In late spring across the Eastern United States, the shrub Lonicera maackii enters into its glory. It enrobes itself in cream-and-white blossoms that smell of citrusy syrup and drift to the ground as the days warm. By early autumn, its branches pop with shiny, pulpy berries that can linger into winter, a Christmas backdrop as lovely as mistletoe or holly.

October is the best month to kill this plant. But if you’re busy then, really anytime will do.

East Coasters and Midwesterners once loved Lonicera maackii, better known as Amur honeysuckle. It was introduced into the US in 1898 by Niels E. Hansen, a Lutheran horticulture professor dispatched by the Department of Agriculture to scour the world for exotic plants that Americans might want to take for a spin. He told his students that he felt, as a botanist, he was “doing the Lord’s work.”

Hansen journeyed from Europe to China—by wagon, by train, and, for 700 miles, in a sleigh. He bagged carloads of specimens, shipping them back across the Atlantic. Among the first few hundred seeds was Amur honeysuckle.

The Department of Agriculture liked what it saw in this fast-growing, fruity shrub. It imported more from Britain and from Manchuria, the honeysuckle’s homeland. From the 1930s to the ’80s, the government’s Soil Conservation Service distributed the plant to farmers and landowners across the United States to curb erosion and restore wildlife habitats.

We all make mistakes.

By the 1960s, folks from Chicago to Cincinnati were cursing the bush as a weed. Amur honeysuckle, also called bush honeysuckle, spreads like gossip and is nettlesome to eradicate. It leafs earlier than other trees and clings to its leaves longer, robbing native wildflowers and saplings of sunlight. It excretes chemicals into the soil that stunt nearby plants. It boosts tick populations.

In short, Lonicera maackii is the worst. It’s banned from being sold in several states, and at least ten others blacklist it as an invasive species or as a “noxious weed.” Where I live in Kentucky, a region that supplies much of the nation’s valuable hardwood timber, forest managers watch helplessly as Amur honeysuckle floods the understory and smothers future generations of trees.

Bush honeysuckle simply wears people out. Billy Thomas, a forester at the University of Kentucky, calls it “a booger” and “our old nemesis.” He says for anyone with ears to hear, “If you’ve got one or two plants on your property, now’s the time to get them out of there.”

I’ve obliged. Over the years, I’ve sawn, hacked, and poisoned the plant away from the edges of my property. I’ve trucked away more than 30 cubic yards of brush. I nearly lost a finger to a chainsaw while chewing into a 20-foot-tall thicket. More than once, I’ve slipped and fallen on the berry mash that accumulates underfoot when wrangling the felled limbs.

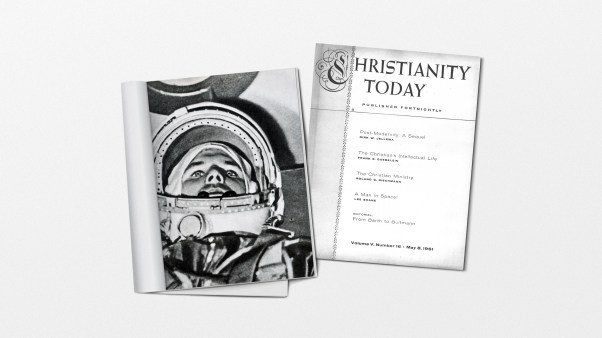

Maybe it’s a kind of spiritual discipline. Gardeners tout weeding as the surest way to grasp all the Bible’s talk of thorns and thistles; we don’t fully contend with the curse of the ground until we sink actual shovel into hard dirt. “We could stand side by side, Adam and I, he in his skin shirt and I in my grubby jeans, hoeing, stopping to tear out an upstart cocklebur,” the writer Virginia Stem Owens mused in Christianity Today in 1976. “We inhabit the same spiritual space.”

I can’t disagree. Spend a day rescuing a strawberry patch from a tide of Bermuda grass—disentangling the tentacular runners of one plant from another—and you’ll relate to Christ’s parable of the wheat and the tares in ways you wished you didn’t.

