by David Swanson

The imagination calls up new words, new images, new analogies, new metaphors, new illustrations, new connections to say old, glorious truth. Imagination is the faculty of the mind that God has given us to make the communication of his beauty beautiful. –John Piper

I begin with two assumptions. First, John Piper is correct about the magnitude of the imagination to the Christian life. How else can we relate to our spiritual ancestors, distant in time and culture? The teachings of Jesus demand his hearers to imagine a different way of living; his parables draw us into worlds we’ve never experienced. Scripture is filled with the poetic, apocalyptic and prophetic along with nail-biting and head-scratching narrative. Imagination helps me participate in this active Word of God; it’s what moves me from an observer to an accomplice. Through a Christ-centered imagination history becomes my story, poetry becomes my prayer, and the coming Kingdom of God becomes my reality.

Second, Christian imagination is either stimulated or sedated by our surroundings. Having recently made the transition from the suburbs to life and ministry in Chicago, I’m convinced that our environment either hinders or stimulates this overlooked facet of discipleship. Consider a few generalizations from my previous and current zip codes.

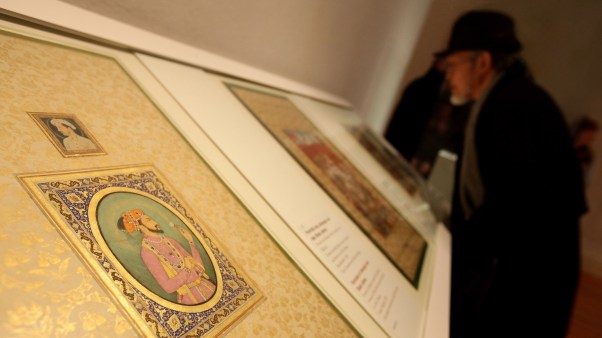

Art

Music, theater, visual arts and film all prod us to consider the world in new ways. Chicago has dozens of small theaters, film festivals and galleries of all kinds. A woman from our church recently staged a series of one-person Bouffon clown shows; something I didn’t even know existed until she invited my wife and I to a performance. With few exceptions, suburbia’s artistic exposure comes from one place: the megaplex. The movies consumed at these theaters generally reflect Hollywood’s interest in the box office bottom line. The aesthetic quality of standard megaplex fare can be argued, but there is no comparison with the myriad of imagination-provoking artistic venues found in the city.

People

The suburb we moved from was 90% white, reflecting well my own skin color. Our new Chicago neighborhood is mostly made up of Polish and Mexican families. The ethnic and cultural diversity of city life exercises my imagination. I can’t help but wonder about my neighbors’ lives, customs and values. How does the priority of extended family held by some of my neighbors differ from my values of independence and autonomy? How does the immigrant experience of other neighbors affect their view of God?

History

Some friends and I once considered opening a coffee shop. While we wanted the shop’s name to connect with our suburb’s culture and history, it became clear that anything we chose would be just as meaningless as the brand names that would surround it. Why? Because suburban life is ahistorical. While an interesting story exists about any town’s beginning, that history has been covered with architecture and branding designed to blend in with every other suburb. In contrast, our American cities are famous for their histories. Chicago is know for the Great Fire in 1871, the world’s first skyscraper in 1885, the World’s Fair in 1893, years of racial division between the city’s north and south sides, the largest Polish population outside of Warsaw, and a cursed baseball team that hasn’t won the World Series in a century. Even a cursory awareness of this history is enough to provoke the imagination. Monuments to the Great Fire, buildings from the World’s Fair, Polish Catholic cathedrals and Wrigley Field all invite questions and stories.

I’ve made some big suppositions thus far, but let’s assume that in general the city provides more imagination stimuli than does the suburbs. (I’ll not comment on rural imagination since I’ve not lived in that setting.) One implication of this has to do with our preaching and worship. When preaching to our city church I assume that people bring with them a robust imagination. Their environment makes it easier to connect with such Biblical themes as grace, justice, sin, liberation and God’s majesty. More so than their suburban kin, these folks regularly interact cross-culturally making the leap into the ancient world of the Bible a bit easier. Songs about God’s coming reign seem slightly less abstract to those who regularly encounter their astonishing world through the arts and cultural diversity.

What then for those called to serve congregations with less vigorous imaginations? Here are two brief observations and I’m curious to hear your ideas. First, the suburbs are never as culturally barren as they appear. There is art, diversity, and history to uncover for those willing to look. Could a local congregation become adept at pointing these out to their suburban neighbors? The possibilities seem great for a church that is committed to understanding and validating these hidden gems. Second, in reference to the quote above, a church that enlivens the imagination will make God’s beauty beautiful in ways rarely experienced by those raised on a bland cultural diet. Instead of imitating the benign aesthetics of suburbia, what if churches preached, worshiped, and celebrated the Lord’s Table such that people’s imaginations were engaged in ways the surrounding cultures couldn’t hope to copy?

Our churches ought to be communities of imaginative people who celebrate God’s past faithfulness and wonder over his future victory. The challenge of enlivening these Christ-centered imaginations is great, and for those in the suburbs the challenge is greater still. But just imagine the possibilities.