When readers thumb through their Bibles for examples of courage, few consider flipping to the passage of the penitent thief on the cross (Luke 23:32–43). Whether in sermons or hospital rooms, his story has become a sort of byword for eleventh-hour repentance.

In contrast to his unrepentant companion, he’s seen as the poster boy for the deathbed conversion, the face of the last-minute participation prize: he is the anyone Christ can save. But what if the story of this man, whom tradition calls Saint Dismas, has more to teach us?

While Dismas’ example remains an incredible testimony of salvation in Christ, a look at details in the surrounding text reveals a deeper layer to his story—where we find not only a companion for the one who has sinned but also an example of faith and courage for the one who faithfully suffers.

We are first introduced to Dismas as he is being led away with Jesus to be crucified, likely still reeling from the shock of a beating (v. 32). Luke’s gospel labels Dismas and his companion (named Gestas, as tradition has it) as “criminals.”

But instead of using the standard word for “thief” (kleptai), Matthew and Mark use the Greek word lestes, which most Bibles translate as “robber”—that is, someone who takes goods by force—for its connotation of violence. For reference, this is the same word used in the story of the Good Samaritan for the robbers who beat up the traveler on the Jericho road.

What’s even more interesting is that the first-century historian Josephus’ use of this term suggests an additional element of opposition to Roman authority. In fact, John’s gospel uses the word lestes, translated as “rebel,” to describe Barabbas, whose crimes were insurrection and murder (18:40). Given the timing, it’s possible both Dismas and Gestas were among Barabbas’s compatriots (Mark 15:7), albeit fatally lacking Barabbas’s public relations clout and popularity.

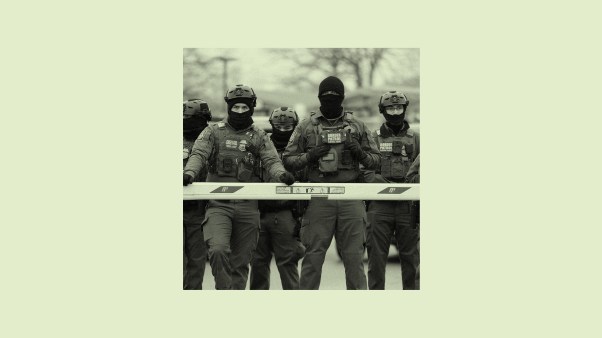

Like Jesus’ death, the two mens’ death sentences were designed to crush the spirits of both victims and observers—as crucifixion was often used against political enemies to show off the intimidating power of the Roman Empire and stand as a warning to potential imitators.

This background may explain why Dismas and his companion initially expend such excruciating effort in hurling abuse at Jesus (Matt. 27:44; Mark 15:32). Crucifixion places stress on the chest cavity, making it painfully difficult for a victim to inhale. The struggle to take each breath and deliver every curse would have made it a painful and deliberate act.

Mockery in the midst of pain suggests more than just a dark coping mechanism. These men would have grown up hearing stories of a coming messiah who would throw off Roman rule and bring justice to their people. To them, Jesus, who seemed to be nothing more than the latest in a string of pretenders, represented the ultimate failure to make things right.

Luke doesn’t tell us exactly when Dismas’ change of heart begins. Perhaps it’s the moment when Jesus spends some of his own precious breaths to ask God to forgive his enemies rather than destroy them (Luke 23:34). Maybe Dismas could sense the purpose, the sheer intentionality undergirding Jesus’ distress, so different from his own. Whatever the moment, a sense of conviction blossoms, and Dismas rebukes his fellow rebel.

“Don’t you fear God,” Dismas asks, loud enough for Gestas to hear him on the other side of Jesus, “since you are under the same sentence? We are punished justly, for we are getting what our deeds deserve. But this man has done nothing wrong” (v. 40).

This remark displays an almost shocking shift in awareness. He accepts that his sentence is balanced on the scale of justice not only with respect to the governing authorities, Rome and Judea, but also before God as ultimate judge. Despite the inhumane mode of his death, he seems to reckon with the fact that he is reaping the wages of a life lived for violence.

Perhaps even more unexpectedly, he then turns to the one many call Messiah and dares to hope: “Jesus,” he pleads, “remember me when you come into your kingdom”(v. 42).

