June is National Immigration Heritage Month, a time to remember the millions who have come to America from a land far, far away.

Among those millions were four children from imperial Russia.

The first, Szmuel Wonsal, was born in 1887 and made it to Baltimore in 1889, one of 11 children of a shoe repairman. Drifting through odd jobs in Ohio in 1903, he happened to watch a 12-minute silent movie, The Great Train Robbery.

Next, Israel Beilin, born nine months after Wonsal, came to New York with his family in 1892. He dropped out of school and in 1903 was homeless, earning a few pennies by hanging out in saloons and singing to customers.

Third was David Schwirnofsky, born in 1883, who became a nine-year-old newspaper street hawker. At age 15, with his father downed by tuberculosis, he became an office boy at the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company of America.

And last, Reuben Grin, also born in 1883, disembarked in Boston 20 years later and peddled used straw mattresses, sometimes carrying four at a time on his back. He eventually moved up to a wagon drawn by a horse with three legs.

Many American church members during the 1890s were not sure how to react to new arrivals like these. In 1891, Henry Cabot Lodge, a Massachusetts Episcopalian, complained on the floor of the U.S. Congress and in the pages of the North American Review about the arrival of immigrants “far removed in thought and speech and blood from the men who have made this country what it is.”

Three years later, the influential Immigration Restriction League (IRL) resolved to “arouse public opinion to the necessity of a further exclusion of elements undesirable for citizenship or injurious to our national character.” That meant keeping out immigrants except those from northern and western Europe. (Immigrants from the Russian Empire would not make the cut.)Congress had already passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, and “by 1890 abhorrence of the new immigration was spreading to wider circles.”

Yet in the same decade, social gospel pastor Charles Sheldon’s In His Steps sold tens of thousands of copies with a subtitle that popularized the question What Would Jesus Do? Sheldon ended the novel with a description of immigrants in “the depth of winter” huddled in “the thin shells of tenements” until the Holy Spirit moved Christians “to relieve the needs of suffering humanity.”

Within that range of public opinion, IRL cofounder and Harvard grad Prescott Hall was at one extreme when he sent a letter to the Boston Herald: “Shall we permit these inferior races to dilute the thrifty, capable Yankee blood … of the earlier immigrants?” Hall was a poetic eugenicist: “Already is our land o’er run / With toiler, beggar, thief and scum.” But even more-mainstream restrictionists like Francis Amasa Walker, first president of the American Economic Association and former head of the U.S. Census Bureau, also wanted to keep out “vast masses of peasantry” from “every foul and stagnant pool of population in Europe.”

Lorenzo Danford, an Ohio Methodist who chaired the US House’s immigration committee in the 1890s, may have typified the broad middle. He was willing to admit some immigrants but wanted to keep out “a class of people who have been thrown on our shores … known as the Russian Jews.” When Danford died in 1900, one congressional colleague declared that he’d “lived a Christian life [of] enlightened judgment,” and another said he was “always ready to lend a helping hand.”

But not to Wonsal, Beilin, Schwirnofsky, or Grin: All four were Russian Jews. What if anti-immigration advocates had been successful?

