Pastor Michael Sbeit stood pensively in front of the marble gravestone in the evangelical cemetery of Sidon, a Lebanese city 25 miles south of Beirut. Mediterranean Cypress trees offered shade from the sweltering summer heat, while their fallen brown needles covered the ground and obscured the inscription engraved in both English and Arabic:

William King Eddy

Born March 13, 1854

Died Nov. 4, 1906

Served the Lord in Syria 28 years

Next to the grave of William King Eddy (hereafter “King”), is the grave of his wife, Elizabeth Nelson Eddy. Her tombstone honors her 49 years of service. Several feet away lies the body of their son, William “Bill” Alfred Eddy, who died in 1962.

The Eddys were an American family who originally came as Protestant missionaries to late 19th-century Lebanon, then part of the Syrian region of the Ottoman Empire. Several family members, including King’s sister Mary Pierson Eddy, and their father William Woodbridge Eddy (hereafter “Woodbridge”) are buried in Beirut.

“They were pioneers of our church,” said Sbeit, who leads the Presbyterian congregation the Eddys’ missionary colleagues founded in Sidon. “We don’t have many like them anymore.”

Two generations of Eddys shared the gospel, built schools, and offered healthcare. The last of their line in Lebanon left a more colorful legacy. William Alfred Eddy’s gravestone notes nothing about service to the Lord and instead displays his rank of colonel in the US Marine Corps.

“Bill loved this city,” said Sbeit. “But he was different.”

This two-part story chronicles the Eddy family’s multigenerational commitment to Lebanon. The family’s modern biographer is Muslim: Sheikh Muhammad Abu Zaid, president of the Sunni Sharia Law Court in Sidon. In Forgotten Pages from the Ancient History of Sidon, he expresses his deep appreciation for their foreign service.

“It is not how we look at the Eddys,” he said. “But how they looked at us.”

Abu Zaid’s sympathetic portrayal of Protestant missionaries contrasts with the more conflicted views that many Lebanese Muslims and Christians have held. Some view them as “sheep stealers” trying to convert the original Catholic, Orthodox, Sunni, Shiite, or Druze populations. Others see them as Western agents advancing America’s political agenda. Still others defend them, citing their years of devoted social service. The Eddys offer evidence each narrative could note.

The family’s story began when Chauncey Eddy, a Presbyterian pastor from New York joined the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions in 1823. But when poor health impeded a potential missionary career, he prayed that God would call his children in his stead. His son Woodbridge and his daughter-in-law Hannah moved to the Levant in 1851, a year after the Ottoman sultan issued a decree to include the Protestant faith among the empire’s legally recognized sects.

The couple’s ministry started in Aleppo by learning Arabic before moving to the Lebanese mountain village of Kfarshima. In 1857, Woodbridge and Hannah moved south to Sidon, where they served in an evangelical church planted two years earlier. They replaced missionary Cornelius van Dyke, who left to complete a translation of Arabic Bible still cherished by many Middle Eastern Christians today.

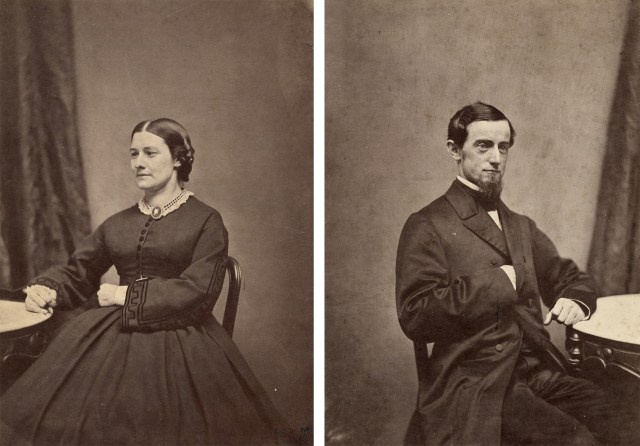

Courtesy of Nick Eddy

Courtesy of Nick EddyChauncey visited his son a year later, delighted at the fulfillment of his prayers. He even preached to the fledgling church, and Woodbridge translated his father’s sermon into Arabic. Over the next two decades, the young couple made their base in the city while continuing van Dyke’s preaching tours in nearby villages. Meanwhile, many of their missionary counterparts set up mission stations in the mountains, populated by Maronite Catholics and heterodox Druze Muslims.

