Yesterday, AJ Johnson showed how new government regulations for churches in Rwanda are suppressing Christians’ ability to worship. Today, Johnson describes the pushback.

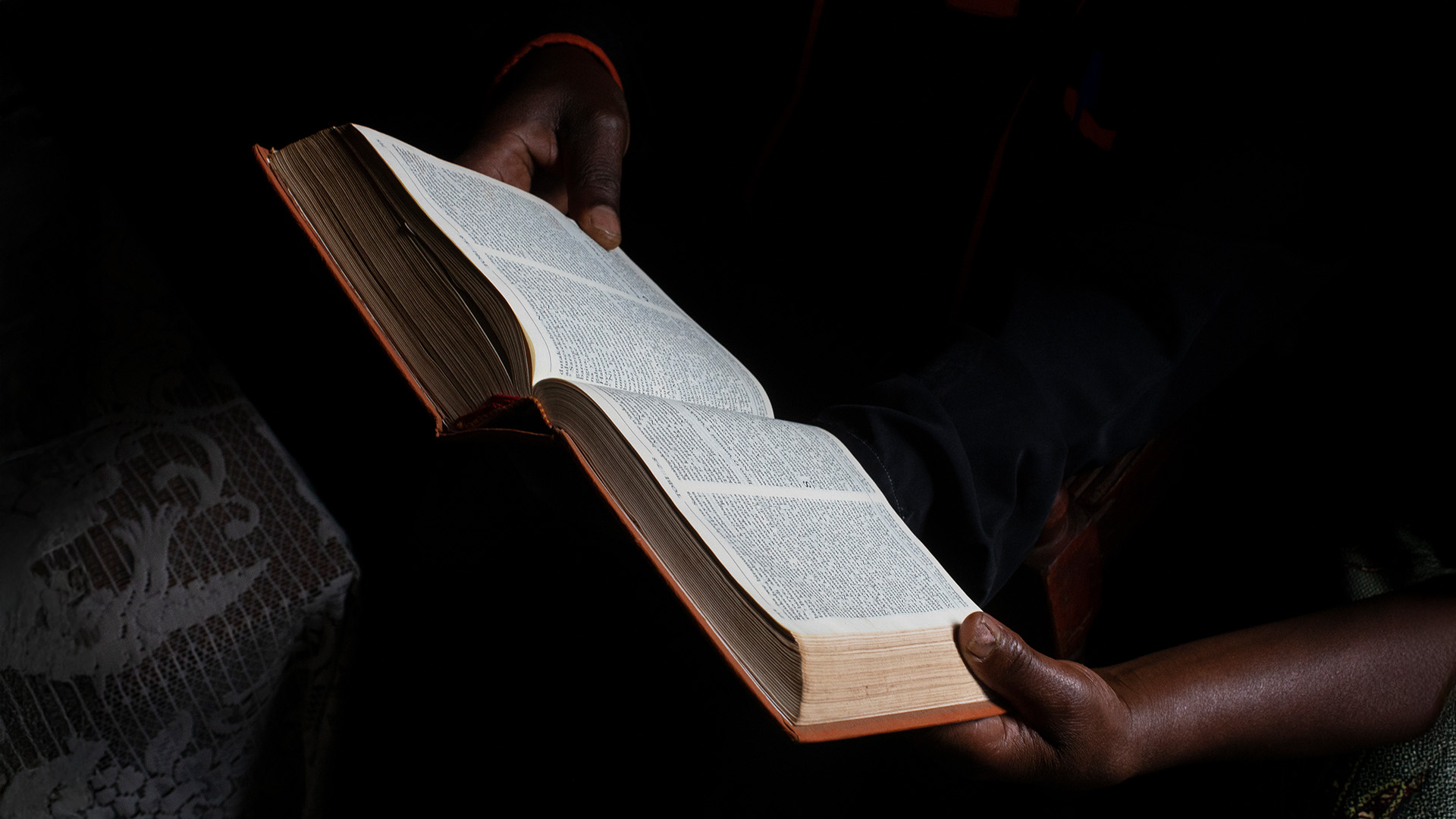

Congregations worship in the shadows. A latch clicks. Sandals shuffle over tile. When the hymn begins, it comes out more mouthed than sung so the sound won’t climb the stairwell.

More than 7,700 churches remain shuttered following the Rwandan government’s August 2024 mass inspection of prayer houses. The government’s tightening regulations have not only burdened churches and driven some underground—by requiring extensive pastoral training and inspecting church facilities from toilets to noise levels—but also produced a chilling effect on pastors’ speech.

Despite the risk of retaliation from the government, some Rwandan pastors are pushing back against the new rules. CT has agreed to change or withhold some church leaders’ names for their protection.

