Hello, fellow wayfarers … What I counsel a Christian who is discouraged almost to the point of giving up … How an old book re-amazed me with grace … Why the “crucibles” of your life can point you to new life … A Desert Island Booklist from New Mexico (not going to call it “New America”) … This is this week’s Moore to the Point.

A Word to a Discouraged Christian

“Can you give me a reason why I shouldn’t just give up on religion altogether?”

Before the young man finished his question, I already knew the basics of what he was going to say because I hear it all the time.

This man wasn’t doubting the truth of the creeds or the inspiration of the Bible. He wasn’t wanting to go to a strip club or snort some cocaine. He desperately wanted a reason to stand firm because he loves Jesus and wants to follow him.

He’s shaken, though, by some of the things he’s seen—some cruelty, some nihilism, some hypocrisy—in the name of Christ, by the very people who taught him the gospel.

I don’t handle all of these questions the same way. An Ivan Karamazov who concludes that the presence of suffering and evil disproves a good God needs a different conversation from someone who believes physics explains all the mysteries of the universe. But neither of these were the situation here.

Instead, I was talking to someone who is a convinced Christian but is discouraged and demoralized by some awful and stupid stuff that he’s seen. If that’s you—or someone you love—here are some things I think you should consider.

First, the sense of being rattled is completely normal and understandable. The church is meant to be a signpost to the truth, goodness, and beauty of the kingdom. It is supposed to be an indivisible body to the head that is Jesus Christ. Jesus said, “By this all people will know that you are my disciples, if you have love for one another” (John 13:35, ESV throughout). He prayed, speaking of the church, “They are not of the world, just as I am not of the world. Sanctify them in the truth; your word is truth” (17:16–17).

Someone who has had neglectful or abusive parents has every reason to grieve not having what every child should receive as a matter of course: parents who love, protect, and guide them. When that grieving person talks about this, who but the most twisted would say, “Lots of people have bad parents, and a lot of people had worse—move on”? The first step to “moving on” is, in fact, realizing that this is not the way things were supposed to be.

There’s a way of saying, “The church has always had hypocrites” (which is true, of course) in a way that waves away the genuine expectation of the pursuit of holiness by the church. It can be kind of like hearing a serial killer shrug as he says, “We’re all sinners: Who among us doesn’t have a skeleton or two under the floorboards?” God forbid.

That said, in a conversation like this, I’m not speaking to “the church.” I’m only speaking to this Christian, who is wondering if he’s crazy or stupid to still follow Jesus after all that he’s seen. And—with everything in me—I do not believe that he is.

C. S. Lewis famously warned about “chronological snobbery,” the sense that previous eras were unenlightened and backward and that we have progressed beyond it. I think there might be something analogous to that with what we might call “chronological despondency.”

Imagine how hard it must have been to believe in the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob in the time when Jeroboam was setting up altars to golden calves at Bethel and Dan (1 Kings 12:25–33). How difficult must it have been to believe the apostle’s letter telling you that the word of the cross is the power of God to salvation, when all you have seen is a Corinthian church where people are sleeping with their stepmothers (1 Cor. 5), fighting for a place in line at the Lord’s Supper (ch. 11), and arguing over whether someone ought to speak in tongues (chs. 12–14).

If you were a Christian in first-century Laodicea, you would not have livestreamed services from Philadelphia, and probably would not have even traveled more than a mile or two from where you lived. All you would have seen of the church is what the ascended Christ himself said made him want to vomit (Rev. 3:16). Consider how hard it must have been to be a genuine, convinced Christian when that name was used by the corrupt Borgia crime family or by the murderous Inquisitors.

Now, imagine you are speaking a word of counsel—not to those villainous structures and rulers and clergy—but to one Christian, in one of these time periods, whose heart is “strangely warmed” by the Scriptures, despite all he or she has seen. Would you advise that person to surrender Christianity to those who are using it just because that person happens to be born in a time of awful corruption and deadness?

Now suppose you are living in just such a time of disobedience and lifelessness. What then? If you are convinced, as I am, that Jesus of Nazareth is who he said he was, the son of the living God, why would you allow anyone to take that away from you just because you live in AD 2025 North America rather than AD 125 Antioch or, say, 2065 Malaysia?