Likely thousands of sermons have contemplated weeds. Some are weirdly laudatory.

Augustine, in his fight to prove the material world was not evil, argued that thorns and thistles, as part of God’s creation, were, in fact, good. He envisioned weeds as a sort of biological Babel, a divine gift to restrain our worst impulses. “Even such herbs have their measure and form and order, which whoever considers soberly will find praiseworthy,” he wrote.

In a similar vein, Charles Spurgeon preached a real downer of a message in the late 1800s. While Londoners likely were readying their spring gardens, the Baptist pastor delivered 5,200 words about thorns and thistles, as if to brace his congregants for the toil that lay ahead. He said—Chin up!—that weeds are a sign of God’s mercy: The Fall could have been worse. Instead, the resulting curse does not strike Adam directly but “glances obliquely and falls upon the ground whereon he stands.” (Did Spurgeon ever wake up blistered from poison ivy the day after clearing a fence line?)

Figurative weeds have infested every sphere of existence, Spurgeon assured his congregants at Metropolitan Tabernacle—from the natural world, where ships are tossed at sea, to the social order, where hucksters swindle and families disintegrate, to the “little world of your own self.” Weeds will grow unbidden for everyone, for the righteous and the unrighteous. “All the prudence and care, ay, and all the prayer and faith that you can summon to your help, will not keep you clear of these thorns and thistles,” Spurgeon said.

As sermon fodder, Scripture’s weed metaphors are a capacious bunch, coming in a surprising variety much like weeds themselves. The Old Testament writers described evildoers as briers (Mic. 7:4) and rebellious people as thorns (Ezek. 2:6). Jesus, for his part, likened false prophets to thistles (Matt. 7:15–16). He told his disciples, in his story about the sower, that thorns represent “the worries of this life and the deceitfulness of wealth” (13:22). He bore a crown of thorns at his crucifixion.

Illustrations by Tim McDonagh

Illustrations by Tim McDonaghAll those weeds descend from their root metaphor in Genesis, where thorns and thistles first poke through the dirt as consequences of sin, standing in for dysfunction and toil (3:18). A common characteristic unites the nuisance plants of the Bible: We brought them upon ourselves through the door of our disordered desires.

But Moses, bless him, didn’t know about Amur honeysuckle when he penned Genesis. He probably didn’t foresee a globalized world where weeds would jump continents, or a world where our speech and politics betray a subtly revised understanding of evil—not as a product of our own hearts but as a foreign incursion.

The first recorded instance of the term invasive species may have been in a British colonial journal in 1891, around the time Spurgeon preached his weed sermon. But plants and animals have been hitchhiking the world in earnest from the dawn of colonization.

We Americans have imported exotics since Christopher Columbus first dropped anchor. He’s thought to have brought lettuce, actually an Egyptian innovation, to North America. Also he brought the cow. Seafarers carted tomatoes and potatoes from the New World, where they originated, to the Old World and back again. Other favorite non-natives include honeybees and, though their belovedness is debatable, cats.

Some species, however, multiplied without our blessing. In Argentina in the 1830s, Charles Darwin stumbled upon impenetrable fields of European artichokes and thistles stretching for miles where “nothing else can now live.” (He also called it “an invasion.”) In 1898, the same year Hansen pocketed his first honeysuckle seeds, H. G. Wells published his novel The War of the Worlds, styling his Martian “red weed” after Elodea canadensis, an aggressive North American stowaway sea plant that now excels at clogging European waterways.

Today, there are more than 11,000 non-native species in the United States (the official count includes viruses, bacteria, and fungi). The result is that, according to US Geological Survey data, if you live in Hawaii or Napa Valley or Miami or Monroe, Louisiana, immigrant flora and fauna now define your landscape.

Not all exotics are weeds, and not all weeds are invasives. A weed, generally speaking, is any plant in our personal environments that gets on our nerves. When Spurgeon spoke of weeds as a metaphor for sin and evil, invasives weren’t yet a thing. He almost certainly had native plants in mind.

