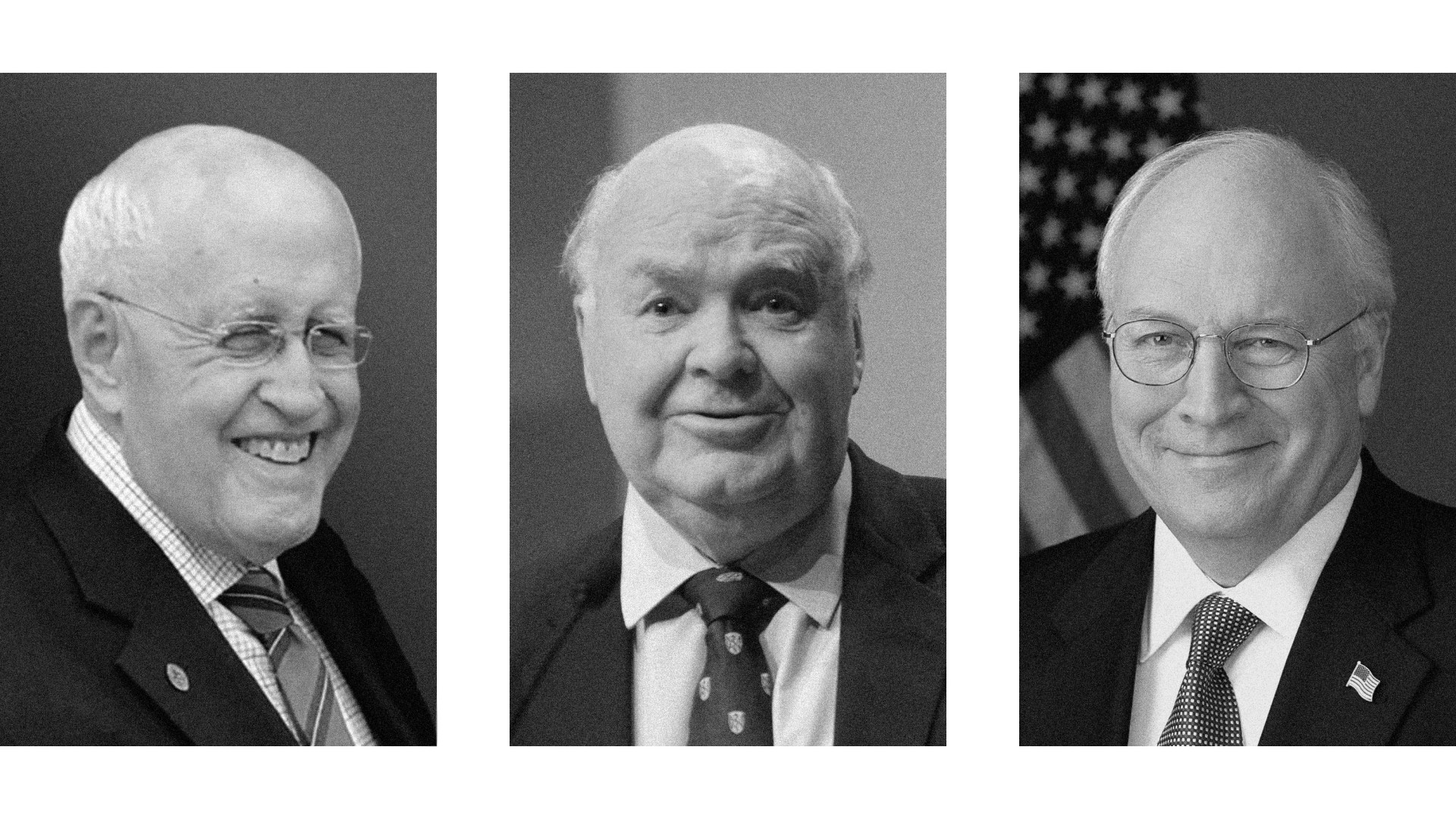

In “Man Knows Not His Time,” Puritan Increase Mather preached in wintry 1696 Boston about the surprise of unexpected dying. Many of us do not know our own times regarding the surprises of unexpected social and political changes. These three men, ages 83, 84, and 82, reacted vigorously to those changes: recently deceased syndicated columnist William (“Bill”) Murchison and Vice President Dick Cheney and still-living Oxford professor John Lennox.