The periodic crisis of church structures does not throw into question what Jesus told us but actually confirms it. Jesus told his disciples that the most stable religious fact they could imagine—the temple—would be torn down (Matt. 24:1–2). He said that “the abomination of desolation spoken of by the prophet Daniel” would stand in the holy place (v. 15), that is, the very place of God’s own authority and mercy. Jesus said to his disciples, and then through them to us, “See that you are not alarmed, for this must take place” (v. 6), and “See, I have told you beforehand” (v. 25).

Jesus explicitly said that he was telling this to the disciples beforehand because they would have two seemingly opposite temptations: Some would be tempted to fall for the counterfeits (v. 26) and others would be tempted to lose heart (vv. 6–8). His words are meant for us too. You and I are probably, at least in this case, more in the second area of danger than the first.

The fundamental question is not whether the church as a whole, especially in America, is in dire condition. It is. The question is whether the tomb is empty. If it is, then we can trust that Jesus can overcome even the horrific misuse of his name by those who are confused or plunderous.

A lot has been revealed over the past several years, and it has shown the awful fruit of some of the theology and “worldview” notions that many of us held. Seeing where those things lead should call us to re-examination, tossing aside that which does not conform to the Scriptures and to the Way of Christ Jesus.

In the early 20th century, young Karl Barth was a typical European liberal Protestant who revered those who had taught him his theology. At the outbreak of World War I, however, Barth was horrified to see the names of his own professors on a petition supporting the German nationalism of the Kaiser, deeming it a culture war for Christian civilization against barbarism.

Barth wrote, “An entire world of theological exegesis, ethics, dogmatics, and preaching, which up to that point I had accepted as basically credible, was thereby shaken to the foundations.” This started a process of his asking how the theology of Friedrich Schleiermacher and others could lead to embracing such horror. That question would become even more pronounced when Barth saw almost the entirety of the German church Nazify.

This is not to say that where Barth ended up was necessarily the right place, but it is to say that the shaking of Barth at this point was clearly right. Whatever one thinks of where he ended up, where he went—back to the sources of the Book of Romans and the rest of the Bible—was the right response to a “Christianity” that had proven itself incredible.

What a shame it would be if he and Bonhoeffer and the rest of the tiny minority of dissenters from the German Christian atrocity had simply let the German Christians have the copyright to a gospel they had hollowed out and replaced with what Barth rightly named the “blood mysticism” of the Nazis.

If we wave away the misuse of the name of Christ as “just the way it is,” we are sinning against God and the generations before and after us. If we refuse to ask what ideologies and theologies give birth to cruelty and authoritarianism and antinomianism and legalism, we likewise shirk what we’re called to do.

But for those of us who are convinced that the women at the tomb weren’t lying—that the disciples went to their deaths refusing to recant what they had testified about the one who “presented himself alive to them” (Acts 1:3)—why would we walk away from that? Why would we walk away from Jesus?

Yes, you are situated in a difficult time, a time of testing and tumult for the church. Maybe you would have preferred to live in some other time. But you’re here now, with the same ascended Christ, the same unpredictable Spirit, the same forgiving Father, and the same cloud of witnesses as every other generation.

Paul wrote to Timothy that “evil people and imposters will go on from bad to worse, deceiving and being deceived” (2 Tim. 3:13). He told the younger pastor to fight all of that, to conserve the gospel in the face of those who would empty it out.

Paul went on to say, “But as for you, continue in what you have learned and have firmly believed, knowing from whom you learned it and how from childhood you have been acquainted with the sacred writings, which are able to make you wise for salvation through faith in Christ Jesus” (vv. 14–15).

It’s important to know that you’re not crazy when you see what ought to shock every reborn conscience, what ought to break every regenerate heart.

But as for you, your anchor holds behind the veil. Weep, yes, grieve; be angered, work for reform. But don’t get cynical. Don’t get demoralized. Don’t give up.

The gospel is real. The stories are true. Christ is risen, and Jesus saves. That’s reason enough to keep standing.

How an Old Book Renewed My Mind This Week

Over the past several weeks, I had planned to reread George Eliot’s Middlemarch, but I put it aside. I had never read Silas Marner—a much less recognized novel by Eliot—and decided to read it. I was stunned by the power of it.

In the book, a weaver who grows up in a strict, legalistic Calvinistic sect in a city is falsely accused of stealing money and exiled. He finds himself in a rural village called Raveloe.

