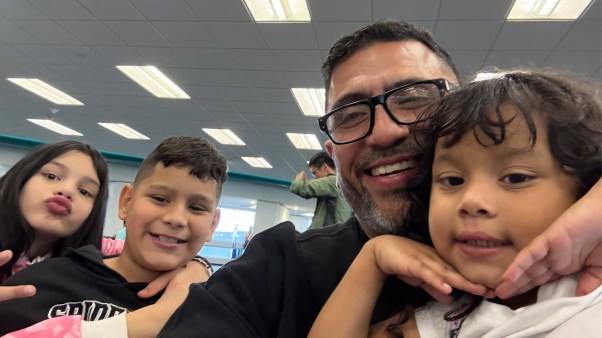

Since federal agents arrived in Minneapolis under direction from the Trump administration to arrest and deport illegal immigrants, protestors have responded with vigor to what they perceive as an invasion of their city and unlawful actions by ICE agents.

From individuals like Renee Good and Alex Pretti who engaged on city streets with federal agents to the group of protestors who interrupted a worship service at Cities Church in St. Paul, locals are expressing their distaste for the administration’s methods using a variety of tactics. Some track and report ICE movements and actions in neighborhoods. Others meet federal agents with signs, whistles, and chants. Still others gather food to distribute to immigrant families afraid to leave their homes.

To better understand the protests of recent weeks, The Bulletin sat down with pastor and political strategist Chris Butler, who directs Christian civic formation at the Center for Christianity and Public Life. Here are edited excerpts of their conversation in episode 245.

How would you describe what you saw at the protest at Cities Church?

Chris Butler: As an organizer and somebody who’s participated in lots of protests, I saw a bad protest action. Creative protest is an important part of our political culture, but this seemed like a tactically and morally bad action.

Russell Moore: I’m not sure how the leaders of this protest wouldn’t have said this action was at least counterproductive; and I would probably agree with them about the shooting of Renee Good, the actions of ICE in Minneapolis. But this was not a well-chosen way to express that. It actually hurts the cause of drawing attention to Renee Good.

Interrupting worship would always be a bad strategy for protests, but that’s especially true when you’re dealing with a time when we’ve had church shootings. At the end of it, we knew what was going on, but nobody would’ve known that at the moment. That’s not a way to decelerate and cause people to actually think reasonably about how we get justice in Minneapolis.

The pray-in movement during the Civil Rights Movement was a very different kind of protest. The pray-in movements said, “We’re going to participate in worship and pray.” The disruption actually happened from the churches that were attempting to throw them out.

What are the appropriate boundaries for protesting?

Butler: A lot has been lost in our protest and justice culture. I started organizing and doing justice work as a 12-year-old, and I’m grateful for the chance I had to learn from senior citizens and folks who were much older than me.

A protest action has to be part of a larger process for justice. First, you have to be really clear about what you’re trying to achieve. The goal should be to achieve some kind of concrete improvement in people’s lives. If, for example, we’re trying to de-escalate ICE action in Minneapolis, that needs to be the goal, not just to bring attention to my group because we want the attention.

Then, there are steps in the process. Martin Luther King in his 1963 “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” lays out the process well. He talks about gathering the facts and making sure that there is injustice. Then there’s a step of negotiation and the process of self-purification. If you’re a Christian doing this, that language works well. Even in secular environments in the old days, there was a lot of training and thinking that went into an action. Whatever action we do needs to encourage empathy, not fear; so there’s a lot that needs to come before direct action.

Moore: Dr. King was right about the process of this. He’s also right in saying to the ministers in Birmingham, I’ve spent time talking about the fact that we cannot carry out moral objectives with immoral means. The reverse is true also. You’re going to have people always looking for where the inadequacy is in the way that people are protesting. Because of this, make sure that you are carrying out that protest in a way that is both personally moral and that is actually addressing the consciences of those you’re trying to address. This didn’t do it.

Butler: If you call a news reporter and say, “Hey, we’re going to pick up the phone and call this church down the road and talk to them about this pastor on their staff with whom we have a conflict,” news reporters aren’t going to show up. That’s not going to get clicks or be on social media. Sometimes, you can get things done in ways that don’t attract social media but win improvements for people in their lives. You want to start in those places. If you can accomplish that without disrupting other people’s lives, then you should.

How do you gauge the effectiveness of a protest?

Butler: You have to wait to see the effectiveness of a justice campaign; but the actions that we take, especially when you’re doing direct action, should begin with a goal in mind. For example, your goal might be that a congregation signs a letter rebuking the ICE office. Without a specific goal, it becomes really hard to tell whether a protest was effective or not.

When you think through the direct action that you’re going to take, you have to ask yourself, How are we going to apply pressure to this person who can give us what we want, in a way that’s actually going to get them to give it to us? Oftentimes, antagonizing that person in outlandish ways won’t get that done. This process creates accountability for us. Way more things are involved in the process of direct action than just showing up in a place and doing a thing. Too many times, in lots of different protest situations that I’ve been privy to in recent times, folks are not taking that robust approach. It’s much more reactionary.