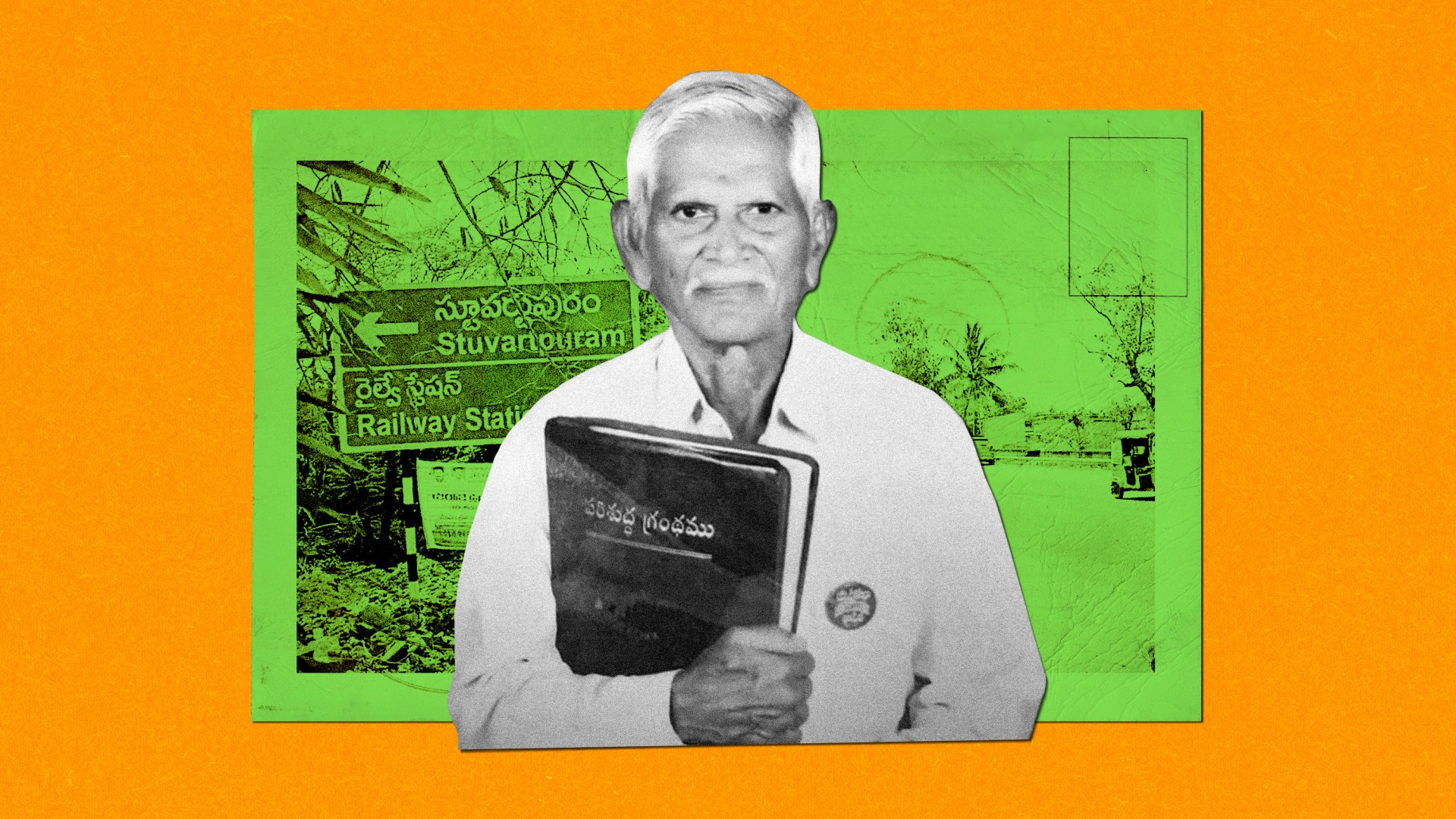

Over the past four decades, octogenarian Bollaku Issak has preached hundreds of sermons. The diminutive pastor with white hair and a knock-kneed gait ends each service with the same altar call.

“If God can save a wretched sinner like me, he will definitely save you,” he says, his voice softening. “You are no different. You are loved. Just surrender. Repent and be saved.”

Often as he utters those words, tears well up in his eyes, transporting him to his life before Christ. He once lived as an armed robber, or dacoit, in Stuartpuram, an infamous village in Andhra Pradesh considered a “reformatory colony” by the British colonial government. Families lived off banditry for generations and passed it on to their children as an inheritance. In the aftermath of any major theft in the region, police invariably suspected Stuartpuram gangs.

Bollaku himself led a band of nine men, breaking into houses, trains, banks, and government offices, he recalled in a recorded testimony. He earned the moniker Bangaru Pichchuka(“Golden Sparrow”) for absconding with gold worth millions of rupees and for going on thrilling escapades. Yet years of living in hiding to escape the police robbed him of peace. Every time he tried to go straight, he slipped back into banditry with greater force. Weighed down by criminal life, he even tried to chop off his own arms, he said.