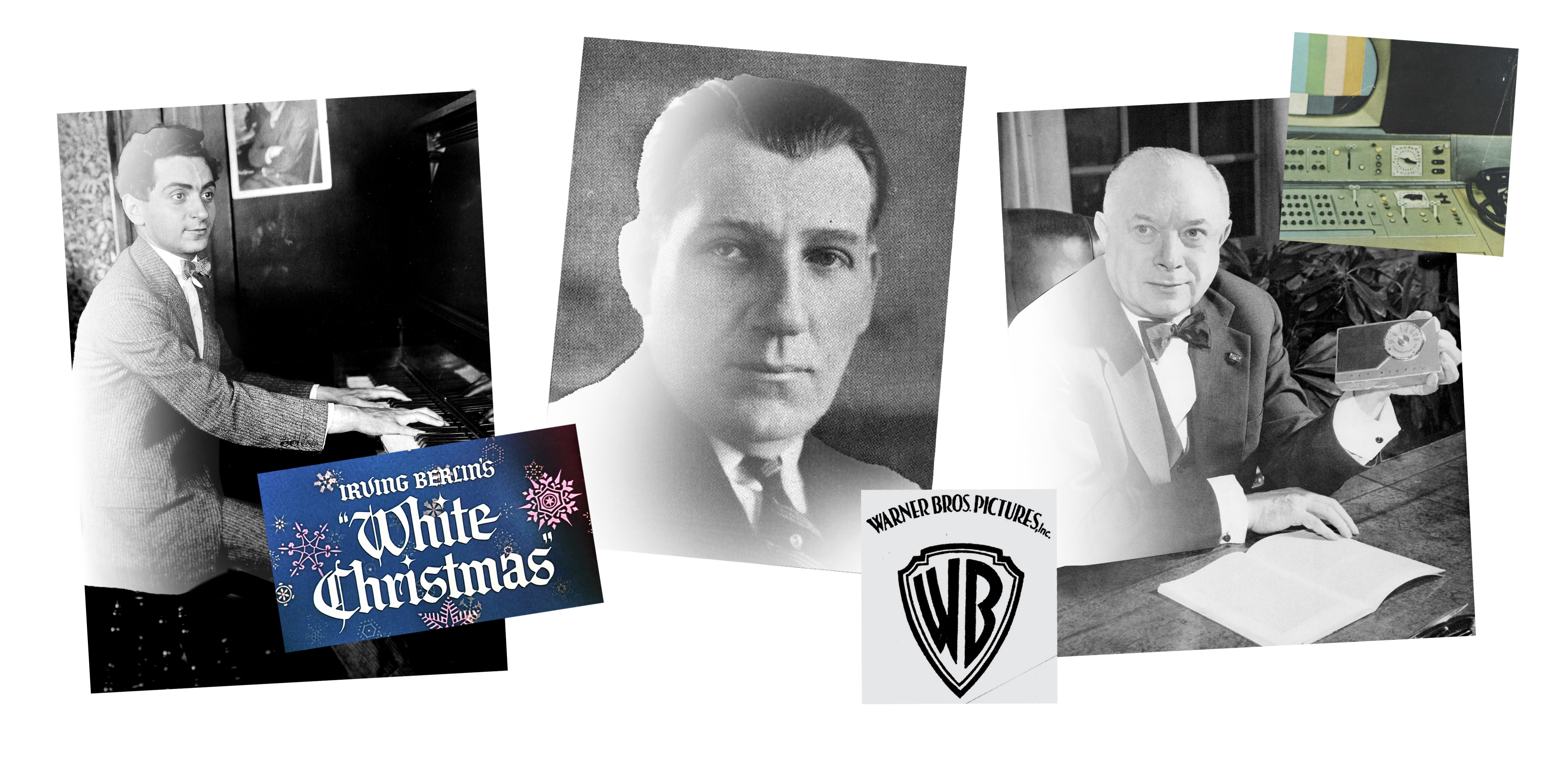

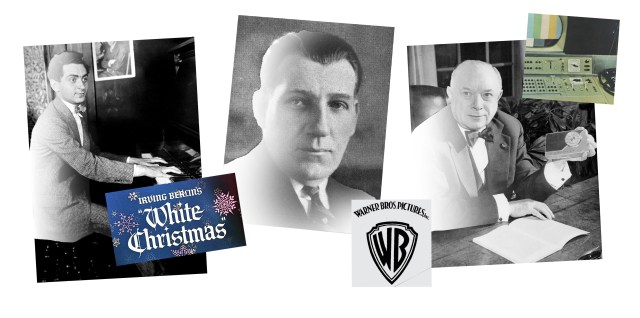

Keep out Wonsal, who changed his name to Sam Warner, one of the Warner Brothers of film history? Okay, but erase films including The Adventures of Robin Hood, Casablanca, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and The Lord of the Rings. Keep out other Jewish refugees from Russia? Okay, but erase Gone with the Wind, Singin’ in the Rain, Mr. Smith Goes to Washington, and High Noon.

