Living in a big city can leave me feeling almost nearsighted. My metro area starts to feel like the center of the universe, and I too easily forget the value and import of what’s happening in smaller places away from the centers of power. I suspect I’m not the only one.

I noticed that myopia anew a few weeks ago as I drove down a familiar brick road in my mother’s hometown. Decatur is a city of about 70,000 in central Illinois, known as the Soybean Capital of the World and original home of the Chicago Bears. It’s struggling. After losing 400,000 manufacturing jobs over three decades, the economy is everywhere marked by one of America’s most effective bipartisan projects: deindustrialization.

Yes, both Republicans and Democrats, influenced by big-business lobbies with “corporate myopia,” deserve credit for the situation in Decatur and many places like it all around the country. American industry went overseas, executives got richer, the middle class was hollowed out, and our sense of community waned. But at least televisions got cheaper.

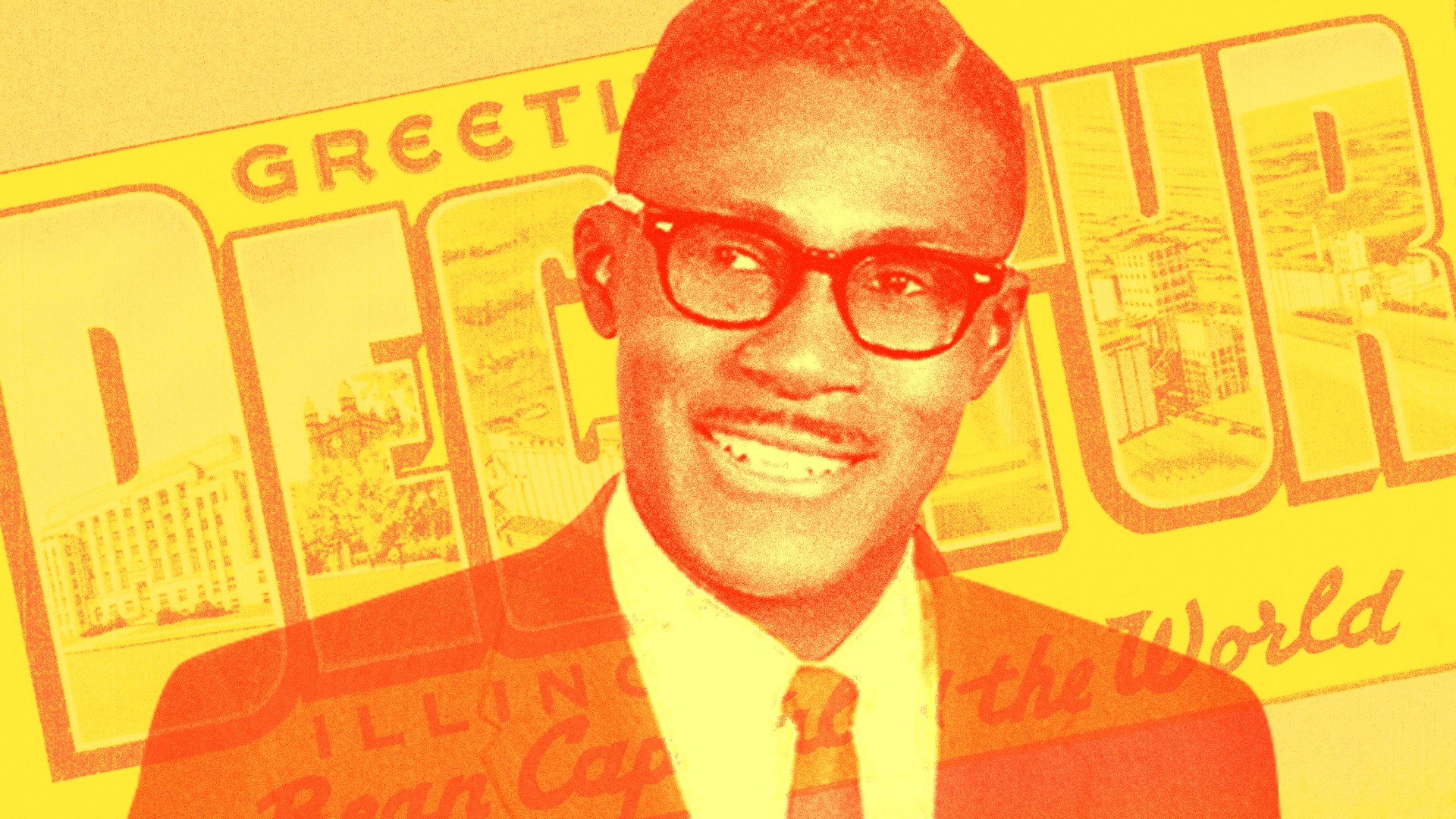

I was in town for a street-naming ceremony in honor of my late grandfather, Bishop Thomas Lee Cooper, a cleric in the Black Pentecostal denomination Church of the Living God, Pillar and Ground of Truth (PGT Nation). He served that community as a pastor and civic advocate for decades. He sought voter rights and equality in education and often worked with local sheriffs and courts to get people out of jail. Once they were out, he’d help them find jobs to rejoin society. In fact, he was called to help secure the release of Rev. Jesse Jackson from a Decatur jail in 1999.

