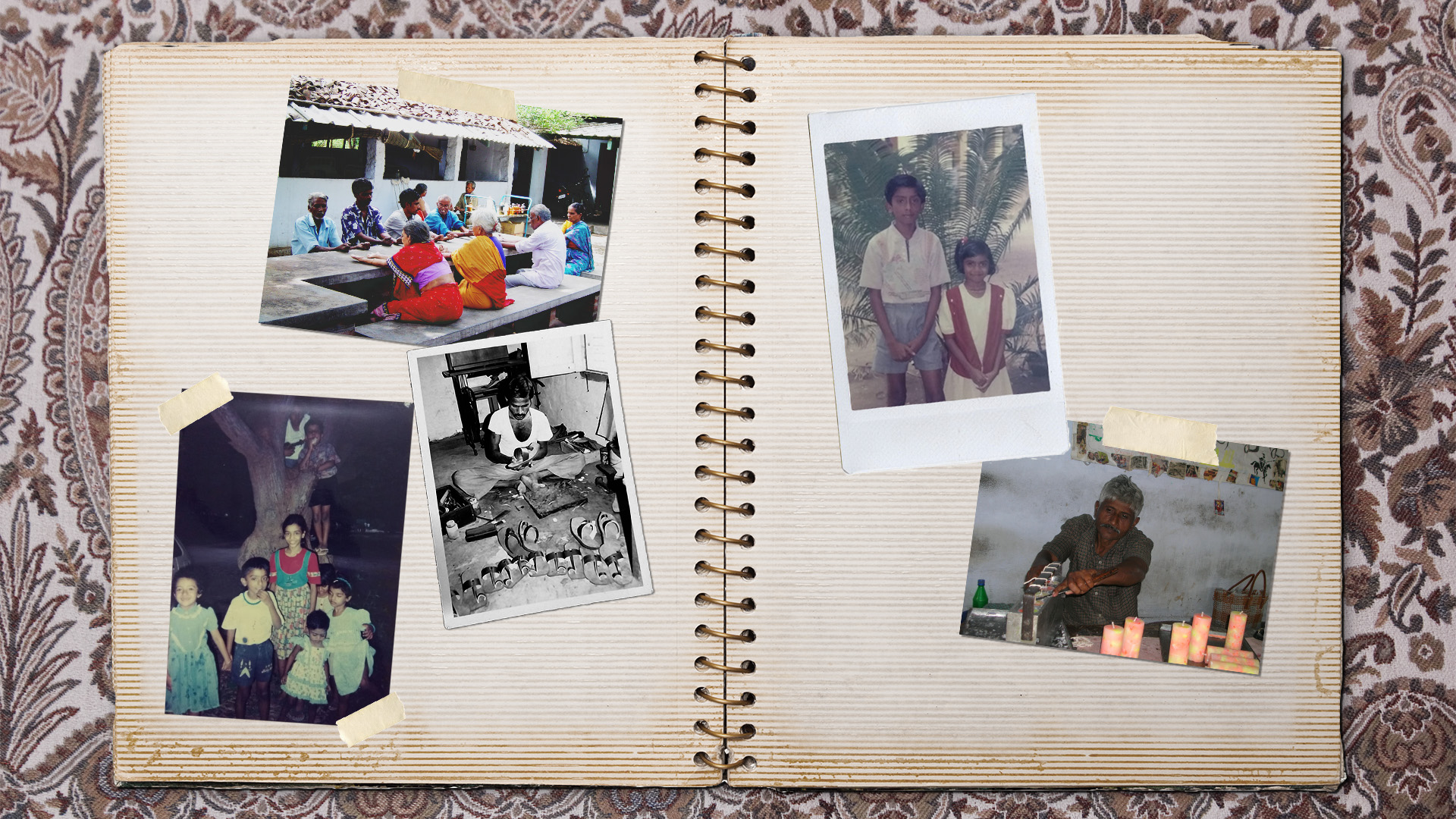

In 1994, my mother began working as a doctor at a rural hospital run by the Christian Medical College in Vellore, India. I would play elaborate games on the spacious hospital grounds with fellow neighbors’ kids and my big brother, John. We imagined that we were traveling through land, sea, and space in a rusty truck by the hospital’s parking shed, and we raced each other on bicycles.