Keep out Beilin, who changed his name to Irving Berlin? So be it, but erase songs ranging from “God Bless America” to “Puttin’ on the Ritz” and “White Christmas.” While you’re at it, erase George Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue and Porgy and Bess. Erase Aaron Copland’s Appalachian Spring and Fanfare for the Common Man. Erase a huge chunk of Broadway history.

Keep out Schwirnofsky, who changed his name to David Sarnoff? Early radio was point-to-point, like an oral telegraph, but Sarnoff saw an opportunity for “mass communicating” and founded RCA, then NBC—and the rest was hysteria.

Keep out Grin, who changed his name to Robert Green, and not a lot of cultural history would be erased—but I would be: He was my grandfather. He came to Boston while Joe Lee, founder of the Massachusetts Civic League, feared that “all Europe” would soon be “drained of Jews—to its benefit no doubt but not to ours.”

Illustration by CT / Source Images: WikiMedia Commons

Illustration by CT / Source Images: WikiMedia CommonsBut immigration was to America’s benefit. The year 1903 was an important one not because my grandfather arrived in a new land but because Theodore Roosevelt did, at least experientially. Up to then he’d spoken much like his friend Henry Cabot Lodge and echoed the warning in Thomas Bailey Aldrich’s poem “Unguarded Gates” about new immigrants “bringing with them unknown gods and rites … Voices that once the Tower of Babel knew!”

In September 1903, though, the New York Times headlined an extraordinary visit: “PRESIDENT STARTS ELLIS ISLAND INQUIRY Astonishes Officials by Naming a Special Commission. HE INSPECTS IMMIGRANTS Perilous Trip Through Blinding Storm.” A reporter told of how “wind increased to almost hurricane force and nearly threatened the craft. The seas ran high. … President Roosevelt was dripping wet when he dashed down the shaky gangplank of the tug and set foot on Ellis Island.”

The special commission was to scrutinize the actions of commissioner of immigration William Williams, who was in charge of the Ellis Island port of entry for immigrants. Williams wanted tough enforcement of all possible entry requirements, including turning away those immigrants with little money. Roosevelt’s traveling companions were two men sympathetic to immigrants: Legal Aid Society head Arthur von Briesen and Jacob Riis, author of How the Other Half Lives and an immigrant himself.

The Times reported a conversation among the four. Williams wanted to turn away a man who arrived with $12—the equivalent of $440 now—arguing that his authority entitled him to make this judgment call. Von Briesen said that such a decision would mean that “Jake Riis should have been sent back when he came over,” for as the Times reporter snickered, “It seems that Mr. Riis did not have as much as $12 when he arrived in America.”

An evangelical directed by his faith, Riis was a powerful influence on Roosevelt, and so were immigrants Roosevelt met during his five hours at Ellis: “A dark-haired woman tried to rush forward to the President, but was restrained, and then broke out into cries and sobs regarding the husband she might be blocked from meeting: ‘Don’t send me away from him forever! Oh, please, please let me go!’” Roosevelt “heard the woman’s sobs,” the Times reported, “and later in the day he summoned the family to the Commissioner’s private offices and held an investigation. … He thereupon made a special ruling and released the entire family.”

Whether through personal encounters or political reckoning, Roosevelt changed his immigration approachgoing forward. He quoted the Bible and told listeners, “We need to remember our duty to the stranger within our gates.” He stopped promoting literacy tests for immigrants, which would have been used to suppress entry to America just as they were used to keep Black Americans out of voting booths.

But once immigrants were admitted, what then? The Times reporter suggested an answer: Roosevelt at Ellis Island “met the missionaries who look after the spiritual and in many cases the material welfare of the immigrants.” The greeters were Protestants, Catholics, and Jews who combated anti-immigrant sentiment not only in words but also through acts of compassion. Israel Beilin and David Schwirnofsky probably received help from some of the tens of thousands of New Yorkers who volunteered at more than a thousand charitable institutions.

Their first port of call was likely Jewish organizations with names like the Hebrew Benevolent Fuel Society. But churches sponsored all-welcome medical clinics, tailor shops that provided work and produced garments for needy children, and free classes in English, dressmaking, embroidering, sewing, carpentry, printing, plumbing, and other skills.

