When asked last month about his goals in attacking Iran, Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu stated that he sought to stop a nuclear threat. Yet he also expressed hope for a regime change.

“The decision to act,” he said, “is the decision of the Iranian people.”

Although Iranian sentiment is hard to measure, some surveys suggest widespread disillusionment with the country’s rulers. According to the nonprofit Freedom House, Iran ranks No. 20 on its list of the least-free nations in the world. But if Iranians were free to decide, on what basis would they decide what is right?

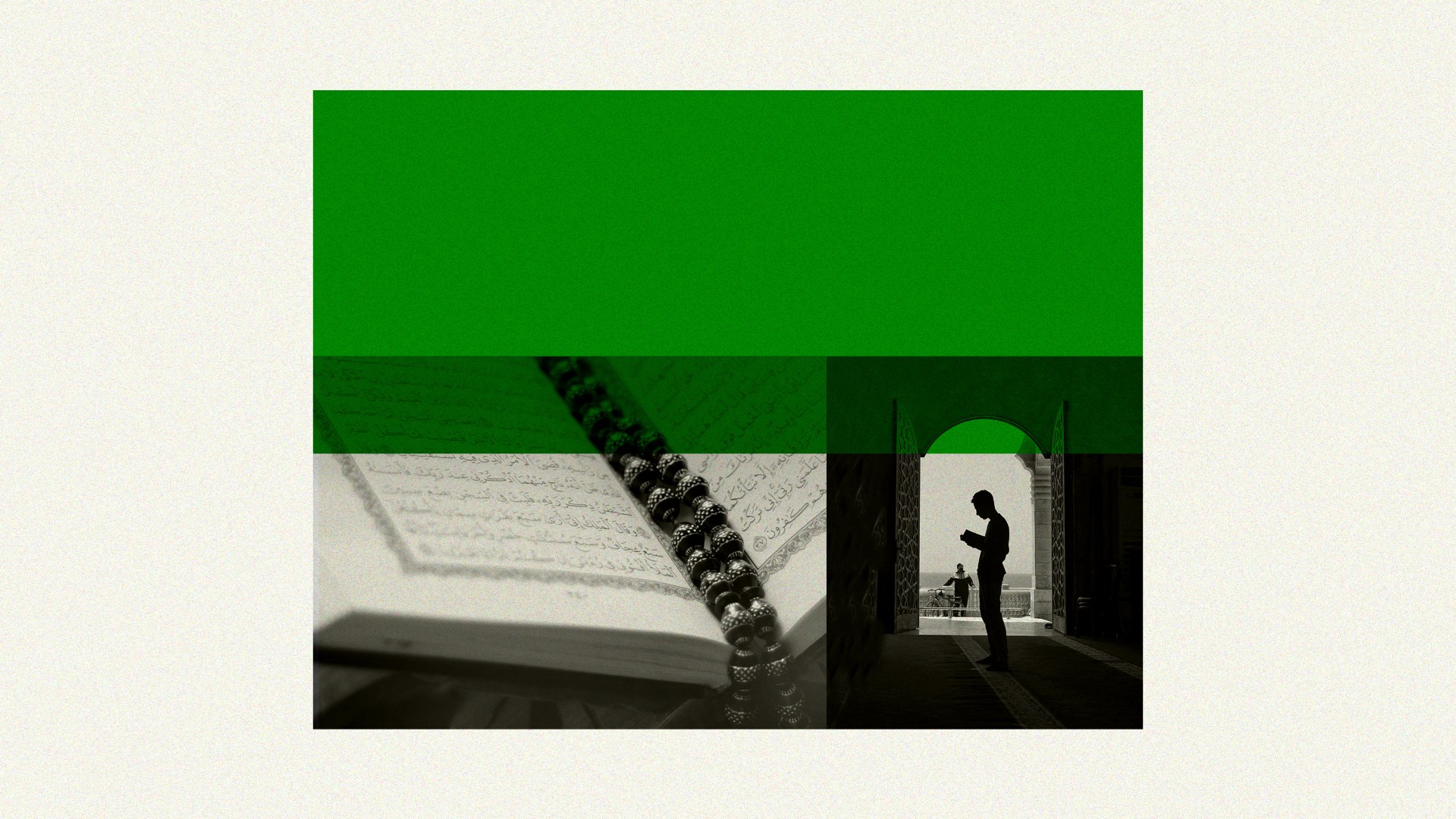

Shiite Islam offers Iranians a standard it views as just. Iran calls itself an Islamic republic. Many Iranians may appreciate the Western understanding of human rights. But long before Freedom House existed, their sect prized two concepts through which the Shiite people can judge their governments: justice and leadership.

Najam Haider, assistant professor of religion at Columbia University, calls these the core theological beliefs of Shiite Islam. Iran’s constitution purports to enshrine them via the judiciary in wilayat al-faqih, the “guardianship of the jurist.” In plain terms, the religious scholar, an expert in sharia law, is to rule and ensure fidelity to Islam. Iranians can theoretically vote politicians out of office but the chief religious scholar is in charge. He can be removed from his post—but only by fellow religious scholars.

To understand the Iranian government we need to understand Shiite political history. This article is the first in a four-part survey, based on Haider’s Shi’i Islam, Vali Nasr’s The Shia Revival, Mark Bradley’s Iran and Christianity, and interviews with Shiite experts.

