Hello, fellow wayfarers … Why the tech-bro oligarchy has no place for Jesus … What pastors and ministry leaders can do to help me help others with some ethical dilemmas … How one scholar went from reading The Screwtape Letters as his first book at 18 to writing a magnus opus on what we can learn from the Black church … Plus, an esteemed historian shows us his Desert Island Bookshelf … This is this week’s Moore to the Point.

Why the Tech-Bro Overlords Want Jesus Out of the Way

It’s been a long, strange trip from George Washington to Elon Musk—and maybe we should ask if that has anything to do with Jesus.

For many years, some of us have warned that this moment’s technological platforms would lead us to the point of constitutional crisis. Most of us, though, meant that this would happen indirectly—through the erosion of social capital and the heightening of polarization by social media. Few of us foresaw the crisis happening as directly as it has: with Elon Musk, the world’s richest man, and a small group of 20-something employees having virtually unilateral veto power over the funds appropriated and the legislation passed by the United States Congress.

There are, of course, massive constitutional, social, economic, and foreign policy implications to this time, implications that will no doubt reverberate through the decades and perhaps even the centuries. But what if there are theological causes and effects too?

Nicholas Carr was one of the early Paul Reveres warning of what digital technology would do to human attention spans. He writes in his new book Superbloom: How Technologies of Connection Tear Us Apart about what the most techno-utopian, “move fast and break things” Silicon Valley barons of industry have told us all along: that behind their project was not just a way to make money (although it’s certainly that) but also a particular view of human nature.

Meta founder Mark Zuckerberg’s statements, for example, would speak of the social network as a “graph”—which is, Carr notes, “a term of art borrowed from the mathematical discipline of network theory.”

“Underpinning Zuckerberg’s manifesto was a conception of society as a technological system with a structure analogous to that of the internet,” Carr writes. “Just as the net is a network of networks, so society, in the technocrat’s mind, is a community of communities.”

Carr argues that Zuckerberg had long held to “a mechanistic view of society,” observing that “one of the curiosities of the early twenty-first century is the way so much power over social relations came into the hands of young men with more interest in numbers than in people.”

The mechanistic view of society is widespread—almost unanimous, though manifesting itself in different forms—among the architects of the social media–artificial intelligence–virtual reality industrial complex. For example, OpenAI CEO Sam Altman created disturbance across the world last week when he suggested that the type of generative artificial intelligence he sees around the bend will result in changes being “required to the social contract, given how powerful we expect this technology to be,” noting, “the whole structure of society itself will be up for some degree of debate and reconfiguration.”

This mechanistic view is not just of society, writ large, but of the human person. For years, comedians have laughed at the “creepy” tech venture capitalists who would, for instance, allegedly seek blood transfusions from younger donors to maintain their own youth and vitality. People would wave away as fringe those like tech leader Ray Kurzweil, who would speak of uploading his consciousness to a computerized cloud in order to live forever. Few paid enough attention to such figures to hear the chilling echoes of Genesis 3 in the answer Kurzweil gave to the question of whether God exists: “Not yet.”

In the past few weeks, my colleague Kara Bettis Carvalho examined tech entrepreneur Bryan Johnson’s claims in the Netflix documentary Don’t Die that he could engineer his body to escape mortality. Once again, few seem to hear the reverberations of Genesis 3: “You shall not surely die” (v. 4, ESV throughout).

All of this is easy enough to chalk up to “creepy” people with fringe positions and an endless supply of money. But this ideology is now not only inhabiting an entire technological ecosystem—to which we are all entwined—but also is the driving factor behind decisions about whether children in Africa get the funds allocated to save them from starvation or AIDS, and whether the constitutional checks and balances of power among equal branches dies in front of our eyes.

And that’s what brings us to the question of God.