As I played these games, I didn’t always notice the men and women who also lived on the campus grounds. Sometimes, these uncles and aunties would stop to chat with us, and I would gaze curiously at their flat noses, their missing fingers, and the crutches and wheelchairs they used to get around.

At the time, I had no clue these uncles and aunties were leprosy patients. They never mentioned their ailments but spoke affectionately to me, calling me “en rasathi” (“my princess” in Tamil) or asking, “Chellam, saptiya?” (“Sweetheart, did you eat?”).

The realization that these aunties and uncles were living with leprosy dawned on me one Sunday after church, when I saw people sitting in line by the church gate. They were dressed in tatters and held out aluminum bowls between deformed limbs as they begged for coins. Because they appeared to have leprosy, they had been sent out of their villages and had to beg for money because no one would give them work.

But the aunties and uncles I spoke with on the hospital grounds looked and felt different. Although they also lived with leprosy, they wore saris or shirts with pants or dhotis, which signified that they were well-groomed in South Indian culture. They made a living from the work they did in Ulcer Ward, the hospital’s leprosy rehabilitation center, or on the hospital campus. They did not seem dissimilar to other adults I knew. They were people whom my family and I could depend on and build relationships with.

My 16 years of living with and loving people with leprosy has taught me that healing is an inherently communal act. I learned that leprosy patients could experience belonging in loving Christian communities that could treat deep-seated emotional wounds, which medicines and surgeries are unable to fix.

At the age of five, I visited Ulcer Ward with my mom to see Karunayan Uncle, who held my foot in his paw-shaped hands, placed it on a piece of paper, and clumsily clutched a pencil between his curled thumb and index finger to draw a perfect outline. When we returned a few days later, Karunayan Uncle gave me a pair of custom-made sandals with brown leather straps and specially fitted rubber soles—something that he had created to prevent leprosy patients from injuring their feet.

Other Ulcer Ward residents provided for the medical community’s larger needs. Prakasam brought us meat and eggs every week. Balasamy swept dead leaves off the ground we played on. Many of them made candles we would light during frequent power blackouts.

But one agonizing experience helped me to understand why the people at Ulcer Ward needed us. When I was around ten years old, a pale patch appeared on my cheek. A nanny caring for my neighbor, Rahul, noticed the spot and warned Rahul not to touch me, although he disregarded her advice and told me what she had said.

“You live so close to [Ulcer Ward],” my own nanny said to me, barely concealing her aversion. “It must be leprosy.”

That evening, my mom explained that the people living at Ulcer Ward were currently undergoing treatment for or were cured of leprosy. They could not pass on the infection. But she took me to her pediatrician colleague anyway, and they found out I was mildly malnourished. After I spent a few weeks on a better diet, the patchy skin on my face disappeared.

This incident disturbed me. What if Rahul and other kids had decided to shun me? I could only imagine how the uncles and aunties at Ulcer Ward felt, knowing their families would not hug them, hold their hands, or kiss their cheeks.

As a teenager, I began noticing more of the suffering these aunties and uncles experienced. They could not feel physical pain and did not notice when they hurt themselves, so they often developed ulcers.

This was the reason behind the rehabilitation center’s name, as many who lived there had chronic ulcers that refused to heal and needed to be dressed every other day. I would imagine their wounds on my body and the pain they could not feel and pray for God to heal them.

Years later, as a doctor interning in that very hospital, I cared for the patients at Ulcer Ward. I dressed wounds, offered words of encouragement, and heard stories of hurt and hope.

More than two millennia ago, Jesus did what we put into practice at Ulcer Ward. He demonstrated that healing stigmatizing diseases like leprosy is not just about treating the body; it also requires communal restoration.