He is utterly disconnected from the people there—they don’t like the sound of his machines, he doesn’t understand their Anglican religion, etc. He ends up finding meaning in his life in the gold coins he earns from his weaving. Then he loses it all when someone steals his coins.

Through a series of unlikely events, Marner ends up adopting a toddler orphan. This is not at all a kind of “cute child makes everything better” sort of story. What changes for this man is that he doesn’t have any idea how to rear a child, and he needs the rest of the community to help him. It’s his dependence and vulnerability that causes the village to see him as a human being, to sort of “adopt” him as their own. And through this new connectedness, he slowly comes alive.

“Formerly, his heart had been as a locked casket with its treasure inside; but now the casket was empty, and the lock was broken,” Eliot writes. “Left groping in darkness, with his prop utterly gone, Silas had inevitably a sense, though a dull and half-despairing one, that if any help came to him, it must come from without; and there was a slight stirring of expectation at the sight of his fellow men, a faint consciousness of dependence on their good will.”

What jarred me was the way Eliot showed this “coming alive” through such a slow, almost imperceptible process. “Our consciousness rarely registers the beginning of a growth within us any more than without us,” Eliot writes. “There have been many circulations of the sap before we detect the smallest sign of the bud.”

Marner wants what we would today call “closure.” He tries to return, after decades gone, to the place of his old religious group to verify that they now knew who did the robbery, that Marner himself was innocent of it.

When he gets there, though, everything is gone. The chapel he once attended is now a factory, and he can find no one who even remembers anything about those days. A village woman from Raveloe comforts Silas: “You were hard done by that once, Master Marner, and it seems as you’ll never know the rights of it,” she says. “But that doesn’t hinder there being a rights, Master Marner, for all it’s dark to you and me.”

This seemed especially relevant to our present digital age. We seek to justify ourselves, to gain vindication for where we know we are, or were, in the right, and where others were in the wrong. Justice sometimes happens in a limited and proximate way, in this time between the times, but it’s never the kind of vindication we want. I have known some people who have spent an entire life trying to prove themselves—to show parents they ought to be proud of them, or a high school class back in the day that they ought to include them—and all those past presences aren’t even there anymore.

Instead of seeking to please whatever audience is back there in the past or up ahead in the future, this book reminded me that we ought to recognize what God revealed to the apostle Paul: “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor. 12:9). Or, as Jesus said to Peter, “For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it” (Matt. 16:25).

Crossing Your Crucibles

This week on the podcast I sit down with Gayle Beebe, president of Westmont College, to talk about what he calls “crucibles,” those moments of suffering or crisis that interrupt and reshape one’s life. He talks about how to find God in those crucibles, and how to build resilience and even thrive through and after them. You can listen to our conversation here.

Desert island bookshelf

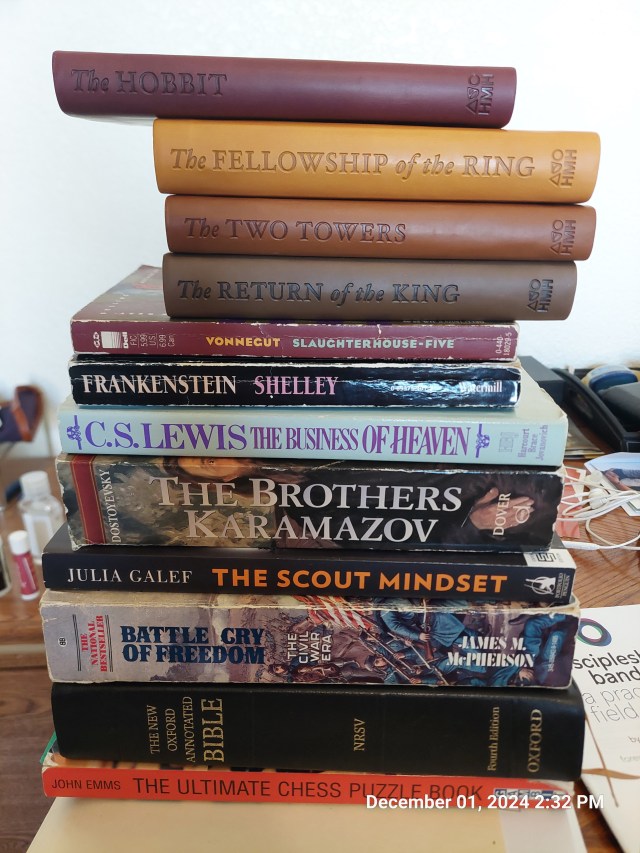

Every other week, I share a list of books that one of you says you’d want to have on hand if you were stranded on a deserted island. This week’s submission comes from reader Preston Herrington of Farmington, New Mexico, who describes himself as “a retired pediatrician whose main hobby is chess.”