Ottoman authorities neglected education in both urban and rural areas alike. Protestant missionaries prioritized learning not only so people could read the Bible but also to help “civilize” the people. Woodbridge contributed, working alongside local masons to build a school for girls in Sidon that Hannah later administered.

In 1878, Woodbridge returned north to teach theology at the Syrian Protestant College (later, the secular American University in Beirut). By the end of his life, he had written a five-volume commentary in Arabic on the New Testament, which Lebanese Protestants continued to use well into the 20th century. He died in Beirut in 1900, mourned by missionary colleagues and the Arabic pastors he helped train. Hannah died four years later, proud to see three of her five children continue in mission work.

When the Eddy family first came to the region, the feudal society suffered from complex religious rivalries and chaotic colonial interests. As the Ottoman Empire declined, England and France vied for influence among the different sects, which increased the tensions between them.

While many Muslims were unhappy with the colonial powers, they felt neutrally or even positively towards America, which did not play an active political role in the region at that time. Nevertheless, local conflict could still affect mission work. In 1860, for instance, a war between Druze and Christians killed several Catholic missionaries and displaced many American Protestants from their preaching stations.

The schools and medical care that the Eddys and their colleagues offered helped build local relationships. Many missionaries focused their outreach on Muslims and Jews, but as Catholic and Orthodox Christians often profited from their services, church leaders bristled when their members joined Protestant congregations.

Woodbridge’s daughter Mary Pierson Eddy confronted these tensions as a missionary doctor. Born in Sidon and raised in Beirut, at age 22 she suffered a severe fever and nearly died. After she recovered, the experience inspired her to pursue medicine, and she moved to the US to study for several years.

Courtesy of Nick Eddy

Courtesy of Nick EddyIn 1892, Mary traveled to Istanbul, the capital of the Ottoman Empire, and began learning Turkish. The medical committee was confused to see an American woman with perfect Arabic. For the next six hours, she answered their questions and eventually obtained her medical license.

“I am one of you,” Mary told the committee. “I grew up among you.”

After passing the examination, Mary became the first female doctor in Ottoman realms. She spent the next 20 years traveling from Beirut to various villages to treat patients, and in 1904, she opened a center for tuberculosis. Local Maronite clergy grew frustrated at the Protestant presence and eventually compelled her to leave their mountain areas, counseling Christians to avoid her clinics. Mary could not help but notice that sick priests suffering from lung disease still came to her for treatment.

Over time, the physical toll of Mary’s travel threatened her eyesight and ability to walk. In 1916, she went to America seeking care and rest. But as her situation worsened, Mary moved back to Lebanon. She died one year later in Beirut and is buried in the city’s evangelical cemetery.

Mary’s brother William King shared a similar attachment to this part of the world. After graduating from Princeton University in 1875, he took over his father’s ministry in Sidon at age 24 and preached widely in the villages outside of the city. But he also responded to local injustice—brokering land sales in local villages for tenant farmers to free themselves from feudal control.

While his mother Hannah and later his sister Harriet administered the girls’ school, King added a boys’ wing in 1881. Today, the co-ed National Evangelical Institute for Girls and Boys is one of the top schools in Sidon. Missionaries later remarked that their educational efforts brought two schools to every village—their own and the one that Catholics, Orthodox, or Muslims built soon after.

“The Eddys had a vision,” said Sbeit. “Missionaries helped us change.”

In 1906, King was preparing to preach in Alma, a village in northern Palestine, when he felt chest pains. At age 52, missionary colleagues considered him one of the strongest on the team. But now sensing his death, he instructed his Bedouin assistant, who had become a Christian, to secure transportation that could return his body back to Sidon.

After King died, a boat carried his corpse by boat to Tyre. When a storm struck, his friends took the body the rest of the 20-mile journey to Sidon by land. The following day, Muslim, Christian, and Jewish leaders across Lebanon attended a service at the evangelical church. Local shops closed in his honor, lining Sidon’s alleyways for the funeral procession.

Abu Zaid used King’s final words as the opening quote of his book: “Put my body in a coffin and then take me to Sidon. I wish to be buried over there, among the people of which I belong.”

King’s wife Elizabeth returned to America with their two younger children. Both were with their father on that fateful trip and read Psalm 23 to him before he died. After they reached adulthood, Elizabeth returned to Lebanon, passing away in 1931. She was buried beside her husband in Sidon, and her tombstone notes 49 years of service to the Lord.

The younger child, William “Bill” Alfred Eddy, was 10 years old when he watched his father die. He eventually took a path of his own, and his story will be told next in part two.