Several years ago, Elon Musk told Axios journalists Mike Allen and Jim VandeHei that human beings “must merge with machines to overcome the ‘existential threat’ of artificial intelligence.” When pressed about what this means for our sense of reality, Musk said that we should question whether reality is itself real. “We are most likely in a simulation,” he said, elsewhere noting that the likelihood that we’re not living in a simulated world is only one in billions. The implication is clear—maybe on the other side of the veil of the universe around us is a cosmic Elon Musk.

Seeing humanity and the rest of the “real” world through the metaphor of machine has consequences. Seeing humanity and the rest of the world through the metaphor of data is more dangerous still. Once one interprets the universe through a grid of mechanistic mastery—believing what counts is what’s quantifiable and measurable—the end result is a disrespect of the sanctity of a human nature that cannot be understood that way. And once one sees all limits as arbitrary and “analog,” why would one stop at the limits of norms and traditions and laws and constitutional orders, the things that make up a society?

Ultimately, the “cold” illusion of mastery and the “hot” eruption of chaos prove not to be opposites but two aspects of the same horror. The mindset that sees humanity and society as data to be manipulated naturally gives way to the will-to-power that sees no limits to the appetite and the libido. Elon Musk named one of his children “X Æ A-12” (before having to remove the Arabic numerals for the sake of California law), a “name” reminiscent of a QR code or a serial number, while also fathering children with multiple women. Why would fidelity matter if the world is just data? What are the consequences if the world is a simulation that could be rebooted?

“God” is no problem in this view of reality. After all, the word God can be made abstract and even algebraic. Albert Einstein suggesting that “God does not play dice with the universe” implicated an impersonal structure, a logic, not the living God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Spinoza’s “God” will never summon a person before a judgment seat. The words God or religion can be used as stand-ins for the very sort of self-deification the tech-bro ideology and all its successors demand.

Jesus, on the other hand, is not easily dismissed. Once he is heard—not as a theoretical avatar giving authority to some ideology, but for the actual words he spoke, the actual gospel he delivered—the ambitions of every would-be “master of the universe” stand exposed. Dostoevsky’s Grand Inquisitor in The Brothers Karamazov said he wanted Jesus silenced because the Jesus of the Bible didn’t “understand” human nature: that what people really want is the filling of appetites and the spectacles of distraction. Against the Inquisitor’s diatribe, though, Jesus, as with Pilate, simply stands there, with a look that pierces through all the manipulations of a mechanistic view of the universe.

The digital view of humanity cannot fit with the vision of James Madison and the framers of the American constitutional order. Utopian revolutionaries have always offered some version of “One must break a few eggs to make some omelets,” regardless of the price of actual eggs at the moment. But behind that utopianism is always a theology—and the theology can co-opt almost everything. Christianity can be co-opted by a digital utopianism, but only by silencing Jesus.

Yet Jesus is not easily silenced. The universe is no simulation. It is created and held together not by an algorithm but by a Word. And this Word is no abstraction to be decoded but a person, one who “became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14). A million different Babels lie in the ruins of history, and behind them a million different Nimrods, all of whom would storm the limits of mortality and of accountability to create simulations of themselves and of their rule. They are all gone, and they cannot be rebooted.

The tech-bros have inherited the earth, for now. That’s not their fault. It’s ours. We have believed what they told us about ourselves: that we are ultimately just data and algorithms to be decoded, appetites to be appeased. And because of that, we’ve looked for programmers and coders to keep our simulation going—what previous generations would have called “gods.”

In his inaugural sermon at Nazareth, Jesus read from the scroll of Isaiah the prophet, recounting the “good news to the poor” that comes with “the year of the Lord’s favor” (Isa. 61:1–2; Luke 4:18–19). That same prophetic book taught us to pray, “O Lord our God, other lords besides you have ruled over us, but your name alone we bring to remembrance” (Isa. 26:13).

After all the promises of the tech-bros are gone, Jesus abides.

Pastors and Ministry Leaders: Send Me Your Ethical Dilemmas

I’m working on a special project launching later this year—which I can’t tell you about now, but I will later. For the moment, though, I need the help of those of you who are pastors, church staff members, ministry or lay leaders, or ministry spouses.

