Today, it has become almost cliché to frame the antislavery figures from 19th-century America as prophets. David W. Blight’s 2018 biography of Frederick Douglass bore the title Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom. According to Blight, a “guiding theme” of Douglass’s life was his “deep grounding in the Bible, especially the Old Testament.” Harriet Tubman has been called the “Fugitive Prophet” and Sojourner Truth the “Prophet of Social Justice.”

This habit, despite being a bit overused, is understandable. After all, some of the more extreme freedom fighters of the era saw themselves as actual prophets. John Brown, who led the raid at Harpers Ferry in 1859, believed God had called him to eradicate slavery from America. Nat Turner, who led the largest slave revolt in American history, claimed he had received divine visions. When it comes to abolitionist history, prophetic imagery abounds.

However, in Bearing Witness: What the Church Can Learn from Early Abolitionists, Daniel Lee Hill strikes a different chord. Rather than drawing on the language and themes of Old Testament prophets, Hill, a theology professor at Baylor University’s Truett Seminary, gives the movement against slavery a distinctively New Testament framing. Abolitionists, he argues, went beyond simply exposing the sins of a nation or church. They developed models of reform and renewal that can guide evangelicals today.

Hill’s goal in Bearing Witness is to “highlight and retrieve the key insights of abolitionary figures for the sake of articulating how evangelicals might bear witness to the gospel of freedom in their shared, common life.” Much of the book takes the form of a theological dialogue with three African American abolitionists: David Ruggles, Maria W. Stewart, and William Still.

Hill stresses that each of these figures understood themselves as evangelical. They attacked the institution and ideology of slavery by using what Ruggles called “evangelical weapons.” Among these weapons were Scripture, a biblical understanding of humanity, the moral law of God, close personal communities, personal piety, a willingness to bear one another’s burdens, and a commitment to preserving historical memory.

As a result, these three abolitionists offer more than examples of heroism from the past. Because their witness was so theological in nature, we can recover it not simply for inspiration but for its value in aiding contemporary movements of church reform. “What is required,” Hill insists, “is recognition, reflection, gratitude, and, ultimately, retrieval.” Alluding to G. K. Chesterton’s famous quip about tradition and intergenerational democracy, he adds, “The dead have something to say indeed. It is time we let them vote.”

We live at a moment when the precise meaning of evangelicalism is fiercely contested, with some questioning its very existence as a coherent tradition. We live, too, at a moment when critics indict the American founding itself for the founders’ complicity in slavery. In such a context, I appreciated Hill’s book for what it affirms about both evangelical and American identity.