But Dismas is not making some blind and desperate swipe at grace here. His language is that of a vassal to a king who would grant favors after taking up his reign. By acknowledging his sin and appealing to Christ’s mercy, Dismas gives up all belief in his former revolution and throws in his lot with an entirely different kind of savior.

There’s a prophetic sense to his words, too. Present-day readers may take Jesus’ resurrection for granted, but few, if any, of his first-century followers anticipated crucifixion for their messiah. In that respect, Dismas was the first person to understand and believe that Christ’s cross did not negate his coming kingdom.

At the climax of Jesus’ supposed weakness and shame, Dismas recognizes Christ’s kingly power and glory. He also appeals to Jesus’ own generosity. As Rachel Gilson notes, Dismas has the “faithful audacity” not only to believe in Jesus’ coming victory but also to believe “that the victory was won in order to be shared” even with someone as guilty as himself.

Jesus mercifully accepts Dismas’ request, albeit with a different favor than Dismas might have expected. Instead of merely responding to his request regarding a “kingdom,” Jesus promises him a place in “paradise” (v. 43). Dismas would have immediately recognized the term for the place of the righteous dead. As is his habit throughout the Gospels, Jesus offers Dismas something that includes yet surpasses the scope of an eventual earthly rule—by forgiving Dismas’ sins and welcoming him into his heavenly kingdom.

Dismas and Jesus suffer side by side on their crosses for about six hours. But as final as their last words recorded are, that is not where Dismas’ story ends.

As the sky darkens and the ground shakes, does Dismas wonder whether now is the moment for the heavens to tear and this true Messiah’s kingdom to be realized? Yet all at once, Jesus cries out and breathes his last. The ground steadies, the sun shines back through the clouds, and everything returns to the way it was before. With the main “spectacle” over, the entire crowd begins to trickle away (v. 48) As the sun begins its descent toward the horizon, all grows quiet. The kingdom isn’t coming, at least not this day.

Jesus has died, but Dismas remains on the cross for hours longer, in mounting pain. It is believed Dismas languished on the cross for at least twice as long as Jesus did. And yet as every new breath grows more difficult than the last, Dismas has the perseverance to wait for paradise. With each shudder, he clings to the promise he received, despite the clear death of its giver. I wonder if, at any point, Dismas asked himself whether the lifeless man beside him would—or could—keep his word.

As dusk draws near, soldiers come to break the ankles of both Dismas and his fellow rebel, destroying their balance and brutally cutting off their airflow to hasten their deaths, as the Sabbath was soon to begin (John 19:31–32). It probably didn’t take much longer for Dismas to die, presumably in unimaginable agony. And yet we can be sure that Dismas’ faith held on—and that his spirit endured into eternity—for Jesus is not one who fails to fulfill his promises.

What can we learn from this man’s story? Those praying for loved ones who are far from Christ can still be encouraged by the way Dismas turned to the Lord for salvation in the last moments of his life. Nevertheless, it’s important not to caricature Dismas as merely a “foxhole theist” who made a last-ditch effort out of hopeless desperation. Doing so makes light of his faithfulness and ultimately the faithfulness of the one who saved him.

In the midst of unbearable pain, Dismas clung to the promise of a kingdom that looked nothing like the one he had lived his whole life expecting. This man of action, who had relied on his physicality to further his cause, ultimately found what he was searching for when he was forced to do nothing but suffer and believe unto death.

Dismas’ endurance beyond Jesus’ death is what makes him a companion to the long-suffering. He has gone before those for whom, whether by age or chronic illness, every breath is a burden. Dismas is a brother to all those whose service to God looks mostly like waiting on his promises. In Dismas, we are reminded that faith itself is an act of courage.

His and our Savior remains the Man of Sorrows, who is near to us in our suffering—the one who is glorified even when our limbs no longer have strength. With Dismas, we reaffirm our trust that, as Trevin Wax says, Christ can “take up our burdens upon himself and deliver us from our despair.” And even in the moments when it seems Christ is absent, the promise that held the thief holds us, too.

Tori Campbell has written for The Gospel Coalition, David C Cook, and The Yale Logos.