When news broke last month that ICE had detained more than 300 Korean nationals at a Hyundai plant near Savannah, Georgia, Christina Shin took a break from posting reviews of beauty products and irreverent slice-of-life videos on TikTok to address the issue of immigration.

Shin criticized the raid and the Korean American Christians who used the catchline, “Illegal is illegal” to defend ICE’s right to enforce the law.

“We are privileged that our parents got here legally, got the paperwork, made us [to] be born in the States,” Shin says into the camera, speaking to second-generation Korean Americans who take a hard line on immigration. Shin, a 35-year-old office manager in Atlanta, said she is not affiliated with any political party, but seeing the callous responses from some of her fellow Korean American Christians made her “blood boil.”

“It doesn’t seem like they have any empathy for their community members,” she told CT.

Still, when she went to her church on Sunday, she chose not to talk about the raid with her friends and fellow parishioners. She attends a 200-person Korean-speaking ministry for young adults that is part of a larger Korean church outside of Atlanta.

“I don’t want to be the one causing drama and stuff, especially at a church discussion where we’re trying to love each other,” she said.

Highlighting the sensitivity of these topics in immigrant churches, Shin asked that her church not be named.

The September 4 raid at an electric vehicle battery plant co-owned by South Korean companies Hyundai Motor Group and LG Energy Solution was the largest single-site operation by US immigration authorities.

Images of workers handcuffed at the Savannah plant and reports that they faced poor conditions in the detention center spread across social media, causing panic and confusion among Koreans both at home and abroad. US Homeland Security stated that those arrested had overstayed their visas or had entered the country illegally, although some workers disputed the claim.

The operation came on the heels of several other cases of ICE apprehending Koreans in the US. In June, ICE arrested Justin Chung, who had served a commuted sentence for murder in 2007, while he was in the process of complying with deportation orders, according to a Korean American advocacy group.

Then in July, ICE took Tae Heung “Will” Kim, a 40-year-old PhD student and green-card holder, without explanation or access to a lawyer. Authorities later pointed to a 2011 drug charge. In August, faith leaders successfully rallied for the release of Yeonsoo Go, a 20-year-old undergrad at Purdue University and daughter of an Episcopal priest, who was arrested after a visa hearing and held at a Louisiana facility.

In South Korea, anger toward the Hyundai-LG raid united conservative and liberal lawmakers, even as right-wing supporters of the impeached president Yoon Suk Yeol borrowed language from the MAGA movement. Within a month, the US eased restrictions on South Koreans working in factories like the one in Georgia.

In the US, Korean American Christians have had mixed reactions to the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement tactics. While some emphasize the importance of upholding law and order, others, like Shin, argue that such views overlook the hardships that immigrants face.

Many churches have stayed silent on the issue, seeking to protect undocumented members and to preserve unity among congregants who hold differing political views. At the same time, organizations like the Korean American Sanctuary Church Network continue to offer legal services, financial assistance, and shelter to immigrants in need.

“We should take care of the weak and the people who are not privileged enough to go through the right process,” Shin said.

About 110,000 unauthorized immigrants from South Korea live in the US, according to a 2022 report from Pew Research Center. While the earliest waves of Korean immigrants were primarily laborers, victims of war, and political refugees, the US saw a surge of white-collar workers from the 1960s through the 1980s driven by high unemployment and political instability in South Korea. Today, the Korean American population numbers 1.8 million, with more than one-third identifying as born-again or evangelical Protestants.

For many Korean Christians on the right, sympathy for immigrants is separate from the principle of fairness in the justice system.

“A crime is a crime, but that does not mean that I’m less compassionate on the person,” said Samuel Shon, 34, a small business owner and deacon in Fairfax, Virginia. For Shon, abiding by the law is a way to honor God. However, he said his faith calls for empathy toward those who were not born with citizenship.

“I feel for them, because they’re just trying to do what’s best for their family, for their individual selves,” said Shon.

Shon’s parents immigrated from Korea to the US in the 1980s and started out as street vendors before working their way up to own several businesses. At the time, US immigration policy favored family reunification and skilled laborers, causing Korean-born immigrants to become the 10th-largest immigrant group in the country.

For Shon, following legal pathways to US citizenship, however challenging, is a prime example of biblical submission to authority. “I don’t think it ought to be an easy process. It should be difficult, much like citizenship in heaven … that was bought with a price,” he said.

In Los Angeles, James Chae, 42, knows just how difficult the immigration system can be. His wife, a Korean national, waited seven years for US citizenship. Though Chae, who identifies as center-right, supports reforms to make the system more efficient, he said existing immigration laws should be enforced in the meantime, pointing to concerns over crime and national security.