When exotic species turn on us, however, biologists slide them to the naughty list. Non-natives get labeled as “invasive” when they leap ecological fences and begin destroying wildlife or harming people. Some invasives—particularly in the animal kingdom—inspire our terrified fascination: mussels clogging municipal water systems, pythons strangling the Everglades, giant spiders parachuting into New York. But some plants among the invasive ranks may surprise you. Burning bush? Its foliage is striking, but it spreads like, well, wildfire. Bamboo? You’ll never be rid of it. English ivy? Something called tree of heaven? And wait, daylilies?

It turns out there are people who study runaway plants and animals. The field of invasion biology sprouted in the early 1980s, a few decades after English zoologist Charles Elton published The Ecology of Invasions by Animals and Plants, which popularized the idea that invader species could overwhelm and harm indigenous wildlife. Today, hundreds of invasion scientists publish in their own scholarly journals. They produce tomes of research, striving to understand when a non-native turns bad and when it is just fine.

A field with such loaded vocabulary—colonization, alien species, biological pollution—has sometimes, unsurprisingly, run afoul of cultural censors. Food and plant writer Michael Pollan, for example, is no fan of “nativist” gardening. Plants will inevitably spread on boats, by planes, and in bird droppings, so even many biologists don’t draw a line in the sand between all natives as “good” and non-natives as “wicked.”

Yet as it happens, the reexamination of weeds has coincided with a shift in the ways Americans talk about moral evil.

Just as invasion science was taking off, presidential candidate Pat Buchanan turned the language of “culture wars”—a term popularized in 1991 by sociologist James Davison Hunter—into a battle cry. At the 1992 Republican National Convention, Buchanan railed against the sinister agenda liberals wanted to “impose” on America.

Dubbing the struggle a religious and cultural “war,” Buchanan struck a tone in many ways similar to that of a conservationist warning about environmental threats. He painted the nation as an unspoiled tract of land, calling Democratic ideas “not the kind of change we can tolerate in a nation that we still call God’s country.” He spoke of the need to shield “small towns and communities” from the “raw sewage of pornography that pollutes our popular culture”—as if provincial places were unacquainted with sexual temptation before it encroached like some kind of escaped bacteria.

The invading-horde rhetoric has only grown more intense since. Consistent references to immigrants and refugees as a disease-carrying “invasion” are a relatively recent political phenomenon. President Donald Trump has branded his opponents as hazardous pests by labeling them “vermin.” In a video debuted at the National Religious Broadcasters convention in 2024, then-candidate Trump was draped in messianic garden metaphors in an AI-modified play on Paul Harvey’s iconic “So God Made a Farmer” speech: God wanted someone to “fight the Marxists” and other looming threats. “God looked down on his planned paradise and said, ‘I need a caretaker.’ So God gave us Trump.”

Even the administration’s repeated invoking of “the enemy within” is invader talk masked in introspection. Neither Trump nor Vice President JD Vance has deployed the phrase in service of self-reflection. In a February speech in Germany, Vance used it explicitly to reference those he sees as opposing nativist agendas; after the speech, he met with the leader of a growing political party that embraces racial ideals from Germany’s Nazi past.

Of course, no one is shocked anymore by othering language in politics. And Republicans don’t practice it alone: Remember when Democrats, led by Minnesota governor Tim Walz, tried branding conservatives as “weird”? The impulse is understandable. Christians know they have an enemy out in the world seeking harm. I, too, am wary of the Devil’s schemes.

But then, there’s the Bible. From the opening pages, it invests a lot of ink imploring us to examine ourselves, often with tricky turns of phrase. God alerted Cain, Scripture’s second soil-worker, that “sin is crouching at your door” (Gen. 4:7). Like an invader! Except God was not cautioning about some outgroup; he was calling out the sin already at work inside Cain’s angry heart.

