It was the coldest night in years for Minneapolis, but a young refugee’s friends there texted that they wanted to him to come hang out.

He texted them back that he couldn’t come because his dad didn’t want him going out. Even as legal refugees, this Afghan family, whose identity is withheld for their safety, was concerned about ICE (Immigration and Customs Enforcement). The young man’s mom poured more saffron tea for everyone at their home as they sat on cushions and talked with friends who had come for dinner, a spread of rice, chicken, eggplant, and big rounds of naan.

Cheryl Hudson was helping one of the Afghan kids tape a script by their front door to remind family members what to say in case they were visited by ICE agents, who cannot enter without a warrant. Hudson helped the family resettle through her Minneapolis church, Urban Refuge, four years ago. Hudson’s family and two other church friends have since grown close to the Afghans—they’ve accompanied the refugees to the emergency room and have shared many late-night dinners.

Thousands of refugees, many of them persecuted Christians, have found a safe haven in Minnesota. But for weeks now, many of them have not left their homes on advice of their lawyers and local refugee-resettlement agencies.

The Afghan family applied for green cards but are still waiting for approval, which made them worry they were at risk of arrest under the Trump administration’s Operation PARRIS, an effort announced in early January to “reexamin[e]” refugees who have been granted legal status but are awaiting their green cards.

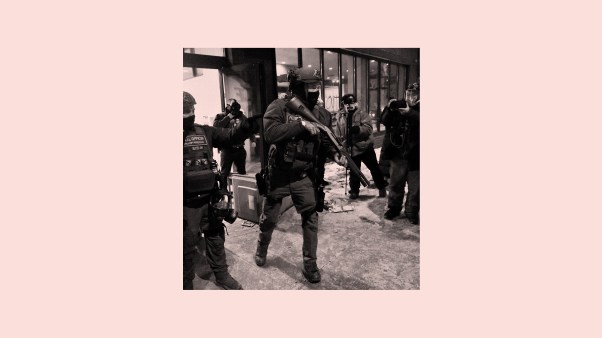

Instead of simply reinterviewing the refugees, which would be unusual on its own, federal immigration enforcement has been arresting and sending many of them to detention centers in Texas.

At least 100 refugees have been arrested in Minnesota, according to The Advocates for Human Rights, a legal aid group. The group did not know of any who had been deported to their home countries last week, but it said it could not know every situation among the more than 5,000 refugees in Minnesota potentially subject to reexamination.

“There’s been a large number of people arrested without access to an attorney or assistance, and DHS [the Department of Homeland Security] has no process or system in place to track who they are arresting or what is happening to them,” said Madeline Lohman, the group’s advocacy and outreach director, in an email to CT.

Agents did not inform refugees of what was happening to them during their arrests, according to CT interviews and lawsuits filed since.

Some refugees were released in Texas without a way to return home. Part of what immigrant churches in Minnesota have been doing in the last week is arranging travel for their refugee congregants to return home if the government releases them.

Unlike asylum, for which tens of thousands of immigrants in the United States apply even though odds of approval are low, refugee status can only be requested from abroad. Refugees must wait outside the country, often for years of vetting and background checks by multiple agencies, until they receive an invitation from the US government. They must prove that they face persecution in their home countries. They resettle in the US in partnership with an agency, often faith-based nonprofits like World Relief.

When the government first began arresting refugees a few weeks ago, World Relief’s CEO Myal Greene called it a “five-alarm fire.”

But on Wednesday night, a federal district judge issued a temporary restraining order barring further arrests and “unlawful detention” of refugees who have not been charged with any grounds for removal.

Judge John Tunheim also ordered the release within five days of all Minnesotan refugees who have been arrested. He ordered that the government return them to the state for their release and alert the refugees’ lawyers so someone can meet them, due to Minnesota’s stretch of dangerously cold weather.

A higher court could overrule the judge, and the judge could amend his own order after a fuller hearing, but refugee resettlement organizations like World Relief breathed a sigh of relief.

“Refugees have a legal right to be in the United States, a right to work, a right to live peacefully—and importantly, a right not to be subjected to the terror of being arrested and detained without warrants or cause in their homes or on their way to religious services or to buy groceries,” Tunheim noted in his ruling.

Already the arrests have shaken refugees’ sense of safety in their new country. In court filings and interviews with refugees and advocacy groups, a similar picture of ICE emerges: agents entering refugee homes without warrants and sometimes coaxing them outside through deception. A class action lawsuit recounted one plainclothes agent allegedly pretending he had hit a refugee’s car to get the refugee outside for an arrest, a tactic others shared in interviews with CT.

One refugee who was targeted at home said in the class action lawsuit that her “experience has caused her to relive similar experiences of armed men knocking on her door in the country she fled.”

US Citizenship and Immigration Services said its effort centered on “adjudicators conducting thorough background checks, reinterviews, and merit reviews of refugee claims.”

Tunheim, the federal judge, ruled Wednesday that the government could “conduct reinspections” of the refugees’ cases without arresting them.

At the Afghan family’s home, Hudson explained again why they couldn’t trust government agents or open the door for them. “I’m really sorry they’re not doing the right thing,” she told them.

But the warnings about ICE quickly gave way to happier dinner conversation. Hudson’s daughter and the Afghan kids recalled playing laser tag together and going on the flume ride at the Mall of America. Another church friend at dinner helped them refill a prescription by phone. After only four years here, some the kids in the family already have American accents and talk with the young slang of 6-7 and brain rot.

“They’ve grown in their independence greatly,” Hudson said. “We’ve grown in depth of friendship.”