“My heart goes out to them,” Chae said of the undocumented people in his city. “What would Jesus do? I’m sure he would have open arms … [But] in the world we live in today, it’s really hard to do what we think Jesus would have done.”

Even though Trump’s immigration policies affect many Korean Americans, pastors and congregations often stay apolitical and dispassionate at church.

Raymond Chang, a pastor and the president of the Asian American Christian Collaborative, noted that one reason is because some pastors don’t want to draw attention to vulnerable undocumented congregants. This is especially relevant as, in January, the Trump administration rolled back protections that prevented federal agencies from making arrests at churches and schools.

Pastors also face internal division. Like many religious leaders across the country, some Korean American pastors said they’ve faced criticism from parishioners for speaking too much about current events. Some said long-time members of the church have left over political disagreements.

“There’s a lot of … churches that are trying to figure out [how to] disciple people in the midst of all the political division that we’re seeing?” Chang said. “The conversation is so polarizing and toxic and loud.”

Justin Oh, 26, of Long Island, once believed pastors should avoid politics entirely. “Those are secondary things, and obviously the most important thing is preaching Christ,” he said.

But after seeing an increase in divisive political content on social media, especially rhetoric demeaning certain groups of people, Oh’s view of the church’s role has evolved. “For us to just stay silent, I don’t think that’s right,” he said.

Oh noted that the Korean Christian community tends to not engage on immigration issues publicly. “We live in a bubble. We just stick with each other and pretend as if nothing else happens,” he said.

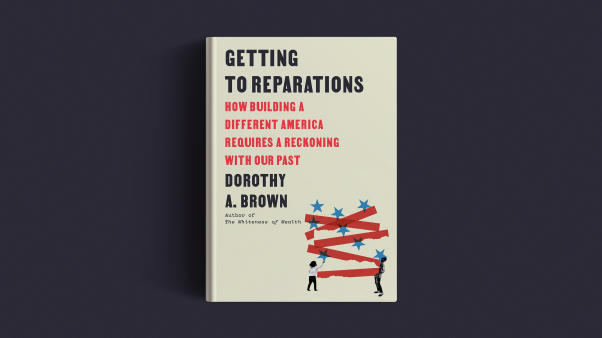

For Mina Song Lee, 25, a theology student in Atlanta, this passivity highlights a dissonance within the Korean American church. Historically, the church has been the central institution for immigrants to the US, offering practical aid and standing against racial discrimination. Many pastors started Korean American churches with ministries for new arrivals in mind.

“There are resources within the Christian tradition that are incredibly liberating, incredibly healing,” Lee said. Yet growing up in a Korean Pentecostal megachurch in New York City, Lee, a registered Democrat, saw little focus on social organizing. She described a culture where faith was personal, not political. “Our theology doesn’t compel us to be political actors,” said Lee.

She enrolled at Emory University in hopes of understanding how that apolitical posture developed. In Atlanta, Lee volunteers with church-run fundraisers and food drives to support the local migrant population—and hopes for more dialogue and action from the Korean community in the future.

Some advocates say they are beginning to see a shift in how Korean American churches are responding to immigration issues. After the Hyundai-LG raid, more first-generation Korean American churches in Georgia opened their doors to host Know Your Rights trainings, sessions designed to prepare people for encounters with immigration authorities.

Grace Choi, head of the New York chapter of the Coalition of AAPI Churches, said the move was unusual among Korean faith leaders who have long resisted anything in the public sphere, including nonpartisan voter registration drives.

“[The raid] is sparking another level of engagement with churches,” Choi said.

More churches are also interested in working with the Korean American Sanctuary Church Network, which was formed in 2017 in response to the anti-immigrant rhetoric of Trump’s first campaign. Today it includes 150 churches across the New York metropolitan area and Chicago.

Initially, some congregations were opposed to working with the network, but that’s changing, said Youngsoo Choi (no relation to Grace), head of the organization’s legal task force: “They understand how important it is to have such organizations [on] their side in this challenging time.”

The network partners with immigration attorneys, community advocates, and faith leaders to offer legal support and spiritual care to the Korean immigrant community. Earlier this year, it held legal seminars at nine local churches over a two-month period.

Even as some churches are more willing to engage on immigration issues, for Korean American congregants like Shin, the decision to publicly voice their opinions is a fraught one.

Shin’s TikTok has returned to its lighter fare, and she remains cautious about sharing her views on immigration at church. Still, she recently brought up the issue during a dinner with her small group, warning that “if ICE really wanted to, then they could hit up all the churches.”