Send me the difficult situations you are facing—the conundrums for which you need counsel or advice as you try to discern what is the right thing to do—and upload them for me at this site:

If your submission is selected, it will be read aloud in a recording and/or included in a regular column. All entrants have our commitment to confidentiality; we will not post, publish, or air your name or contact information.

From The Screwtape Letters to the Black Church

On the podcast this week, I talked to Walter Strickland, a scholar who told me about how he never read a book until he was 18 years old. That book was C. S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters. Strickland made up for lost time and is now the author of a massive two-volume work on the Black church’s theological, historical, ethical, and spiritual contributions to the rest of the body of Christ.

Strickland discusses how and why slaveholders used biblical texts to justify the terrorism against enslaved people, and what that should tell us about how to sense when a person, an institution, or a culture is similarly misusing the Word of God for Wormwood ends. We also talk about what we all can learn about how to proceed in this difficult time from the ways the Black church withstood evil, formed community, and appealed to the consciences of others.

You can listen to it here.

Desert Island Bookshelf

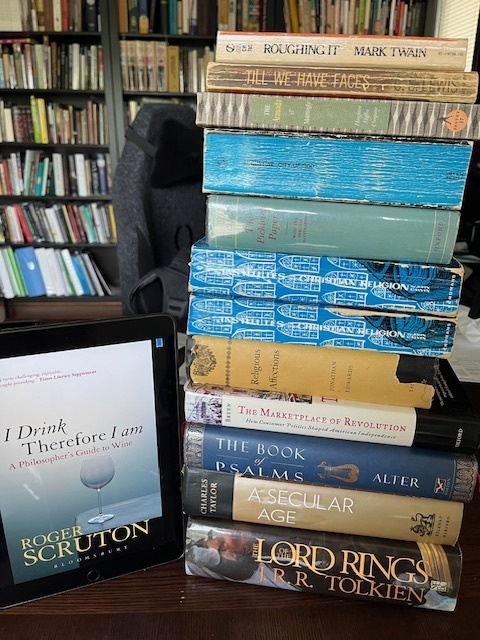

Every other week, I share a list of books that one of you says you’d want to have on hand if you were stranded on a deserted island. This week’s submission comes from esteemed professor of history Timothy D. Hall at Samford University in Birmingham, Alabama:

- J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings series needs no explanation.

- Charles Taylor’s Secular Age repays every fresh read.

- Robert Alter’s translation of Psalms: Alter’s translations of the Hebrew Bible are powerful and deliver jolts of fresh insight on every page. This volume is no exception. The notes are priceless.

- T. H. Breen’s The Marketplace of Revolution: I first heard Breen present a paper at an early stage of his research on this book when I was just starting as a grad student at the University of Chicago. I had never heard anyone do history like that before. I followed him up to Northwestern to earn my PhD under him.

- Jonathan Edwards’s A Treatise on Religious Affections is filled with profound beauty and soaring insight.

- John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion are too. Many passages in both have moved me to tears and will again on the next read. Their God—my God—is surpassing in beauty, glory, majesty, love, and grace.

- Charles Dickens’s The Pickwick Papers is just pure fun. G. K. Chesterton said of it, “To every man alive, one must hope, it has in some manner happened that he has talked with his more fascinating friends round a table on some night when all the numerous personalities unfolded themselves like great tropical flowers. All fell into their parts as in some delightful impromptu play. Every man was more himself than he had ever been in this vale of tears. Every man was a beautiful caricature of himself. The man who has known such nights will understand the exaggerations of ‘Pickwick.’ The man who has not known such nights will not enjoy ‘Pickwick’ nor (I imagine) heaven.”

- Saint Augustine’s City of God: Love him or not, you cannot understand the long history of Western culture (and Christianity in the West) without him. Peter Brown describes him as pushing along “cumulus clouds of erudition” in this book.

