Arabic and knowledge of Islam, the two developed a rapport. On Valentine’s Day, 1945, aboard a naval cruiser in the Suez Canal, Bill served as translator between the king and President Franklin Roosevelt, where the two world leaders bonded over their shared disabilities. The meeting cemented the US-Saudi alliance and displaced Great Britain as the major power in the oil-rich Gulf.

Throughout his career, Bill frequently deployed the cultural acumen and linguistic skills he had first gained as a missionary kid on behalf of American power. He believed US interests aligned well with the Arab world and supported a pipeline from Saudi Arabia to Lebanon that exported oil to Europe. Such infrastructure, he maintained, benefitted every party.

But his analysis did not always square with that of the local populations. In the Gulf, he designed a plan to manipulate opinion in favor of a joint US-Saudi oil venture by feigning Arab authorship of letters to leading politicians. In Lebanon, he strengthened pro-American policies of the Christian president Camille Chamoun that eventually contributed to civil conflict in Beirut.

On the other hand, many Arabs would appreciate Bill’s other diplomatic efforts, even if they ultimately failed. In 1948, US President Harry Truman became the first world leader to recognize the State of Israel. In advance of this decision, Bill resigned from his position and quietly left the State Department as one of Truman’s advisors. He was “embarrassed,” his grandnephew Nick Eddy told CT, having assured Saudi leaders they would be consulted on the matter. Bill later wrote publicly that American support for Zionism would damage its relations with the Arab world.

Toward the end of his life, he settled permanently in Beirut, consulted for oil companies, and even visited Pope Pius XII at the Vatican. Bill died in 1962 at age 66. President John F. Kennedy recognized his “devoted and selfless consecration to the service of mankind.”

Abu Zaid told CT that his respect for Bill and his father, William King, doesn’t hinge on policy. William King served his Lord, as Abu Zaid, a Muslim sheikh, serves Allah. William Alfred served his country, as Abu Zaid, a Muslim judge, serves Lebanon. Both Eddys, he said, were true to their different callings.

Other Middle East analysis is critical. Scholars such as Sayyid Qutb in Egypt, Ali Shariati in Iran, and Abul A’la al-Maududi in Pakistan interpreted both missionary service and diplomatic overtures as meddling within a weakened Islamic world. And Edward Said, a Palestinian Anglican, described them as motivated by Western cultural superiority and in support of its colonialist project.

But many ordinary people appreciate the Eddy missions heritage. The National Evangelical Institute for Girls and Boys, the school they founded in Sidon, has an 1,800-student body. Two-thirds of students are Muslim, including from many of the leading families of the city. Each graduation begins with a message and prayer by a leader in Lebanon’s Presbyterian synod. And last year, the class of 2024 renovated the graves of its missionary founders, whose portraits are hung proudly in the school entryway.

This cemetery sparked Abu Zaid’s book when David Robinson (then the Muslim-Christian relations specialist for World Vision) asked the sheikh’s help to visit the final resting place of his uncle Bill. The scent of lemon blossoms wafted in the springtime air. Who are these Americans buried in my city? the devout judge wondered. His research led him to a remarkable conclusion: Muslims embraced the Eddy family, as they embraced Lebanon.

Turned away by many Arab Christians, William King, the missionary, chose to be buried in Sunni-majority Sidon. Dedicated to an American agenda, William Alfred, the diplomat, desired the same. The sheikh said he believes everyone should be able to preach and serve from their faith, since he claims the freedom to do so for Islam. Muslims may debate the impact of foreign service, but for him, the local mandate is clear.

“I will not advise the missionary,” Abu Zaid said. “But I will do what my religion tells me to do—welcome all and be hospitable.”