Exoticizing shrubs has its uses. But exoticizing evil—or other people—endangers the soul. Jesus chided the Pharisees that their fixation on foreign evils had blinded them to the weediness of their own sin: “For it is from within, out of a person’s heart, that evil thoughts come” (Mark 7:21–22).

Spurgeon put it more practically for his audience in London. Anyone who looks will “find great crops of thistles springing up in their hearts,” he said, “and they have to keep the sickle of sacred mortification going to cut them down.”

Our most loathsome invasive plants weren’t foisted upon us. Almost without exception, we loosed them upon ourselves.

Kudzu is the quintessential American case study. Gardeners fell in love with this fuzzy vine, a cousin to peas, when it was introduced in the Japanese pavilion at the 1876 Philadelphia world fair. Its three- to four-inch leaves resemble mittens. It grows wicked fast, capable of covering the length of a subway car in a single season. Plant it as an ornamental, and in no time its shady foliage could cover a front porch or an unsightly bare patch like some tropical gift wrap.

A Quaker couple, Charles and Lillie Pleas, were the first farmers to grow kudzu commercially. In the early 1900s, they sold mail-order root crowns and seedlings from their North Florida nursery. (The post office briefly investigated them for mail fraud, skeptical that any plant could be as prolific as they advertised.)

Then in the late ’30s, kudzu took off. Relentless cotton cultivation had ravaged Southern soil. Researchers found that kudzu swaddled the dirt so tightly it all but eliminated erosion. Also, cows had a taste for the plant. So states stuck it on road banks. Farmers blanketed fields with it. The feds grew a hundred million seedlings and paid farmers to plant them.

No one cheered kudzu more loudly than a Baptist pastor’s kid named Channing Cope. A newspaper editor and self-taught conservationist, Cope tried kudzu for himself on his Yellow River Farm near Atlanta. By the 1930s, he was convinced the exotic plant could deliver Southern farmers from struggle.

Illustrations by Tim McDonagh

Illustrations by Tim McDonaghCope boosted kudzu on his daily radio show for Atlanta’s WCON, recorded from a rocking chair on his front porch, and in his newspaper column with the Atlanta Constitution. He showed government agents and foreign officials around his kudzu fields. He founded the Kudzu Club of America, which at one point encompassed more than 20,000 members; held an annual convention with “kudzu queen” pageants; and aimed to plant 8 million acres of kudzu across the South.

Cope spoke about the vine in revivalistic tones. “A strange ecstasy lifts Southern growers’ hearts and exalts their language when they get together to praise kudzu,” Cope said during an interview in Reader’s Digest in 1945. In his Constitution column, he called the plant “the Lord’s indulgent gift to Georgians” and said hundreds of thousands of acres awaited “the healing touch of the Miracle vine.” In The Farm Quarterly in 1949, Cope wrote, “The South believes the Almighty had its cottoned-out gullies and hillsides in mind when he designed the wonder crops, kudzu.”

Cope died in 1961, a modest celebrity in the South. You’ve probably heard the rest. Things got out of hand, and we fell out of love with kudzu. Old cars disappeared in ropy clouds of green. Barns were crumpled and trees uprooted beneath kudzu mats weighing hundreds or thousands of pounds. Monikers piled up: “the vine that ate the South,” “cuss-you,” “strangling vine,” “foot-a-night vine,” “mile-a-minute vine.”

Today, kudzu is an adversary of the Department of Agriculture and the governments of more than 30 states. It has trekked as far as Oregon. Researchers calculate it has cost the forestry industry alone hundreds of millions of dollars. If the vine has sunk its meaty tubers into your land, thoughts and prayers to you.

Kudzu’s tale is one of unintended consequences. Cope, like Hansen with his honeysuckle, clearly meant well. He knew of the vine’s penchant to transgress; in his 1949 book Front Porch Farmer, Cope said cultivating the vine was fighting “fire with fire.” He just believed we could contain the fire.

