Here in the rural heart of Burundi, there is a red dirt route that serves as a 5k walk for me. Down the hill, across a small stream, then keep going until you turn left at the cemetery. Due to its proximity to the hospital where I work as a family medicine missionary physician, this cemetery has expanded greatly in the years I’ve lived here. It is mostly a collection of bare wooden crosses scattered in the shade of fast-growing eucalyptus trees.

But halfway through the cemetery, there is a small clearing. Here the graves are prominent, with large, white-painted crosses that give names and dates of births and of deaths. The graves are covered with tile, sometimes flowers. These are mostly people I’ve known. I was present for most of the burials. They were colleagues and friends at the hospital. Most were my patients before they died.

I pause in my walks and remember these people and their deaths. Josué was our cashier, wheelchair-bound since before I met him from some old injury. He was smart and kind and unfortunately couldn’t feel the infection in his legs until it had overwhelmed him.

Silas was a pastor, gentler than anyone could expect from the years he lived as a refugee in Tanzania. He was sick for years, and though I had a suspicion of his diagnosis, I had neither the tests to verify nor a treatment to help him.

Justine had something wrong with her liver, but I wasn’t able to find out what exactly, and her sudden decline surprised me.

Jean Philippe’s sudden death remains a mystery to me to this day.

They were young. None of them near what I might consider retirement age. Pondering the graves around me, I am confronted again and again with the fact of death. Death has come and taken them from us. When might it come for me?

The more precise question, medically speaking, is what disease is likely to kill me. Accidents and other tragedies aside, disease is generally how we die.

Recently, my son was doing a school report on author J.R.R. Tolkien, and he wrote that Tolkien died “from old age.” My doctor reflex automatically kicked in: “No one dies from old age,” I told him. Though the phrase is widely used, any doctor will tell you that there’s always some underlying illness. In Tolkien’s case, it was a bleeding ulcer, but dying “of old age” usually means that the person was old and their doctor did not have an exact diagnosis. This is why we don’t write “old age” as a cause of death on a death certificate. Death comes by disease, even if we have not found it.

Of course, disease does not always lead to death. A child’s fever doesn’t threaten her life in wealthy countries (though it may in Burundi). Many chronic diseases can be managed for years before they bring the possibility of death—if they ever do.

That ability to separate disease and death surely contributes to the focus of American doctors and patients alike on disease rather than death. But this focus, though medically intelligible, is spiritually impoverishing. The Bible, church history, and Christians in poor countries today all pay more attention to death, and that attention offers insights that can help us live more faithfully in our mortal lives.

Westerners have not always thought about disease and death as we do now. In the art and literature of other eras, we often see death personified. Though people in the past knew full well that disease could lead to death, they spoke of Death, rather than disease, coming to find us. He could be avoided for a time, but not forever. Disease was merely his agent; Death was the real fact, with power over all, great and small alike.

This tradition has faded from both medical and popular mindsets, especially in wealthy countries. Advances in accessing medical care mean that, in high-resource settings, we almost always know which disease was the immediate cause of a person’s death. We now view disease as the real fact of the situation and death as merely its occasional consequence.

I was trained as a physician in this newer way of thinking, but that mindset could not survive my work abroad. For years now, I have tried to treat patients in desperate circumstances. Their diseases often remain obscure to me, but the coming of death is clear. Living in this more traditional paradigm has forced me to rethink the relationship between death and disease. It has sent me searching out what Christianity has to say of these two great inevitabilities.

The Bible speaks broadly and with great nuance about disease. It is a result of sin in the world, but not necessarily the direct result of sin in the diseased person (John 9:1-3). God sometimes sends disease (2 Sam 24:15), but he also heals and calls his people to do the same (Luke 9:1-2). Healing was central to Jesus’s ministry, and it proclaims what God’s kingdom is like (Luke 7:18-23). Nevertheless, we see a persistence of disease even in Jesus’s followers (1 Timothy 5:23) that speaks of a kingdom still to be fully realized.

Because disease is fundamentally suffering (or at least the threat of suffering) in a person’s mind or body, disease can be understood much as we understand all suffering: as something that is fallen but not without redemption (Gen 50:20, 2 Cor 12:9). We tirelessly fight disease as a result of the Fall. But when it persists despite our efforts, we seek to be faithful in that suffering, trusting that God can and will redeem it in ways that we may only barely understand.