- Garrett Mattingly’s The Armada remains one of the best works of history written. So much fun! Leaves you cheering for Hawkins and Drake.

- Till We Have Faces is C. S. Lewis’s most beautiful novel all about “amour propre v agape.” It is also about longing for home—that indescribable pang that strikes unexpectedly in a song, or instrumental music, or story, or a piece of art that calls you toward a place you have never yet been, the Source of all joy.

- Mark Twain’s Roughing It is a blast—it is a memoir of his years in the Nevada Territory, where his brother welcomed him and got him started in journalism after he deserted the Confederate army in Missouri toward the beginning of the Civil War.

- Roger Scruton’s I Drink Therefore I Am is alternately funny, snobby, profound, and in the end, beautiful. I don’t suppose I’d be able to grow grapes on that desert island?

Thank you, Professor Hall!

Readers, what do y’all think? If you were stranded on a desert island for the rest of your life and could have only one playlist or one bookshelf with you, what songs or books would you choose?

- For a Desert Island Playlist, send me a list between 5 and 12 songs, excluding hymns and worship songs. (We’ll cover those later.)

- For a Desert Island Bookshelf, send me a list of up to 12 books, along with a photo of all the books together.

Send your list (or both lists) to questions@russellmoore.com, and include as much or as little explanation of your choices as you would like, along with the city and state from which you’re writing.

Quote of the Moment

“I believe in dignity; not in dignity’s old shadow of puffery and self-importance, but in its power to keep us true to our own spirit. With dignity comes honesty and an unwillingness to sell yourself short, to temporize or collude in cowardly ways that may preserve our jobs but not our honor.”

—David Whyte

Currently Reading (or Re-Reading)

- Volker Leppin, Francis of Assisi: The Life of a Restless Saint (Yale University Press)

- Kurt Vonnegut, Slaughterhouse Five (Dial Press)

- George Eliot, Silas Marner (Penguin Classics)

Currently Watching

We have seen two episodes of the new Hulu series Paradise. I can think of only a handful of times in the past decade (Broadchurch was one) in which a television included a genuinely surprising plot twist. We plan to keep watching.

Join Us at Christianity Today

Founded by Billy Graham, Christianity Today is on a mission to lift up the sages and storytellers of the global church for the sake of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Subscribe now to get exclusive print and digital content, along with seasonal devotionals, special issues, and access to the full archives. Plus, you’ll be supporting this weekly conversation we have together. Or, you could give a membership to a friend, a pastor, a church member, someone you mentor, or a curious non-Christian neighbor. You can also make a tax-deductible gift that expands CT’s important voice and influence in the world.

Ask a Question or Say Hello

The Russell Moore Show podcast includes a section where we grapple with the questions you might have about life, the gospel, relationships, work, the church, spirituality, the future, a moral dilemma you’re facing, or whatever. You can send your questions to questions@russellmoore.com. I’ll never use your name—unless you tell me to—and will come up with a groan-inducing pun of a pseudonym for you.

And, of course, I would love to hear from you about anything. Send me an email at questions@russellmoore.com if you have any questions or comments about this newsletter, if there are other things you would like to see discussed here, or if you would just like to say hello.

If you have a friend who might like this, please forward it, and if you’ve gotten this from a friend, please subscribe!

Russell Moore

Editor in Chief, Christianity Today

P.S. You can support the continued work of Christianity Today and the Public Theology Project by subscribing to CT magazine.

Moore to the Point

Join Russell Moore in thinking through the important questions of the day, along with book and music recommendations he has found formative.

Delivered free via email to subscribers weekly. Sign up for this newsletter.

You are currently subscribed as no email found. Sign up to more newsletters like this. Manage your email preferences or unsubscribe.

Christianity Today is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International.

Copyright ©2025 Christianity Today, PO Box 788, Wheaton, IL 60187-0788

All rights reserved.