He writes:

- I count The Lord of the Rings (J. R. R. Tolkien) as one book; if you want to count it as three, then this is my list of 12.

- I included my favorite study Bible, The New Oxford Annotated Bible, Fourth Edition, of course.

- Other nonfiction includes a book of daily C. S. Lewis readings (The Business of Heaven: Daily Readings) and a book of extensive chess puzzles (The Ultimate Chess Puzzle Book by John Emms).

- My favorite Civil War book is Battle Cry of Freedom: The Civil War Era by James McPherson.

- Julia Galef’s The Scout Mindset: Why Some People See Things Clearly and Others Don’t may be the book that has most impacted me in recent years.

- For fiction, nothing tops The Brothers Karamazov by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, although Tolkien’s classics are a close second.

- Frankenstein (Mary Shelley) and Slaughterhouse Five (Kurt Vonnegut) round out the list.

Thank you, Dr. Herrington!

Readers, what do y’all think? If you were stranded on a desert island for the rest of your life and could have only one playlist or one bookshelf with you, what songs or books would you choose?

- For a Desert Island Playlist, send me a list between 5 and 12 songs, excluding hymns and worship songs. (We’ll cover those later.)

- For a Desert Island Bookshelf, send me a list of up to 12 books, along with a photo of all the books together.

Send your list (or both lists) to questions@russellmoore.com, and include as much or as little explanation of your choices as you would like, along with the city and state from which you’re writing.

Quote of the Moment

“In old days there were angels who came and took men by the hand and led them away from the city of destruction. We see no white-winged angels now. But yet men are led away from threatening destruction: a hand is put into theirs, which leads them forth gently towards a calm and bright land, so that they look no more backward; and the hand may be a little child’s.”

—George Eliot

Currently Reading (or Re-Reading)

- Ben Palpant, An Axe for the Frozen Sea: Conversations with Poets About What Matters Most (Rabbit Room Press)

- Pope Francis, Hope: The Autobiography (Random House)

- John C. Polkinghorne, The Faith of a Physicist: Reflections of a Bottom-Up Thinker (Princeton University Press)

- Peter L. Berger, A Rumor of Angels: Modern Society and the Rediscovery of the Supernatural (Doubleday)

Join Us at Christianity Today

Founded by Billy Graham, Christianity Today is on a mission to lift up the sages and storytellers of the global church for the sake of the gospel of Jesus Christ. Subscribe now to get exclusive print and digital content, along with seasonal devotionals, special issues, and access to the full archives. Plus, you’ll be supporting this weekly conversation we have together. Or, you could give a membership to a friend, a pastor, a church member, someone you mentor, or a curious non-Christian neighbor. You can also make a tax-deductible gift that expands CT’s important voice and influence in the world.

Ask a Question or Say Hello

The Russell Moore Show podcast includes a section where we grapple with the questions you might have about life, the gospel, relationships, work, the church, spirituality, the future, a moral dilemma you’re facing, or whatever. You can send your questions to questions@russellmoore.com. I’ll never use your name—unless you tell me to—and will come up with a groan-inducing pun of a pseudonym for you.

And, of course, I would love to hear from you about anything. Send me an email at questions@russellmoore.com if you have any questions or comments about this newsletter, if there are other things you would like to see discussed here, or if you would just like to say hello.

If you have a friend who might like this, please forward it, and if you’ve gotten this from a friend, please subscribe!

Russell Moore

Editor in Chief, Christianity Today

P.S. You can support the continued work of Christianity Today and the Public Theology Project by subscribing to CT magazine.

Moore to the Point

Join Russell Moore in thinking through the important questions of the day, along with book and music recommendations he has found formative.

Delivered free via email to subscribers weekly. Sign up for this newsletter.

You are currently subscribed as no email found. Sign up to more newsletters like this. Manage your email preferences or unsubscribe.

Christianity Today is a 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization.

“Christianity Today” and “CT” are the registered trademarks of Christianity Today International.

Copyright ©2025 Christianity Today, PO Box 788, Wheaton, IL 60187-0788

All rights reserved.