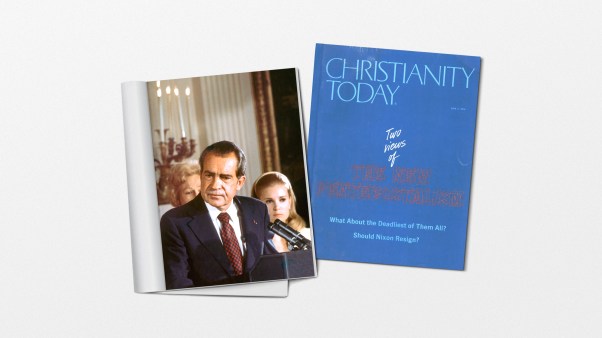

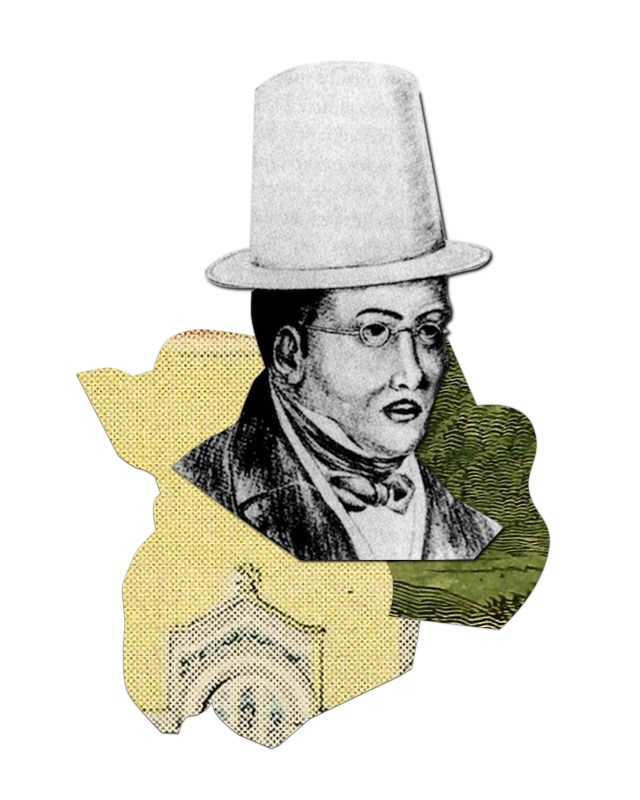

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch Tlapek / Source Images: WikiMedia Commons

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch Tlapek / Source Images: WikiMedia CommonsRuggles, Stewart, and Still were not just critics of white evangelicals, according to Hill; they were animated by a common evangelical theology. Hill states unequivocally that by drawing on these abolitionists, he is “making an argument about the very bones of the evangelical Christian tradition.”

Furthermore, their example can’t be confined within well-worn critiques of founding-era hypocrisy. By highlighting their opposition to the American Colonization Society, Hill shows that African American abolitionists understood themselves not just as evangelicals but as Americans who appealed to the Declaration of Independence and the Bible alike. To have a meaningful conversation about the nature of American evangelicalism, he insists, we must account for these oft-overlooked voices.

Hill’s book excels in presenting the “theo-political vision” of these three abolitionists. Rather than merely reporting on their views of, say, the Fugitive Slave Law, he shows how their theological convictions shaped their approach to public engagement.

Take Ruggles, for example, a freeborn abolitionist who spent most of his time advocating for and protecting fugitive slaves. In his role as founder of the New York Committee of Vigilance, he helped combat the state’s “kidnapping clubs,” which sent Black Northerners to the South in chains.

As Hill emphasizes, Ruggles applied “the long-standing prophetic principle of moral suasion” in different ways than better-known contemporaries like Frederick Douglass did. He demonstrated how enslavers violated the Ten Commandments. He appealed to God’s design for the institutions of marriage and family. He showed parallels between the social ills that prevailed in slaveholding societies and the sins condemned in Amos 2:6–7, which speaks of political, economic, and sexual injustice. And he defended the church’s purity, even invoking 1 Corinthians 5:9–11 to bar slaveholders from receiving the Lord’s Supper.

I appreciated how Hill pushes back against Ruggles’s willingness to condone collective violence for the sake of emancipation, citing Zephaniah 3:14–17 to remind us that God will fulfill his own promises. Nevertheless, Ruggles favored moral exhortation above taking up arms. As Hill notes, “Ruggles’s pamphlets and addresses” were largely aimed at “those on the margins, particularly women and freed slaves.” To me, Ruggles seemed just as revivalistic as he was prophetic. He spoke truth to power—but also to the powerless.