As a child, I’d sometimes stay with my grandfather for the summer. This meant entire days in church on Sundays. On weekdays, we’d drive around town delivering groceries; visiting and praying for the sick and shut-in, as they’re still called in the Black church; and attending community events.

My grandfather was known for his energy, impatience with delayed action, and generosity beyond his means. And like Decatur, he was small in stature but dignified. He didn’t graduate from high school or run in a circle of elites, but he was wise and upright. During the street-naming ceremony, his neighbors and fellow clergy members spoke of a legacy of integrity, faith, and service.

God often blesses us with forerunners, people who come before us and sacrifice to make our lives better (Mal. 4:5–6). “Someone’s sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago,” as the investor Warren Buffet once said. These forerunners go into tough places and take on challenges for the sake of our well-being. They’re called pillars of the community because they hold us up. Even with Decatur’s economic well-being still in flux, it’s clear my grandfather was a forerunner.

He also left a special inheritance—in the biblical sense, for in the Bible, inheritance is about more than money or property. It’s also about character and a characteristic approach to life (Prov. 13:22; 2 Tim. 2:2–10). The most fruitful legacy is an intangible resource that outlives the person handing it down. It’s a legacy that guides, inspires, and gives us a standard to uphold.

We can recall Mahalia Jackson’s gospel-laden songs to guide us through trying times with a joyful outlook. The legacy of Fannie Lou Hamer should inspire a synthesis of tenacity and grace in civic engagement. The ever-astute Gardner C. Taylor’s legacy should set a standard for diligence in study and concision of speech. And looking beyond these three, if their generation could display love of enemy under the lash of Jim Crow, then we have no excuse for not doing the same today. They faced worse and did more with less.

As I preached in my grandfather’s church that Sunday, I saw my three sons and nephew watching me in the exact same pews from which I watched my grandfather and imitated his “whoop.” I realize I have an obligation to uphold that legacy of orthodoxy and love of neighbor. Squandering it under the temptations of the day would be a terrible disservice—and not only to my grandfather but also to Christ.

The truth is that we were commemorating my grandfather not based on his own merit but based on the way his life served and glorified Jesus. We were celebrating not his flawlessness but rather a life that pointed people to Jesus’ righteousness. This is a legacy we can all leave, whether we’re from big or small places.

But what happens to these legacies if we’re too unrooted to know our neighbors or if we become anonymous in large spaces?

We don’t have to romanticize small towns to admit that important things might be lost when we move from tight-knit communities to urban enclaves or their transient suburbs. We might want to think twice about trading close family ties for overpriced neighborhoods where nobody knows our names. Big-city loneliness runs deep. When the glitter rubs off of the big-city sheen, we can long for more simple and intimate spaces.

Yet we don’t have to demand everyone stay in place to acknowledge that America’s been mistaken in how it’s neglected its small towns in policy and culture.

We’ve too often made idols out of the comfort and efficiency that fuel cosmopolitan life. Yet the endless social striving in these crowded environments can impact the soul, leaving us more isolated, individualistic, and desensitized to certain kinds of immorality. Perhaps many of us go to big cities because they make us feel bigger. We might also like proximity and access to the influential and powerful with little regard for their character and impact on the community.

We’re all trying our best to be remembered and build legacies. But the Bible says, “Unless the Lord builds the house, the builders labor in vain” (Ps. 127:1). The truth is we’re all small. Our works are filthy rags, and we’re as forgettable as dust—outside our faith in the Creator and service to his kingdom.

Recent celebrity trials have reminded us how many ways people are tempted to compromise for the promise of fame and fortune. These stories should serve as a warning—a reminder to pray there’s something about us that gives people a clearer view of Jesus instead of ourselves and our weakness. As my grandfather knew well, the only legacy worth having is a mirror of Christ.

Justin Giboney is an ordained minister, an attorney, and the president of And Campaign, a Christian civic organization. He’s the author of the forthcoming book Don’t Let Nobody Turn You Around: How the Black Church’s Public Witness Leads Us out of the Culture War.