One story depicts Jesus reclining at the table in the home of a man known as “Simon the Leper” in Bethany (Mark 14:3). Simon was likely a man healed of leprosy who was once deemed untouchable in society. Yet Jesus spent time with and possibly shared a meal with him.

Another story shows Jesus declaring his willingness to heal a man with leprosy after he begs Jesus to make him clean (1:40–42). Although Jesus could have healed this man from afar, as he did for ten people with leprosy (Luke 17:11–19), he did two incredible things in this encounter.

First, Jesus touched the man with leprosy—something many people then and now would consider taboo. Second, Jesus told the man to go show himself to the priest (Mark 1:44). Upon receiving Jesus’ healing touch, the man could now reintegrate into society by seeing a priest who could pronounce him “clean” (Lev. 14:20, 31).

As Jesus’ actions reflect, a person with a stigmatizing illness requires a communal response to heal from physical and emotional wounds fully. Touching a person whom society has deemed untouchable is one of the clearest ways of saying, “I accept you for who you are.”

Much of what Ulcer Ward was like grew out of physician Paul Brand’s vision, said Anand Zachariah, a doctor at Christian Medical College who also grew up on the hospital campus. Brand, a missionary surgeon from the UK who grew up in India, discovered that people with leprosy lost their limbs because of their loss of ability to feel pain, rather than because of rotting flesh. Brand and his team pioneered and performed countless reconstructive surgeries at the rural hospital my mom and I worked in.

Brand also ensured that the rehabilitation centers he established for leprosy patients would educate them on how to care for their numb limbs as they healed from surgery. But his rehabilitation plans went beyond physical care to addressing spiritual and emotional needs as hospital staff encouraged Christians in the medical community to accept, welcome, and love the leprosy patients in their midst.

The uncles and aunties I grew up with at Ulcer Ward have since reintegrated into society. Many returned to their villages when their families agreed to take them back, and others who were unable to return because their families would not accept them now live in elderly care homes.

Leprosy is not as common in India today as it was in the past. Thanks to early intervention and rehabilitation, the disease does not result in physical disabilities as severe as they once were. Yet over half (60%) of the more than 200,000 new cases reported worldwide each year are from my country, and stigma against people with leprosy continues to persist in society, as well as within the church.

Churches in India often segregate people by language, occupation, caste, and wealth. Some churches only welcome people of one caste; in other congregations, poor people sit on the floor while the rich sit on chairs. Some Christians continue to shun people with leprosy and do not permit them to worship in the same space.

To become places of hospitality and welcome—as Ulcer Ward was for people recovering from leprosy—Indian churches can care for people who live with stigmatizing diseases as Jesus did, by having meals and worshiping God together. Churches can help people with leprosy gain sustainable livelihoods by hiring them or funding vocational training.

I live more than 900 miles from Vellore now, but I visited the city in late August and met with former Ulcer Ward patients.

Gopalan Uncle, a man in his 70s, continues to develop ulcers on his feet and finger stumps because leprosy irreversibly damaged the sensory nerves in those regions. But the staff at Ulcer Ward never treated him any differently. “They slung their arms around my shoulders or held my hands and sat next to me, chatting with me for hours,” he recalled.

Lakshmi Auntie, who is in her 50s, teared up as she recounted how her family abandoned her when she was first diagnosed with leprosy. Doctors amputated her right leg three decades ago because the ulcers on her leg kept getting infected, and she spent months bedridden at Ulcer Ward while recuperating. Today, she wears a prosthetic limb and uses crutches or a wheelchair to get around. “The staff at Ulcer Ward cared for me better than my family ever could,” she said.

As I shook their hands to say goodbye after our three-hour-long conversation, Gopalan Uncle said, “Go wherever Jesus leads you.” Lakshmi Auntie placed her hands on my head and prayed a blessing over me: “May God give you a long and healthy life, always surrounded by family who loves you.”

Ann Harikeerthan is a medical writer at Christian Medical College in Vellore, India.