Those who attended Murchison’s October 27 memorial service in Dallas learned he was born in 1942 and graduated from the University of Texas in 1963. He had 60 years as a faith-filled journalist and 50 years as a faithful husband. On CSPAN in 1999, Murchison said, “As a political commentator, it is my conviction that a marriage, a good marriage, is a happier event than an election.”

The service was held at Episcopal Church of the Incarnation, where Murchison was a chalice bearer for 47 years and a vestryman for multiple terms. But he was an Episcopalian with a difference. In his 2009 book Mortal Follies: Episcopalians and the Crisis of Mainline Christianity, Murchison wrote sardonically that “the God you increasingly hear spoken of in Episcopal circles is infinitely tolerant and given to sudden changes of mind” and is “a God that the culture would be proud of, as against a culture that God would be proud of.”

Murchison ardently opposed abortion and supported sexual distinctions: The summer 2025 issue of The Human Life Review, which he helped edit, lists on its cover a Murchison article headlined, “There Are Boys; There Are Girls.” Murchison and I corresponded over the years, and I interviewed him in front of Patrick Henry College students in November 2013. My first question was how journalism had changed during our half century within it. Here’s what he said:

Most journalists had the commitment that whatever they worked for—magazines, newspapers, TV stations—they were not your brains. They were your eyes and your ears. They existed to tell you how to use your own eyes and ears. That came to a sad end in the post-Watergate period when journalism began to reinvent itself as the kind of alternative source of wisdom, competing with colleges and universities and churches in terms of announcing what was important and what needed to be thought about and what we ought to think about it.

Murchison added that the older journalism came out of “people who had not been to Harvard, Yale, even Patrick Henry College.” He continued,

They joined newspapers because they loved to be on the frontlines of events. They loved to tell stories. … They loved to answer questions: What’s all this about? What’s really going on? Why should we care about it? They loved to answer those kinds of questions rather than to pose the question that journalists are fond of posing today: Why don’t you agree with liberal intellectuals?

Murchison, along with reporting for and editing the Dallas Morning News, wrote The Cost of Liberty: The Life of John Dickinson, a biography of the man known as the “Penman of the Revolution” for his highly influential Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania (1768). Dickinson, Murchison said, “wrote in favor of what he called ‘balanced moderation,’ the idea that a thorough and wholesome discussion is necessary before extraordinary actions are taken.”

Murchison in 2013 said that if 21st-century progressives had not demanded such a rapid increase in what they saw as progress, “the level of anger would not have risen.” He added, “We need more people like Dickinson, instead of fewer. The lack of forethought and caution almost makes inevitable the rise of hotheads.”

But Murchison also wanted conservatives “to take prudent action” and said that “Dickinson did not consider burning down the barn to exterminate the vermin to be prudent action, but rather an action with more dire consequences than not.”

Dick Cheney, who died Monday, November 3, at age 84, grew into prudence. He went to Yale University to play football but flunked out twice and had a drunk-driving conviction in 1963 that he said was a turning point in his life. He graduated from the University of Wyoming, had six terms in the Congress, and was secretary of defense and then George W. Bush’s vice president from 2001 to 2009.

I met Cheney only once and know little about his religious life or lack thereof, and obituaries haven’t provided many details. When asked about his beliefs in Clio, Michigan, in 2004, he said, “Well, I—my family was serious about their faith. My mother sang in the church choir. Dad was the church treasurer, as was his father before him. I grew up as a Methodist. And it has been an important part of my life, and our family’s life.”

Cheney then quickly pivoted:

But it’s also important to remember that one of our great strengths as a nation, one of the great gifts we have as Americans is freedom of religion that, in fact, we do believe in the separation of church and state. … I think it’s perfectly appropriate for us to recognize a divine being in the course of affairs of this nation, as did the Founding Fathers. … Our religious faith and religious convictions played a very important role in the founding of the country. I think it’s very important to a great many Americans.

Not a profession of faith that excites me or probably many CT readers. Nevertheless, while I disagreed with him about some things, in our current context I’m impressed that he had no personal scandals in decades of governmental service and no marital scandals during 61 years of devotion to his wife, Lynne, until death parted them. It takes all kinds of people to keep a ship going, and Cheney did speak of “the fixed stars by which the American ship of state navigates … our belief in limited government, in democracy, in pluralism and the rule of law.”