The Bible also speaks of the obvious ways in which disease leads to death (e.g., Psalm 107:18). Yet Scripture also understands death as more than an endpoint of disease; its model is closer to the older tradition than the modern framework.

In Genesis 3’s story of the Fall of humankind, the consequence is not disease but death: “you will die” and “to dust you will return” (vv. 3, 19), though disease will be death’s tool. Jesus healed, but his life was directed toward death—and resurrection. Paul personifies Death in 1 Corinthians 15 using the words of Hosea to address Death directly—“Where, O death, is your sting”—and describing it as the last enemy Christ destroys (vv. 26, 55).

Like disease, death was never natural in the sense of being part of God’s original creation. And like disease, it will cease in the fullness of God’s new creation. But unlike disease, since Christ’s resurrection, death is more than a defeated enemy: Until Christ returns, it is how we see God face to face (1 Cor. 13:12). In that sense, to “live is Christ,” as Paul writes, but “to die is gain” (Phil. 1:21).

Christ our Lord has walked this path before us. Now, as poet Malcolm Guite writes, God’s grace is “pulling us through the grave and gate of death” into the fullness of his presence.

These biblical passages should shape our understanding of disease and death at least as much as modern medicine does. Let’s take disease first. There’s no doubt that the kingdom of God advances against disease, and part of Christ’s destruction of the works of the devil is our fight against disease (1 John 3:8, Matt 11:4-5). Medicine, surgery, public health initiatives, sanitation, lifestyle modification—all these can be weapons of God’s people for God’s purposes. It is a glorious thing when disease is vanquished.

Yet we must remember that health and length of days are primarily an opportunity to love and serve God and neighbor (Matt 22:36-40). Health is good, but it is not an end unto itself. And when sickness is not vanquished, despite our best efforts, we must love and serve then too. In this, persistent disease and suffering may not always or only be an obstacle: Suffering can build compassion. Disease can force us to slow down to what John Swinton calls “the speed of love.”

As for death, Christians look for its coming, difficult though that may be. A 2019 study in the Annals of Palliative Medicine reported the results of a survey of hundreds of people asking their preferred way to die. Overwhelmingly, respondents wanted to live a long, rich life and then die in their sleep.

Why is this idea so appealing? The study suggests a variety of reasons, but I think most come down to a preference for living as if death is not waiting for us.

Here in Burundi, death is common and sudden, including among the young. Funerals are attended by the hundreds, and I expect few reach adulthood without having sung in a funeral choir. Nevertheless, I find here much the same sentiment about death that I find in America—the same avoidance those researchers found. Even here, where the subject is unavoidable, talking about death is met with the same hesitation. Even among many Christians, I find the same futile wish to spend life ignoring its most inevitable event.

Yet there are exceptions to that rule. Pastor Silas, one of my friends in the cemetery, came to talk to me in the final stages of his unknown illness. He wanted to go visit his friends in Tanzania. They were meeting to pray, and he wanted to take a long public bus ride on a broken road to join them, even in his frailty.

He knew the trip would take a toll on his body. He knew death was near and that this journey would bring it nearer, but still he wanted to go. He made that trip and got back home again, and though we didn’t talk about it directly, he showed me how life is more than length of days.

The difference between how Silas faced death and how many of my other patients do—and the lack of difference between their attitudes and those of my American friends—tells me our approach to death is not determined by our circumstances. Whether death is sanitized and hidden away as in much of America, or raw and ever-present as in rural Africa, we must decide how we will approach it.