We couldn’t. The flames were fanned by what theologian Reinhold Niebuhr called “collective egoism”—the concept that sin not only infects us as individuals but also knocks the whole of society out of alignment. So even our best contributions to the world carry the potential, for reasons we don’t understand, to miss their mark and muck things up.

No obvious sin lurks behind the tragic story arc of many invasive species. Cogongrass, a razor-sharp grass in the Deep South that destroys every plant in its path and intensifies wildfires, debuted in Alabama in 1911 as packing material from Japan. What exactly is the lesson there?

Matthew Henry, the great English Presbyterian minister, saw a kind of Pandora’s box in non-native plants. Preaching at the outset of the 18th century, when gardening with alien plants was largely an aristocratic hobby, Henry seemed suspicious of the growing affection for exotics. He heard a warning in the prophet Isaiah’s singling out of Israel’s “imported vines” (17:10). “This was an instance of their pride and vanity,” Henry wrote in his influential Bible commentary. Their “ruining error” was “their affection to be like the nations,” he said. Not content with what they have, “they must have flowers and greens with strange names imported from other nations.”

As far as I know, the Bible doesn’t pooh-pooh botanical variety. Martin Luther famously wrote to a friend, in a letter now housed at a museum in Wittenberg, “Just get me even more seeds for my garden, if ever possible many different varieties.” But Henry’s concern was that coveting fruits beyond those God has already given us can reveal weediness in our own hearts. What might he have said to Cope?

The Kudzu King, as Cope was known, battled his own inner invasives. Records show his mother divorced his minister father when Cope was 13, alleging “cruel treatment.” At age 14, Cope was arrested for breaking into a safe at a Louisville library and stealing $125. (Yet only a year later, Cope, as a young Navy seaman, dove from a boat in Rhode Island to save a drowning man.)

Cope held onto scraps of his Baptist upbringing throughout his life; he wrote a Christmas column in 1947 declaring to Constitution readers that Jesus was the only leader in history who offered durable hope. Even so, in a 1949 Time magazine profile, Cope comes across as a glutton with a bourbon problem.

Some biographers have portrayed Cope as a vainglorious fool. Maybe he was. Or maybe we see what we want to see when we flatten people as if they were plants. Perhaps, more charitably, Cope simply over-relied on kudzu to cover the scars of his own struggles.

Cope’s tangled legacy highlights an insidious tendency of framing evils as invasive: We mythologize them. The internet buzzes with apocryphal claims about kudzu—that it covers millions of acres throughout the United States, that it’s devouring an additional 150,000 a year, that at night it carries away children sleeping beneath open windows. But the US Forest Service’s own data vary wildly. The vine covers 2 million acres, it says. Or maybe 7 million. It only spreads by 2,500 a year. Actually, it might be in retreat.

Bill Finch, an Alabama horticulturalist with newspaper columns and radio programs of his own, contends that “the vine that ate the South” in fact didn’t. He calls kudzu “the most silly plant hoax of the past century.” He took his case against the lore all the way to the pages of Smithsonian magazine. Finch even says kudzu is not that hard to kill. Just mow it regularly. Or buy a few goats.

Christians know better than to overlook evil, of course. Where there are weeds, they must be pulled. But dealing with sin does not require mythologizing it—the way Pat Buchanan characterized small towns as spotless and vice as a toxin sent by city folk. In fact, in the weed wars, sensationalizing often obscures the real problems.

Consider salt cedar, a feathery invasive bush from Eurasia that plagues the American West. It has been accused of guzzling water and draining desert water tables. Now, some invasion biologists challenge that claim as urban legend, saying it distracts from the true culprit: human overconsumption of water.

In the South in particular, kudzu is a favorite sermon illustration for sin. (You can Google it.) And in many ways, it’s apt: Sin is only countered with vigilance. Libertine ideas come to the church from “the world,” not from biblical exegesis. But the image has limits. Sin, like most invasives, is tracked in on the boots of churchgoers.