Part one is the origin story, describing why Shiites view themselves as cheated out of Muslim leadership. Part two looks at how different branches within the sect responded to this loss. Although Shiite rule is historically rare, part three considers how two premodern dynasties shed light on later developments in Iran. And part four describes two Iranian personalities who played a key role in politicizing the Shiite faith.

The starting point: Politics is never far from Islam, as the Muslim prophet Muhammad also became a head of state. But for centuries, most Shiites waited for divine intervention on their behalf, and did not push to create a government themselves.

Iran is one of only four majority Shiite countries in the world—Iraq, Bahrain, and Azerbaijan are the others—but is unique as the only nation with specifically Shiite governance. The global majority Sunni population may admire Iran for its centrality of religion, its anti-Western posture, or its opposition to Israel. But Sunnis reject the theological basis of wilayat al-faqih.

This article will focus on what Shiites think. An anecdote about the highly revered Shiite hero Ali ibn Abi Talib—also admired by Sunnis—will help us understand a shared conception of justice that was so soon ruptured by politics and war.

In AD 656, Ali, Muhammad’s cousin, became the fourth caliph—successor to the prophet’s political leadership—of the rapidly expanding Muslim empire. And he had clear instructions for his governor in Egypt. Fifteen years earlier, a Muslim general conquered the Coptic Orthodox territory, the breadbasket of the Roman empire. His soldiers took up residence in garrison cities.

“Infuse your heart with mercy, love, and kindness for your subjects … either they are your brothers in religion or equals in creation,” Shiite tradition records Ali saying, “Look after the deprived who need food and shelter.”

Muslim historians say Egyptians welcomed their new rulers. Coptic historians note both liberation from discriminatory Byzantine rule and their varying treatment under Islamic governance. History is written by the winners. But over the centuries that followed, Shiite history, more often than not, came to reflect the perspectives of the Muslims who lost.

Shiites represent only 10–13 percent of Muslims worldwide, tracing their history to the losing side of a civil war that included the assassination of Ali in AD 661 after just five years as leader. After that, Sunnis controlled Islamic governance—through what is known as the caliphate—until its abolition by secular Turkey in 1924.

Iran restored Shiite political power. In 1979, the religious cleric Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini became the central figure of an Iranian revolt against the secular and Western-leaning shah. The Iranian Constitution calls this event the Islamic Revolution, though at the time it included strong liberal democratic and communist support. But the result was a kind of theocracy, which Iran then promoted through insurgent movements around the world, including Hamas in Palestine and Hezbollah in Lebanon.

Ali’s attitude about governing Egypt illustrates Shiites’ core theological belief about justice. Leaders are accountable to divinity and are to rule on behalf of the people. These principles are to characterize an institution called the imamate, the governance of a figure Shiites call the imam. In Sunni Islam, imam is a common noun that refers simply to one who leads communal prayer. It can apply also to learned scholars. Shiites invest the term with much deeper meaning.

For them, the imam is the one ideal leader of the entire Muslim community, the just and divinely guided successor to Muhammad. He is not a prophet. But he inherits the same charisma to command the allegiance of the people, and the insight to correctly interpret the Quran. Ali, Shiites believe, was the first imam—designated so by Muhammad.

The victorious Sunnis, however, view Ali as the fourth of four “righteous caliphs,” chosen not by Muhammad but by the consensus of the Muslim community. After these founding fathers of the caliphate, the institution lost its consensual character and devolved into hereditary rule.

Shiites counter by saying that tribal political ambitions prevented Ali from succeeding Muhammad immediately after the prophet’s death in AD 632. The term Shiites means “partisans” or “followers”—those who supported Ali’s claim to office. Shiite opinions vary concerning the first three to occupy the post of caliph, but polemical rhetoric can denounce these first leaders as self-seeking apostates. After Ali’s assassination, Shiites say with much Sunni agreement, that some caliphs ruled as impious autocrats.

Justice in Islam implies treating all individuals fairly according to its law, which the Quran commands Muslims to administer without partiality. Shiites say that the third caliph, however, favored his clan in the appointment of government positions. Ali reversed this policy and denounced discrimination against non-Arab converts. He redistributed wealth to the poor and refused the trappings of political power.

A non-Muslim objection is valid: Shiites have historically assigned second-class dhimmi status to Christians, Jews, and Zoroastrians—the ancient Iranian religion. Open Doors ranks Iran No. 9 on its list of countries where it is hardest to be a Christian, primarily for its treatment of converts from Islam.

But one imam defined the result of just rule as the establishment of self-sufficiency among the people. Iranian citizens of all faiths must judge if their republic qualifies—and if Iran’s vast spending on the military and foreign militias is prompted by self-defense, geopolitical ambition, or enmity against Israel. Is wilayat al-faqih the problem, they may ask, or does the world oppress true Islam?

Yet if Iran’s government falls short in this assessment, what should its Shiite citizens do? The past decades have witnessed large demonstrations against the regime. If protestors wished, they could claim a religious warrant. According to Shiite traditions, Muhammad said, “Whoever takes the right of the oppressed from the oppressor will be with me in paradise as a companion.”

The next article in this series examines how Shiites have responded to against perceived Sunni injustice.