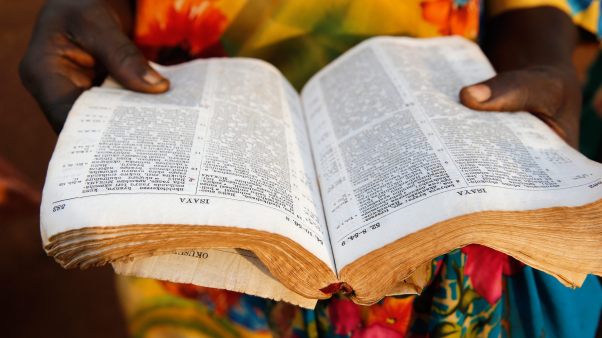

Armed Boko Haram militants kidnapped Murna Yusuf, then in her early 30s, in July 2021 as she rode on a bus from Kukar-Gadu, Yobe State, to Maiduguri, Borno State, in northeastern Nigeria. The terrorists found Yusuf’s worn Bible as they rifled through the passengers’ belongings.

“They asked if I was a Christian,” she said. “I was not going to deny Jesus for anything—not even for Boko Haram.”

The militants threw her Bible back to her, ordering her to pick it up. Then they separated her from the other passengers, most of whom were Muslims.

“I begged them to let me go, but they said only if I change my faith,” she said. “I thought that was the end of me. All I could pray for was God’s mercy.”

The militants drove her more than six hours into the deepest part of the forest, then put her in a house with two other captives—Agnes and Christy—who soon became her friends. They ate sparse meals of ground guinea corn mixed with wild leaves gathered from the bush. Yusuf and her two companions fetched water from streams, gathered firewood under watchful eyes, and clung to their faith in secret. “We read from my Bible, fasted, and prayed for several days,” she said. “On Sundays, we held quiet services, singing praises in our hearts so they wouldn’t hear.”

For five weeks, Yusuf endured her captors’ attempts to coerce her into converting to Islam. Then Yusuf and her friends sneaked out of the camp. They set a pot on fire as a distraction and pretended to run for water from a nearby stream. They didn’t come back, instead trekking through the night. During the day, they evaded Boko Haram patrols by hiding in the tall grass. A suspicious boy nearly alerted the insurgents, but the women were able to get away.

For six days, they walked without food until they arrived at a road between Sabon Gari and Damboa in Borno State. They flagged down a car, hid in the trunk, and eventually reached Agnes’s uncle’s house in Biu.

“We lay on the floor, too weak to move,” she said. “But we knew that God had delivered us.”

Her suffering didn’t end with safety. More than four years later, Yusuf still struggles with panic attacks, insomnia, and flashbacks.

In Nigeria’s northeast, hundreds of women and girls like Yusuf have escaped Boko Haram’s brutal captivity only to face ongoing trauma as they struggle to reintegrate into their families and communities. They face mistreatment and stigma, in a region that lacks resources to treat trauma. Since 2014, the Islamic militant group has abducted at least 1,500 children, as well as women.

Boko Haram opposes education for women and often targets young women and girls in schools. In 2014, Boko Haram kidnapped 276 schoolgirls from Government Girls Secondary School in Chibok in Borno State. Four years later, they abducted another 110 preteen and teenaged girls from a school in neighboring Yobe State. Some remain captive, including 82 Chibok girls. Militants have held Leah Sharibu, a Christian who refused to convert to Islam, for more than seven years.

Survivors recount beatings, sexual violence, and assault. Militants indoctrinate their victims and force them into marriages and domestic servitude using torture, psychological abuse, and coerced religious conversion. The terrorist group sells some victims into sex slavery or uses them in suicide bombings.

Nigerian military efforts and negotiations have led to the release of some kidnapped girls. Others have escaped—jumping from moving vehicles, fleeing during chaos, or sneaking away after weeks or months in the camps. Thousands of survivors have said their escapes were followed by further violations by Nigerian military, including starvation, rape, and forced abortions.

“Instead of receiving protection from the authorities, women and girls have been forced to succumb to rape in order to avoid starvation or hunger,” Amnesty International said. The Nigerian military denied the allegation.

Even after escaping, the threat of retaliation from Boko Haram members lingers. Fear dominates survivors’ daily existence. Continued attacks make some villages dangerous for aid workers to reach as they try to help escaped victims.

Yusuf said stigma also discourages survivors from seeking help. Communities shun survivors as tainted, believing they are radicalized or in collaboration with their captors.

“It’s not just the memories,” Yusuf said. “It’s also how people treat you.”

For her, rejection came from fellow Christians. Yusuf said some church members mocked her: “I felt like it was my own people hurting me.”

Stigma also makes finding a spouse difficult. Some have returned from captivity with children born of rape. Communities often reject them and their children. One survivor told the BBC she sometimes wished she was back in the forest instead of suffering under the stigma of having been a Boko Haram bride.

Veronica Kaduwa, who spent more than three years in Boko Haram captivity before escaping, told CT, “The mockery and assault isn’t worth it. Sometimes it feels worse than when you were in captivity. I wish churches were doing more to help us.”

While some churches are stepping up assistance for survivors, access to counseling and to humanitarian aid workers providing drugs, food, and shelter remain limited.

“Several girls showed signs of stress when talking about their experiences,” Mausi Segun, a Nigerian human rights researcher, told Human Rights Watch. “The girls said that their fathers tried to counsel them, or that their pastors told them to pray. But they needed more.”

Local and international Christian organizations try to fill in the missing pieces. Open Doors International’s trauma program holds weeklong seminars with teaching and counseling for survivors and offers ongoing trauma care through local coordinators. In September, the Gideon and Funmi Para-Mallam Peace Foundation hosted a trauma-care event, with mentoring by women from four local churches. Eleven survivors participated.

Founder Gideon Para-Mallam said the foundation launched the program and introduced longer-term counseling services after recognizing the psychological toll—panic attacks, chronic insomnia, high blood pressure, and flashbacks—that survivors continue to experience: “Many of them have struggled to get on with life.”

“Churches must go beyond thanksgiving services [when the girls are out of captivity],” Para-Mallam said. “Society has moved on, but God calls some of us to keep their plight in public view.”

Yusuf currently attends Christian support groups to help cope with her trauma and hopes to channel her pain for a bigger purpose.

She enrolled in a master’s degree program in counseling at the University of Abuja in Nigeria’s capital and provides guidance to other survivors.

“God has sent two girls my way,” Yusuf said. “They went through hell. So I use what God has deposited in me to encourage them.”