Steve Hayes, CEO of The Dispatch and a close observer of Cheney’s vice presidency, said on The Bulletin last week that Cheney was private about matters of faith:

That carried over to the way that he addressed issues that we would all deem as important to social conservatives. They moved from the kinds of issues that he was most comfortable with—national security issues, economic issues—into what I think he would describe as softer issues and issues that had more to do with feelings and faith than he was comfortable discussing in public.

Mike Cosper on The Bulletin added, “Late in his life when he stood with his daughter Liz when she bucked the entire party, those were remarkable moments. They were moments of courage.” Russell Moore recalled, “That moment in the 2004 vice presidential debate, when he said to the Democratic nominee John Edwards, I’m at the Senate every Tuesday, presiding over the Senate as vice president. The first time I’ve ever met you is now—behind it was this sense of responsibility. The contrast was just amazing.”

Cheney’s colleagues applauded, sometimes sardonically, his honesty. George W. Bush White House hand Dan Bartlett said in a Miller Center oral history series that he and others knew where they stood with Cheney: “In Washington and politics you get a lot of people who will stab you in the back. Dick Cheney was perfectly comfortable with stabbing you in the chest.”

On to Irish-born John Lennox, who turned 82 on November 7. As a student at the University of Cambridge, Lennox attended the last lectures of C. S. Lewis in 1962 and graduated from that institution with a science PhD in 1970. He then taught about science and religion at the University of Oxford and over the years had debates with Christopher Hitchens, Richard Dawkins, Peter Singer, and others. Lennox is the author of many books, including God’s Undertaker: Has Science Buried God? and Seven Days That Divide the World: The Beginning According to Genesis and Science.

Lennox sees the importance of speaking out, as Murchison and Cheney did. When I interviewed Lennox in front of Patrick Henry College students in 2012, he spoke to them about not hiding their light:

I’ve had bright graduate students saying, “We’re doing biology, and if we were to even suggest that we have a very dimensional Christian faith, we’d be looked at negatively, so we have to be very careful.” I would agree with that, but I think silence cannot be the answer, because in my experience people who say, “I’ll wait until I get tenure” or “I’ll wait until I become CEO,” et cetera—it never happens.

Lennox continued,

When I was 19 at Cambridge I met my first Nobel Prize winner. I sat by him at dinner and didn’t keep quiet about my Christian faith. I tried to talk to him about God and wasn’t very successful. At the end of the meal, he insisted I come to his room for a cup of coffee. He invited three other full professors and just me. He sat me down and said, “Do you want a career in science?” I said, “Yes, sir.” He said, “Give up this childish stuff.” The pressure was colossal. I managed to screw up enough courage to say, “What have you got to offer me? If it’s better than what I’ve got …” He came out with some evolutionism. I said, “If that’s all you have to offer me, I’m going to take the risk.” He was furious, but somehow it put steel into my heart.

Lennox’s bottom line is from the beginning of the Gospel of John. To the students he quoted, “‘In the beginning was the Word.’ That is of profound importance. This is a Word-based universe. In Genesis 1, God, who of course could have done everything at once, did it in sequence. He spoke. Then he spoke again. And he spoke again.”

Lennox said God created the world in six days, but Lennox did not stipulate that “they are 24-hour days within a single earth week.” He went on to tell stories about the departure from teaching of C. S. Lewis, who died on November 22, 1963, the same day as John F. Kennedy and Aldous Huxley:

In 1962 he did a final eight lectures on John Donne and his poetry. It was very cold. Lewis was wearing a hat and very long scarf and a very thick coat. He started to lecture immediately as he came through the door. The room was full of people sitting on the windowsills, sitting on the floor.

As he wound his way to the lectern, he was getting his coat off and his scarf and his hat. By the time he had done all that, you’d already had five minutes of a brilliantly delivered lecture. The fun was at the end of it: He reversed the process precisely. He kept lecturing while he got dressed for the outside chill. His last words were uttered as he fled through the double doors.

I asked Lennox for his most important advice to Christian students. He replied,

To love the Lord with their mind and begin to take Scripture seriously, because in our university system the problem is the two speeds of education. Their professional education goes up very rapidly, but their education and knowledge of God through his Word remains almost at Sunday school level. I would want to encourage them very strongly to build up their confidence in God and his Word.

Final question: “Advice to non-Christians?” Lennox: “I would want to drive a very big hole in their notion that science has somehow made it impossible to believe in God.”