From July to September, Darmali Ismail and the 80 other people sheltering at his church—Episcopal Church El Fasher in North Darfur, Sudan—survived on one meal a day. Some days they didn’t eat anything.

The group, made up of the church’s congregants and members of the local community, included 30 children between the ages of 3 months and 12 years. When they heard the approach of the raiding paramilitary group, Rapid Support Forces (RSF), they would hide under the church’s plastic chairs.

“We were feeling stuck and sad,” Ismail said. “Each day was a battle for survival.”

Intensified fighting between RSF and the government-backed Sudanese Armed Forces (SAF) in El Fasher has displaced Ismail, his congregation, and at least 80,000 people in North Darfur’s capital in recent months.

Around noon on September 14, Ismail heard distant gunshots. As he listened, the crack of gunfire drew nearer.

Three trucks carrying dozens of RSF members arrived, along with more armed forces on foot. They shot at the church building as Ismail and his members fled. “We didn’t even know where we were running to,” he said. RSF kidnapped two male members of the church. They killed one, a 25-year-old. The other escaped.

“The church was usually a safe place,” Ismail said. “But not anymore. No one is safe.”

Churches have served as makeshift shelters for many of the country’s displaced residents since the RSF and the SAF began fighting for control of the country in April 2023. Soon RSF began attacking churches and eventually hospitals.

After seizing full control of El Fasher in late October, RSF used drones to bomb Saudi Maternity Hospital, the only functional hospital in the city, killing more than 460 patients and health workers.

RSF has used drone strikes against hospitals, displacement shelters, power plants, and marketplaces to gain an edge in its bid to drive the government’s army out of its last stronghold in Darfur. After the takeover, Al Jazeera reported widespread atrocities, some filmed by RSF fighters and posted on social media.

“The RSF have thrown away every proper way of conduct,” said Tom Catena, a physician at Mother of Mercy, a Catholic hospital in the Nuba Mountains. “We are certainly a target. I don’t think that there’s any doubt that we are liable to be hit. We are not protected.”

The World Health Organization condemned the killings and said the RSF’s attacks on civilian care centers in El Fasher have left more than 260,000 people trapped with “almost no access to food, clean water, or medical care.”

In October alone, the RSF killed an estimated 2,000 unarmed civilians, with reports of mass executions, sexual violence, and widespread looting. Since the war began, the fighting has killed an estimated 40,000 people and displaced 12 million, making it the largest displacement crisis in the world, according to the UN refugee agency.

President Omar al-Bashir originally formed the RSF in 2013 to combat Sudanese rebels. He later extended its service to border control and deployed the group for foreign conflicts in Yemen. Then, under the leadership of Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (also known as Hemedti), a military officer and politician, the RSF evolved into a formidable militia with ties to Russia.

Bashir saw Hemedti as his protector, but then the warlord turned on him. In April 2023, the now-powerful RSF seized parts of the country, including El Fasher and the capital of Khartoum. The RSF’s clash with the Sudanese army sparked a civil war.

Earlier this year, the army forced the RSF’s retreat from Khartoum. But Hemedti vowed a “stronger, more powerful and victorious” return, rejecting negotiations with the government in favor of “the language of arms.”

The RSF’s attacks aren’t just about power—they tie into ethnic and religious motivations as well. The RSF, predominantly Arab and Muslim, often targets non-Arab and Christian communities to commit acts of violence or seize property.

Nonprofits reported the RSF has vandalized 165 churches and turned others into military bases.

Saman Farjalla, the Episcopal bishop of Wad Medani Diocese, told CT the RSF has occupied several of his churches, storing cars and weapons on the premises and living in the buildings.

Farjalla said the RSF has looted churches, including St. Paul’s Cathedral in Wad Medani: “Only the building is still standing. Everything inside is gone.”

He added that church members now meet in temporary locations for prayer and worship. The region’s instability makes it difficult to reach scattered church members.

“Destruction is happening everywhere,” he said.

Mohamed Ismail (no relation to Darmail Ismail), pastor of Baptist Church Mayo in southern Khartoum, was forced to abandon his three-year-old church after militants looted the building.

“We lost everything,” he said. “But the worst is that we have no means to get in touch with our members. It has been so painful.”

