More than 30 women and children sit on plastic chairs under the awning at Goro Medical Center (GMC), a clinic in rural northern Uganda. Some nurse infants. Others stare into the distance as their immune systems fight high fevers.

As the sun moves overhead, a baby shrieks. The other patients wait silently for Orach Simon, a lab technician, to test their blood for malaria, syphilis, or hepatitis. Orach and the other lab tech, Atimango Mercy, often stay late. They have both come in to work while sick with malaria.

Patients enter the clinic, walk behind a blue sheet, sit on a green plastic chair, and offer Orach their ring finger. He logs each test result in a large red book that lies open on the adjacent counter, beneath a 2024 calendar that he uses for 2025.

Orach longs for air conditioning. It’s often over 100 degrees Fahrenheit, and temperatures over 95 can destroy test kits. As he serves his long stream of patients, Orach wrestles with what it takes to keep GMC’s doors open—and to support his wife, one-year-old daughter, parents, and younger siblings.

Last September, government registration challenges closed the clinic, but it reopened late last year. Now Ugandans who frequented government-funded health centers once supported by $270 million in US funding are coming to GMC. For years, many of the 1.4 million Ugandans who are HIV-positive received antiretroviral treatment and basic health care at government-run health centers. Now, many come to the clinic when they’re sick, and GMC has tripled the amount it spends on drugs.

GMC sits in Nwoya District, a swath of farmland and bush covering roughly 1,800 square miles, larger than the state of Rhode Island and home to more than 220,000 people as of the 2024 census. Anaka Hospital and three government-run health care centers serve the whole community. Health care centers like GMC provide outpatient, inpatient, maternity, and lab services.

Few patients can see physicians. Each health care center has a clinician, such as a nurse of clinical officer, who serves as a de facto doctor. Meanwhile, Anaka has struggled to hire and retain staff. In 2019, the Daily Monitor reported Anaka operating with less than half the expected staff and no specialists. In July, Anaka handled 10,000–14,000 outpatients monthly while struggling with hazardous-waste removal after USAID exited.

Gulu, a city 30 miles away, has three hospitals. But few people have money to pay for a boda-boda (motorbike) ride to the city, making its medical services largely unreachable for locals.

Orach, 30, was born in Pader, a district to the east of Gulu, in the mid-1990s, at the height of Acholi warlord Joseph Kony’s violent assault on his own people. Though Kony claimed the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) fought on behalf of the Acholi people’s interests, the witchcraft-obsessed militant and his army regularly kidnapped children from across northern Uganda and forced them to commit atrocities. Orach walked several miles from home each night to hide from the LRA.

After the LRA kidnapped two of Orach’s cousins, he and his family fled to a camp for internally displaced people in the south.

“You were tired, but if you wanted to rest, they would kill you,” he said, remembering the journey.

In the camp, ten-year-old Orach visited an aunt with tuberculosis. He wept and decided to become a doctor. His parents, subsistence farmers, saved what they could to send him to school. But the money only went so far. Orach couldn’t afford medical school, so he trained as a lab technician instead: “I became stressed, disappointed, and sad, but I managed to cool down using Bible verses and advice from a close friend. A problem shared is a problem solved.”

In 2019, Orach graduated and accepted a job as a lab tech in South Sudan, eager to help support his family. His employer paid for a car to drive him to Jonglei State, about 300 miles north of Gulu. But once Orach got there, “I suffered.”

Jonglei, plagued by conflict since South Sudan gained its independence in 2011, restricted Orach’s freedom. Rebel checkpoints choked travel. Immigration authorities demanded monthly bribes to let him stay in the country. His boss, though kind, did not always pay him. Orach cried every night, grieved by how little he could send home.

Raised Catholic, Orach joined a Pentecostal church that became his lifeline. Church members prayed for him, taught him Arabic, and welcomed him like family. “Their love touched me,” he said. But fear was constant. Once, he saw a gunman shoot a Ugandan vendor dead after a petty dispute over soap. “My life could end like that,” he realized.

In 2022, he finally left. On the drive toward the Ugandan border, he passed bodies still lying in the road after an ambush. At the crossing, police took the little money he had left. He stepped onto home soil broke but alive.

The next year, Orach found his way back to a microscope in Nwoya, working for GMC. Although the clinic would never make him a doctor, it could make him essential to people with no doctors.

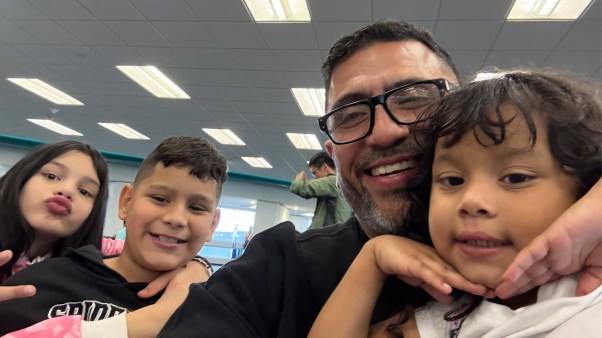

Thomas Charities, a ministry focused on treating those suffering from malaria, opened the 12-bed clinic that year. Orach started working there in 2023 and said he feels joy when a diagnosis helps his patients. Most nights he sleeps in a grass-thatched hut about a ten-minute walk from the clinic and attends St. Luke’s Church.

Once or twice a month, he pays for the six-hour boda-boda ride back to see his wife and son. Other weeks, he goes to visit his parents, who live a similar distance away. His dad is too old to farm now, and his mother is sick. He also sends money to them: “I pray that God finds ways for me to take care of my family better.”

And he talks to God about his hopes for health care in the area: “People are suffering.”