Invade is a personifying word. In its earliest Latin use, it implied hostility with agency. Invasion rankles when we apply it to, say, desperate immigrants—a mother cradling an ailing child certainly does not feel hostile. And invasion should grate when we apply it to sin, because sin has no agency of its own. For nearly two millennia, the church has taught that everything God made is good and that evil is not a force in itself but a corruption of the good.

We challenge the goodness of God’s creation—and perhaps deceive ourselves—when we begin to think of evil as if it were a foreign creature we can vanquish. We step into something like a zero-sum game: It’s us or the invaders.

That’s a game we cannot win. Armed with all the herbicides in the world—or all the prayer and resources and state power we can amass—we still won’t beat the briers. Spurgeon taught that the weeds will always be with us: “The world will always go on bringing forth thorns and thistles” until Christ comes. The tares growing up among the wheat, Jesus said in his parable, are ultimately for him to sort through and uproot at the end of the age (Matt. 13:40–41). It’s a remarkably liberating little story, when you ponder it: The only task given to the wheat, or “the people of the kingdom,” is to be wheat (v. 38).

Why bother fighting weeds then? Does Adam’s mandate to tend the earth still apply if humans aren’t really capable of putting it all to rights?

I put the question to Jim Varick, a retired botanist who lives on 60 wooded acres outside Cincinnati.

“I don’t pretend to know the answer to all of those things,” he told me. Jim and his wife, Julie, have been schlepping bags of invasive garlic mustard (courtesy Europe, 1868) and Japanese stilt grass (courtesy China, 1919) out of the forest for 20 years. “I need to do what he’s called me to do today. And I feel like he’s called me to restore his creation.”

They finished off their bush honeysuckle long ago. As if by magic, a carpet of wildflowers unfurled on the forest floor. “It’s a great feeling, conquering the woods,” Julie Varick said.

The Varicks harbor no illusions about saving the Midwest from invasives. They’re content to steward the small places God has given them, to create glimpses of what life may someday be without weeds. What if a child could sit on the ground and read Jesus’ words about the flowers of the field, then look up and see not woods choked by honeysuckle monoculture but actual flowers—and know that her Father cares for her?

The couple also helps lead a restoration effort on the 70-acre former golf course where their church put up a new building a while back. The congregation, Horizon Community Church, is eradicating invasive plants and rewilding what was once a sea of lifeless turf. They are partnering with Cincinnati Nature Center and organizing workdays and planting truckloads of native trees, shrubs, and grasses.

Jim said he imagines creation as a work of art brushed by the hand of God—balanced, with just the right colors and proportions of negative and positive space. But over the centuries, we spliced in exotic invasives that bled across that canvas like a wound.

“We’re going in there with this beautiful, moody Dutch master painting, and we’re saying, ‘Oh, wouldn’t it be better if it had some bright cheery flowers over here and some happy trees over here?’ And now when we look at it, we’re not getting the message that God intended for that painting.” No one is trying to vandalize anything, Jim said, but “I feel like that has to grieve his heart, when he’s given us this beautiful thing and we, in our infinite wisdom, have decided, ‘That’s really a great start there. But we can do it much better.’ ”

There’s room for disagreement. Go ahead and plant that saw palmetto in your front yard in Massachusetts, if you’d like, even though it most definitely doesn’t belong there. It won’t spread.

Just exercise caution. After all, thinking we could do better than God is what got us booted from the Garden in the first place.

It’s also what led my neighbor to plant invasive English ivy beside her driveway. This summer, I’ll spend a few sweaty hours yanking strands that have crept into my yard—a liturgy, if you will, that calls me ever inward to manage the native sin of my own heart. Pro tip: Pull ivy when the soil is damp for a satisfying snap of the roots. Next year, they’ll be back.

Correction: An earlier version of this story gave the incorrect year that Charles Spurgeon preached a sermon on thorns and thistles. The sermon was published in 1893; the year he preached it is unknown.

Andy Olsen is senior features writer at Christianity Today.