For rural pastors, the reforms are simply untenable. “In Kigali, you have neighbouring communities that would be affected by the sound coming from a church but in Kagera, there is a church up in the mountains so there are no neighboring homes. The congregants don’t have cars or even motorbikes so the issue of parking should not be a requirement,” said pastor Kabagambe Nziza of New Life Bible Church.

Rural churches can’t gather enough local signatures in support of their congregations. “Why demand 1,000 signatures? Are churches political parties?” interjected another pastor, whose name CT agreed to withhold to avoid reprisals.

Human rights groups amplify these cries. The World Evangelical Alliance submitted a report to the UN in July calling the Rwanda’s church regulations contrary to the country’s constitution and “not in compliance with international human rights standards.”

A February report by the Christian organization Open Doors says these regulations derive from a “dictatorial paranoia,” a dominant persecution engine in Rwanda, with the government exerting significant control over religious institutions and practices.

The closures are not just spiritual. They rip at Rwanda’s social fabric.

Beyond their role as centers of worship, churches serve as hubs of trauma care and community healing. More than 64,000 Rwandans have participated in Mvura Nkuvure, community-based sociotherapy led by faith groups, to walk toward trust and shared dignity.

Participants say the therapy builds safety, trust, care, and respect between former enemies. Survivors and perpetrators meet through church-led reconciliation forums to listen and forgive, a process many describe as restoring not just emotional wholeness but also the bonds of community life, Catholic News Agency reported. An academic review in 2024 confirmed churches and faith-based institutions fill critical gaps in mental health care in Rwanda, supporting survivors of conflict with culturally attuned, accessible care.

Without churches, neighborhoods lose job training, counseling, orphan aid, and loans. Kamanzi, the pastor from the previous article, stacks chairs after a service. “Churches are not just about preaching. They are places of healing and community,” he said. Now underground gatherings fill the void, but fear lingers: “We try not to sing too loud.”

In late July, a group of evangelical Rwandan pastors and ministry leaders started quietly working on a draft position paper proposing adjustments to the current regulatory framework. Although they haven’t formally published it out of concern for safety, the document reflects a growing but cautious internal push for government reforms. The position paper’s key proposals include reinstating the five-year compliance period for branch leaders, removing the 1,000-signature quota in rural zones, accepting modular or informal theological training for pastors, and exempting churches already approved in prior inspections.

“Regulation is not evil,” the draft reads. “But it must be humane, equitable, and anchored in dialogue.”

So far, the position paper’s writers have issued no official communication, nor has any government response indicated such a paper has been submitted. Authors of the document have refrained from identifying themselves publicly, citing fear of reprisals.

In a rural village, another pastor leads prayers in a mud-walled barn. Her congregation, too poor to soundproof their building or pay the fees, kneels on dirt floors, their whispers mingling with the rustle of maize stalks outside. “These rules are for cities, not us,” she said. “But we won’t stop worshiping.”

Her defiance reflects a broader struggle.

Rwanda’s rigid, one-size-fits-all regulations, shutting down thousands of churches and mandating pastoral credentials, stand out. Still, they echo a broader African trend of governments tightening control over religion, often lumping genuine faith communities together with rogue operators with sweeping rule changes.

In Kenya, a task force convened after the Shakahola starvation cult and proposed requiring theological certification and a state registry for pastors. In 2023, the doomsday cult led by Paul Nthenge Mackenzie compelled followers to starve themselves to “meet Jesus,” an instruction claiming more than 400 lives, many of them children. Authorities recently found five more bodies at nearby gravesites, raising the number of suspected burial locations to 27. The fallout prompted fierce debates about how to prevent religious abuses. One task force recommended the state impose more regulations. Some evangelicals have resisted, fearing politicization and threats to religious freedom.

In Tanzania, the government shut down the church of politician Josephat Gwajima after he accused the state of human rights abuses. Equatorial Guinea issued a decree mandating all religious bodies re-register or risk closure. In South Africa, new data-privacy laws have raised compliance concerns for churches sharing member photos or testimonies online.

Though these efforts vary in origin, some triggered by abuse, others by suspicion or strategy, they reveal a regional trend toward the formalization, filtration, and at times frustration of religious expression. These uniform policies, meant to weed out predators, often ensnare humble worshipers, driving devotion underground as they fail to distinguish between the faithful and the fraudulent.

Rwanda’s broad regulations have turned sanctuaries into secret gatherings. Rural pastors like Nziza face the same demands as urban megachurches. The 1,000-signature rule alienates small congregations, forcing thousands to worship in secret. This rigidity, critics argue, sacrifices spiritual freedom for bureaucratic control, silencing the very communities it claims to protect.

Back in his house, as twilight falls over the Kigali ridge, Kamanzi pulls a white candle from a drawer and places it on the windowsill.

His youngest son, tugs his sleeve. “Papa, when will we go back to church?”

Kamanzi kneels beside him, his eyes fixed on the flickering flame.

“Soon,” he whispers. “But until then, we worship here.”