To evade arrest and charges, Bollaku bribed the police. Authorities finally outwitted him after four decades, booking him under charges amounting to seven years of imprisonment. His numerous attempts at jailbreak proved unsuccessful. The thought of spending seven years inside the fortified walls of prison, away from his children, left him feeling hopeless.

In prison, a fellow convict who had recently became a Christian explained the gospel to Bollaku. Hearing about the love of Christ and the promise of salvation reinvigorated his spirit. Over the next two months, he prayed, sobbed, repented of his sins, and learned about the Bible. He prayed persistently that somehow his prison term would be shortened to a year.

“It was a miracle!” he said in the testimony about the trial. “The prosecution could not gather evidence. The court struck down the charges against me. I was completely set free.”

After walking out of prison, he spent the next 14 years serving as a volunteer at a local church—sweeping floors, cooking, and cleaning dishes. As a spiritual life of prayer and service took root, he never returned to his old ways. One morning as he prayed, Bollaku had a vision: Jesus laid hands on him, instructing him to testify about the Good News that had turned his life around. Since then, Bollaku has sought to follow this calling.

Bollaku’s testimony is not uncommon in Stuartpuram, which in the past four decades has seen a revival as nearly all its 5,000 residents have become Christians. The “Village of Dacoits” has become Suvarthapuram, Telugu for “Gospel Village.”

“People here live out Christianity, be it in personal or professional lives,” Bollaku told CT. “God has become the center of our pursuits today. This was unheard of a generation back.”

About 20 churches dot the lanes and alleys of the village. The days of police officers descending on the village after every major theft are long over.

Today, Stuartpuram is known for its accomplishments rather than its crimes. The village has produced two weightlifting gold medalists, as well as doctors, engineers, teachers, lawyers, civil servants, government ministers, and even a state police chief. Villagers owe it to Salvation Army missionaries for laying the groundwork for lasting change.

The British initially founded Stuartpuram in 1913 as a “reformatory colony” under the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871. The act designated certain nomadic and seminomadic tribes as “born criminals” who made a living through banditry. The Yerukulas, a gypsy community that resides in Stuartpuram, were branded as a criminal tribe. Colonial authorities visited prisons to identify Yeruluka convicts and settle them in the newly formed village. The village is named after Harold Stuart, a British civil servant who pioneered the model of resettlement colonies.

Later research revealed that equating ancestry with criminality was solely based on colonial prejudice. Yerukulas originally traded salt and grain, riding donkeys to different villages to earn a living. They made and sold brooms, mats, and baskets to supplement their income. The introduction of railway transport in the 1850s replaced traditional traders, including the Yerukulas. Then the enactment of the Indian Forest Act of 1878 cut them off from the forests where they sourced materials for their handicrafts. Illiterate, landless, and scorned by the upper caste, many of them felt they had no choice but to turn to crime.

After moving to Stuartpuram, many continued to live as bandits. In 1913, Stuart decided to turn to the Salvation Army, which had already gained a reputation for transforming criminals. Frederick Booth-Tucker, Salvation Army’s special commissioner for India and Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), wrote at the time, “The Gospel remedy has lost none of its ancient power when applied by those who have themselves experienced its revolutionizing and soul-reforming influence.”

Under the Salvation Army, life in the settlement was restricted. Leaders required roll call for all the residents, day and night, and banned villagers from venturing out of Stuartpuram. They established an elementary school where children learned about Bible stories and moral education, and they provided adults with employment opportunities like cultivating land or working at the Indian Leaf Tobacco Development Company Limited (ITC Limited) in nearby Guntur.

After India’s independence from the British in 1947, homegrown movements such as Laymen’s Evangelical Fellowship and the secular nonprofit Samskar Organisation continued this work, driving change through education, job opportunities, and moral reform.

Yet the stigma around Stuartpuram remained. Popular Telugu historical dramas bearing the name Stuartpuram cemented the image of its residents as dacoits. In Christian circles, however, testimonies of transformed lives began to alter the popular perception. For instance, Abba Khan Yesudas was a dreaded dacoit for 45 years. While doing time in Madras Central Prison, he—like Bollaku—heard the gospel from a fellow inmate. After his release, he became an evangelist. Another well-known figure is Christian songwriter Stuartpuram Sudhakar, whose popular Telugu songs capture his criminal past as a bandit and the new life he found in Christ.

Today, the Christians of Stuartpuram are sharing the gospel with neighboring villages. The village hosts annual gospel conventions that draw about 2,000 people from nearby towns such as Guntur, Bapatla, and Chirala, as well as distant cities like Hyderabad and Chennai. Six young people from the village recently translated the New Testament into the Yerukula language, aiming to distribute it to Yerukula communities across India, according to Chukka Paul Raju, president of Stuartpuram Grama Abhivrudhi Mariyu Sankshema Samithi, a community organization advocating for the village.

Residents have asked authorities to officially change their village’s name to Suvarthapuram to shed their reputation from the past, Raju said.

“We are no more Stuartpuram and whatever it represents,” Raju said. “Suvarthapuram alone captures the transformation that Christ has brought into this place.”