In Baltimore, the young Warner brothers may have gained help from the Association for the Improvement of the Condition of the Poor, which in 1891, according to my research, had some 2,000 volunteers who made 8,227 visits to 4,025 families. If any little Warners became desperately sick, the Presbyterian Eye, Ear and Throat Charity Hospital offered free beds. If the Warners were cold, the Thomas Wilson Fuel Saving Society could come to the rescue: In 1890 it helped 1,500 families buy 3,000 tons of coal at reduced rates and helped 400 families buy sewing machines.

In Boston, Christians animated by In His Steps volunteered at a new social program, Morgan Memorial. Young minister Edgar Helms “was appalled at the conditions faced by immigrants who found themselves in a new country without jobs and sometimes desperate for food, clothing and shelter.” He spoke about Jesus and quoted a command: “Go thou and do likewise.” Morgan Memorial turned into Goodwill Industries.

Political and social efforts like these helped keep the immigration doors open until 1924. That made it possible for Selman Abraham Waksman, born in the Russian empire in 1888 and survivor of the 1905 massacre in Odessa of 400 Jews, to get to America as soon as he could, in 1910.

It’s good he came here too. In 1952, Waksman won the Nobel Prize “for his discovery of Streptomycin, the first effective anti-biotic against tuberculosis.” Until then TB was the “Great White Plague” due to the pallid complexion of its sufferers. Tuberculosis caused “nearly half of the deaths of people ages 15–35 in the United States during the 19th century,” not including Civil War casualties.

Charles Dickens described tubercular death in Nicholas Nickleby: “The struggle between soul and body is so gradual, quiet, and solemn, and the result so sure, that day by day, and grain by grain, the mortal part wastes and withers away. … Death takes the glow and hue of life, and life the gaunt and grisly form of death.”

Dickens called it “a disease which medicine never cured, wealth never warded off. … Slow or quick, [it] is ever sure and certain.” Certain, that is, until Waksman and his team figured out in 1943 how to stop it. Waksman’s Nobel Prize lecture describes his process of discovery, which sounds like If at first you don’t succeed, fail, fail again. Waksman said, “The first true antibiotic derived from a culture of an actinomyces was isolated in our department in 1940.”

Eureka? No: “It proved to be extremely toxic to experimental animals.” Waksman’s 1952 lecture then has pages of refusal to give up, until a real breakthrough occurred: “The conquest of the ‘Great White Plague,’ undreamt of less than 10 years ago, is now virtually within sight.” The number of US deaths from tuberculosis went from 194 per 100,000 in 1900 to 9.4 per 100,000 in 1984, a 95 percent decrease.

Improved living conditions and other medical innovations made a difference. If Waksman hadn’t connected the dots, others probably would have done so—but perhaps years or even decades later. Erase his immigration from America and you may erase thousands of lives. And how much of his determination was that of an immigrant to keep going until the Statue of Liberty was in sight?

The contributions of other immigrants from the Russian empire alone—dean of US science fiction Isaac Asimov, Maidenform founder Ida Rosenthal (formerly Kaganovich), and so many more—would make a shelf of books. You’d need a whole library to read about the value added by immigrants from Latin America, Africa, Asia, and elsewhere in Europe.

In 2015, kicking off his first campaign for president, Donald Trump emphasized the negatives of immigration: “They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume are good people.” Last year, he said of Haitian immigrants, “They’re eating the dogs, the people that came in, they’re eating the cats. They’re eating the pets.”

That’s over the top, but Trump was right to think some immigrants will bring trouble. Some evil will emerge. We cannot predict the future.

But we can learn from the past.

A National Immigration Heritage Month booklist from the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh lists 15 nonfiction works including Abdi Nor Iftin’s Call Me American: A Memoir. A reading list from the American Writers Museum has 11. Both lists include Angela’s Ashes, the Pulitzer Prize–winning memoir by Frank McCourt.

Marvin Olasky is executive editor of news and global at Christianity Today.