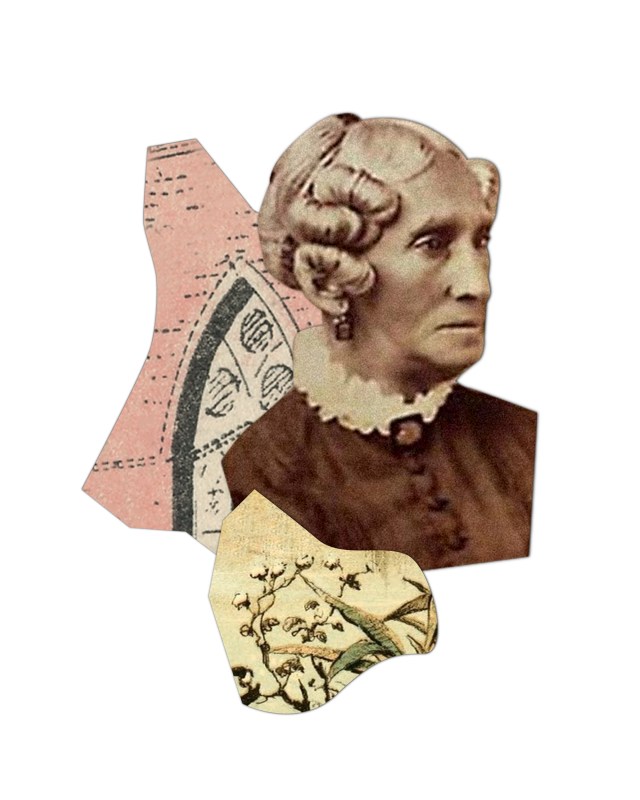

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch Tlapek / Source Images: WikiMedia Commons

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch Tlapek / Source Images: WikiMedia CommonsStewart, the second abolitionist in Hill’s triumvirate, was “one of the first women, black or white, to lecture in front of an audience of both men and women in a public space on political topics.” This remarkable woman taught Sunday school, started a school for the children of enslaved families, served as a hospital matron in Washington, DC, and became a community activist.

For Hill, Stewart offers a model for retrieving the Bible’s doctrine of humanity, particularly as it proclaims the dignity of the divine image in all people. She grounded her biblical anthropology in Genesis 1, insisting that enslaved people had been endowed with the same capacities for reason and self-government as anyone else, even if slaveholders made every effort to stifle them.

Like many white evangelicals in her day, Stewart advocated for “the creation of new institutions and communities” for spiritual and moral formation. However, for Black Americans, these communities served a countercultural purpose. Although they bore some resemblance to benevolent societies and missions organizations, these “subterranean communities,” as she called them, represented a form of nonviolent “political resistance.”

Hill’s third abolitionist case study considers William Still, credited as the “Father of the Underground Railroad” in his New York Times obituary. As a clerk for the Pennsylvania Abolition Society and as chair of the Acting Committee of the Philadelphia Vigilance Committee, Still was a paid official in the enterprise of abolitionism. Yet he too understood the importance of moral suasion, as expressed in efforts to start an orphanage, run a Sunday school, and help organize one of the first YMCA branches for Black children.

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch Tlapek / Source Images: WikiMedia Commons

Illustration by Mallory Rentsch Tlapek / Source Images: WikiMedia CommonsThough he served as an Underground Railroad stationmaster, Still arguably left his most lasting legacy as a historian. In 1872, he published his crowning work, The Underground Railroad Records, which compiled personal interviews with hundreds of individuals who passed through Philadelphia on their way to freedom.

As Hill shows, Still intended his book as more than a historical monument; it was written “in the hope that family members who had been separated would one day be able to do what he and his brother eventually did: find one another and become whole.” His historical research and preservation represented a significant ministry in itself, seeking to hold together the most basic unit of American society: the family.

If the book’s first section is an exercise in historical theology, the second section pivots toward constructive theology, asking how today’s church can live out the commitments of the abolitionists it highlights. With a host of contemporary theologians as conversation partners, Hill reflects on promoting “the public good” instead of settling for mere “ecclesial triumphalism.” Just as early African American abolitionists worked diligently to foster Christian community and “bear witness” to the life of the saving gospel, so must today’s church follow their example. Indeed, Hill observes, these spiritual forebears have bequeathed us an entire “evangelical account” for just this purpose.

The continuity between these earlier and latter sections is not always as smooth as one might expect. Hill is obviously well-versed in contemporary theology and incorporates an impressive range of modern scholars. But the book’s second section doesn’t always put these contemporary voices into clear conversation with voices from the past.

Nevertheless, in an age when we often view American evangelicalism through simplistic, nontheological lenses—whether racial, political, social, or financial—Bearing Witness achieves something commendable. From a bitterly divided period in American history, it retrieves a distinctly evangelical vision of shared gospel living that can guide the church’s witness today. Hill’s book reminds us that even the darkest chapters of the American story can yield constructive building materials for the chapters to come.

Obbie Tyler Todd is pastor of Third Baptist Church in Marion, Illinois, and adjunct professor of church history at New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary. He is the author of The Beechers: America’s Most Influential Family.