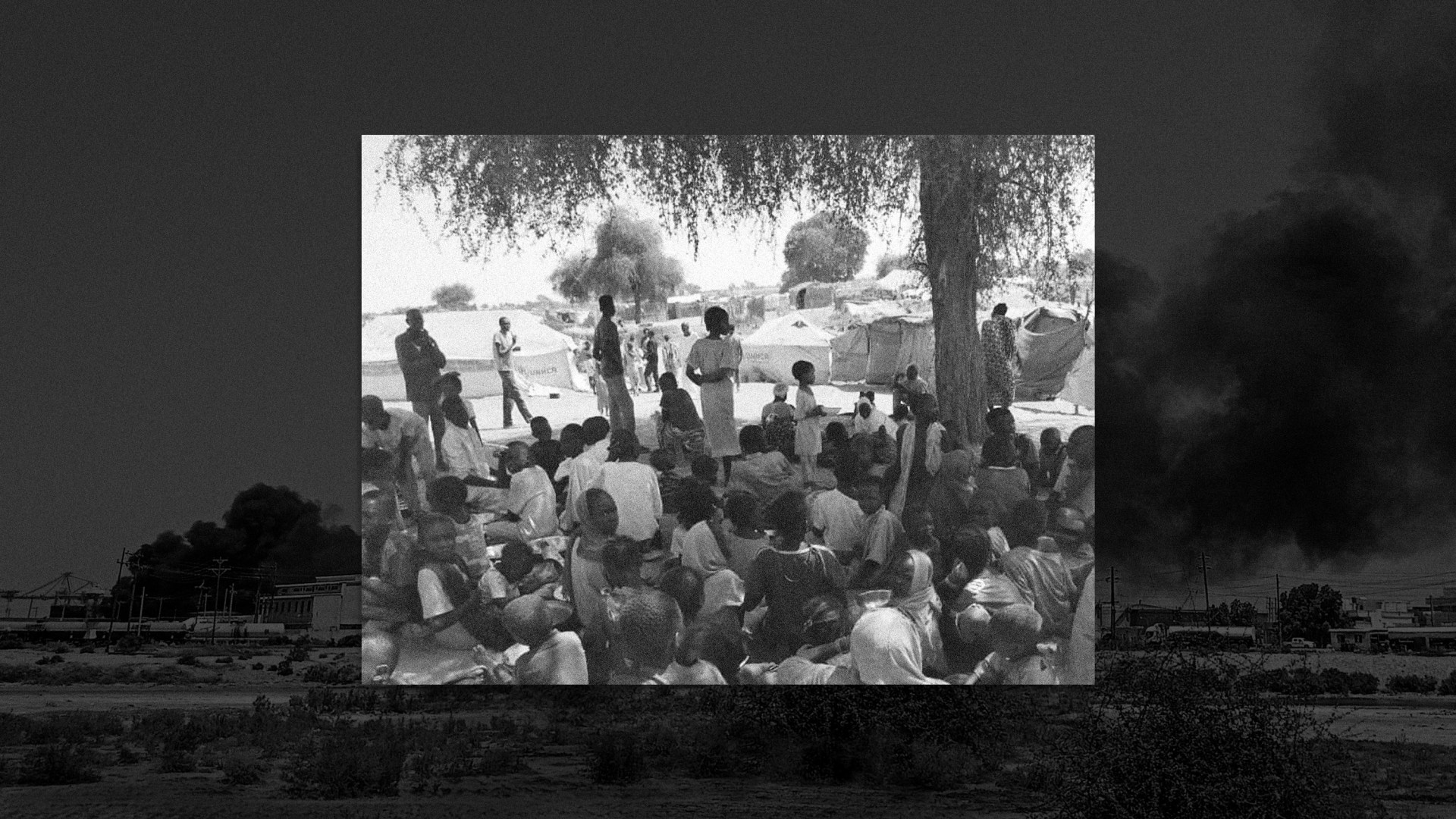

After fleeing the RSF in September, Darmali Ismail and the group sheltering at his church headed to Abu Shouk camp, about four miles away from El Fasher. They slept under trees and in empty houses while continuing to dodge bombs and bullets, Ismail said.

“I was not feeling that I would be alive until now,” Ismail said. “I was thinking, They will shoot me now. I will fall soon.”

As the bombing increased, Ismail’s group walked 18 hours to Tawila, a town west of El Fasher that is now controlled by the Sudan Liberation Army, a neutral force in the conflict. Thousands of displaced Sudanese occupy the town, including 117 Christian families who sometimes join Ismail in his daily prayers under a desert date tree. Sometimes they eat together too—still just one meal a day.

The winter nights are cold, and Ismail said they don’t have blankets. Most people sleep under the trees. They spend most days waiting, with no jobs or schoolwork to break up the grinding boredom. If people get sick, they can’t get to the nearest hospital, which is 55 miles away.