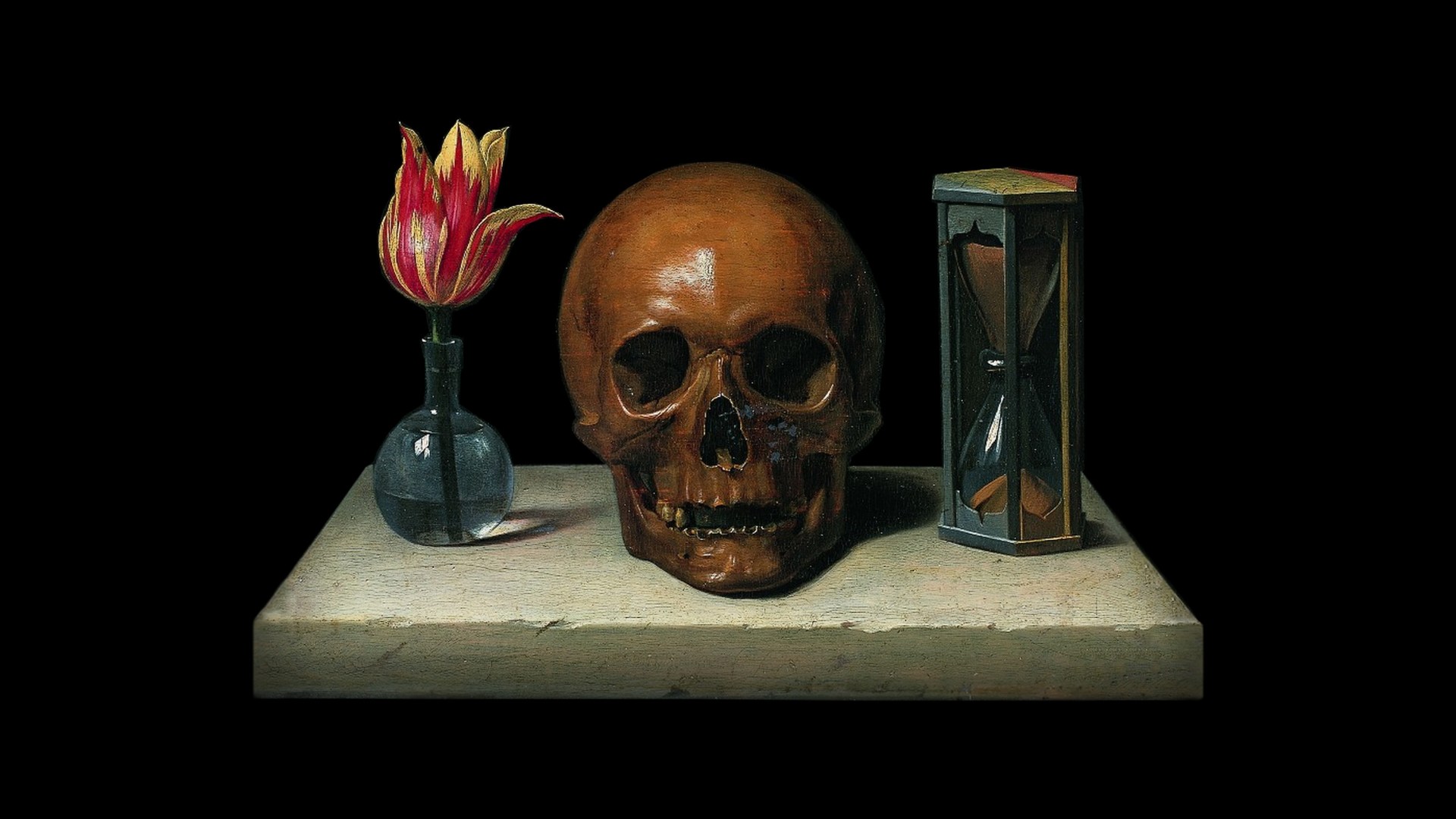

For centuries, many Christians carried on the tradition of memento mori, the Latin reminder that we will all die. They would engrave a skull or some other symbol of physical mortality to regularly confront themselves with the fact of death and the need to prepare to meet it. Perhaps these Christian forebears would endorse my habit of taking a regular constitutional past the graves of my friends.

Here I find myself wanting to suggest that Christians should be marked by having no fear of death, but perhaps this is not reasonable. Even defeated, death marks such a transition—such an unknown—that fear seems inevitable.

What matters, I think, is less the absence of fear but the presence of hope. Is our faith in Christ’s promise of resurrection more than lip service? We don’t know much about the other side of that door, but if Christ is raised, then life is there (1 Cor. 15:12-28). Life in the presence of our Savior.

Lastly, what of the intersection of disease and death? Not every disease will end in death, but most lives will end with disease. Medical rescue from death is glorious and redemptive—but always temporary. There is a moment in every treatment where we, doctor and patient alike, must shift our efforts from fighting disease to facing death well. Knowing when that shift should take place is always hard, but cultivating this presence of Christian hope in death may be the best way to protect against compulsively fighting disease and losing the bigger picture.

A “good death” is about more than chronology, more than the prolonging of life by medical or other means. We will only meet death well when we understand that life is more than length of days, and there are worse things than losing years. When I pass the graves of my friends, I remember their diseases but, more than that, the hope they have realized. Awash in that hope is how I hope to die.

Eric McLaughlin is a missionary doctor in Burundi and the author of Promises in the Dark: Walking with Those in Need Without Losing Heart.